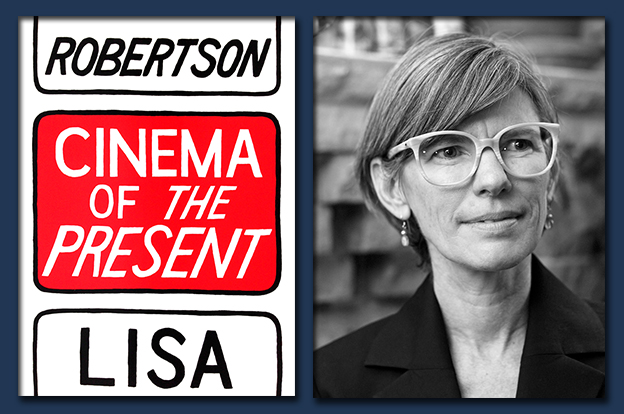

Lisa Robertson

September 13, 2019

'Prickly new cells'

Diffractive reading and writing in Juliana Spahr's 'The Transformation'

August 2, 2019

A conversation between poet-grammarians

Excerpts

November 16, 2018

'Do it like this'

November 30, 2017

Lisa Robertson on Close Listening

October 23, 2016

Moving image, moving text, never past, look in mirror (repeat)

A review of Lisa Robertson's 'Cinema of the Present'

October 8, 2015

'Outside of knowledge'

June 8, 2015

lary timewell: Two new poems

February 12, 2015

Montreal's was a desiring feminism

July 15, 2014