pedagogy

May 26, 2023

MOO for poetry pedagogy, 1994-1998

January 13, 2021

Urgent possibilities

August 17, 2020

Alternative poetries and alternative pedagogies

Joan Retallack, Kelly Writers House, 2001

May 8, 2020

Learning by doing

December 6, 2019

Sensual infrastructure

October 6, 2015

Language and pedagogy

Practical strategies for a multilingual classroom

November 21, 2014

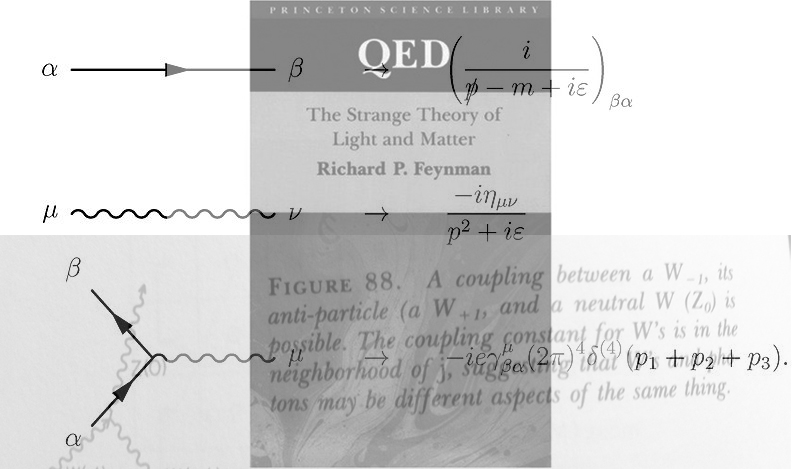

Coupling

April 28, 2014

ModPo on 'The Today Show'

December 13, 2012

ModPo overview

December 3, 2012