John Wieners's Boston haunts

For almost thirty years, John Wieners lived meagerly and humbly in the same apartment in Beacon Hill; 44 Joy Street, Suite 10 as he called it. Joy Street, originally called Belknap Lane, named after the Colonial Apothecary, Dr. John Joy, with its history of livery stables, was his home. Wieners became somewhat more reclusive in his later years, but he was still a fixture on the streets of Beacon Hill, seen often trudging tragic-comically through the streets with his bag draped around his shoulder, and a cigarette in his hand, carrying himself with a certain muted elegance. The sad fact of these last eight years is that chance sightings and encounters with the man in his world, in this world, can never happen again. Beacon Hill, a neighborhood that has changed drastically since his death, seems not to notice or to care that a great poet was ever among them or even more poignantly that he has left.

Like a ghost, Wieners can be glimpsed in the emptiness of specific places left behind. There are many places to me where I can conjure up a spark of his spirit just by walking his Beacon Hill streets.

One of the first places Wieners and I met for lunch was at the John W. McCormack Federal building cafeteria at One Ashburton Place across from the State Capitol at the top of Bowdoin Street. The cafeteria was on one of the higher floors of the building and was easy to access by elevator. In the ten years I knew Wieners, we only visited it a few times, but the memory of that lunch is very clear. I asked him if he missed Black Mountain College and North Carolina. He casually remarked, “One does not fully appreciate the landscape of a place until they have long left it.” That line has stayed with me particularly through the years. He also maintained that he once worked at the McCormack Cafeteria bussing the tables. Whether it was true or metaphoric never mattered to me. He wistfully remarked “They don’t bus these tables anymore.” There were other cafeterias where we would lunch; a state administration building in Government Center, and the Massachusetts General Hospital cafeteria to name a few.

After lunch we stood on the landing behind the McCormack building where Federal Employees stood blankly around us enjoying cigarettes in the afternoon sun. I made a comment that amused him and he casually remarked, “My cheekbones get high from you.” I told him that was such a great line I would like to use it in a poem. He dismissively changed his tone, replying “Oh, I wish I never said that.”

Once a week we would meet together to share the same routine. First, we would visit the lobby of Massachusetts General Hospital. Wieners’s cousin Walter had set up a disbursement plan for a stipend of cash to be delivered by a male nurse, Brian, who was close friends with Walter. Wieners and I would wait patiently each week in the busy lobby of MGH amidst the flow of humanity, for Brian to arrive with an envelope. Often we’d have lunch in the hospital cafeteria. A few times we would walk up the steps of the original MGH building to visit the Ether Dome.

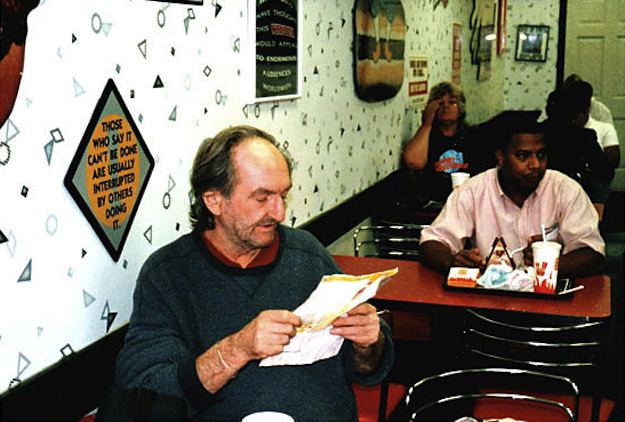

The Charles Plaza located at the bottom of Joy Street was Wieners’s lifeline to his weekly goods; cigarettes, percogesic pills, and his meager supply of weekly groceries. At that time, the Plaza had a Burger King, a CVS drugstore, a Brigham’s, and a Stop & Shop supermarket. We would walk across Blossom Street to Charles Plaza to have lunch at the Burger King. Wieners would always order the same thing — a plain hamburger, french fries and a coke. On the hamburger he would put nothing except multiple packets of salt. We’d sit down to a fine Burger King meal amidst the lunchtime crowd of Beacon Hill. Once, a publisher and admirer of Wieners planned on meeting him for lunch. The publisher showed up on Joy Street with a single rose as a gift and offered to take Wieners anywhere in the city for lunch. He suggested Harvard Gardens. Harvard Gardens, which figured prominently in Wieners’s poem “Chophouse Memories,” where he sat reading poetry in the humid summer evening of Beacon Hill, as Frank O’Hara and Jack Spicer wept in the “incipient rain and electric-charged air.” It has been a Beacon Hill institution for over forty years. Wieners had gone there many times throughout the years, but he never went there in the time I knew him. Wieners thought about the publisher’s offer for a moment and deferred making a decision until we crossed over Cambridge Street. Wieners suggested since we were so close to Charles Plaza we should just go to Burger King. The publisher was deflated. He insistently reiterated his intention to buy lunch anywhere Wieners desired in the city. I knew where we were going from the moment we stepped out onto the street. The three of us sat in the Burger King. The publisher was baffled and mortified that his date with Wieners’s was less than he dreamed it would be. I sat there next to Wieners, the awkward third wheel of the date. Wieners presided over the impaired proceedings, answering questions courteously, completely content to be exactly where he was.

We’d also visit the CVS pharmacy for three specific items that were more important to him than sustenance. He would pick up, religiously every week, a pack of Kool cigarettes, a box of Percogesic pills, and a Primatene Mist inhaler. The Percogesic pills were over-the-counter pain relievers. For some reason Wieners had to have a refill of that specific brand every week. The Primatene Mist inhaler helped him breathe but it probably gave him a kick as well. He would stand outside the drugstore with a cigarette in one hand and the Primatene Mist inhaler in the other. After each drag on his cigarette, he’d immediately take two puffs on the inhaler, which would always make me laugh. “They kind of cancel each other out, don’t they?” I asked him. “No, not all.” was his curt response. If the store was out of Percogesic pills or Primatene Mist, we would walk down Cambridge Street to the “Phillips” as John called it. It was another CVS pharmacy on Charles Circle across from the Old Charles Street Prison. Before it was a CVS it was a local independent drugstore and Wieners continued to refer to it by its former name. The Phillips CVS, in particular, played a vital role in Wieners being properly identified after his death. Wieners had no identification on him when he suffered his debilitating stroke in the Blossom Street parking lot located right behind the hospital. What he did have in his pocket was a receipt for his weekly purchases. Through the dogged pursuit of a social worker at the hospital, she was able to trace Wieners CVS savings card number on the receipt back to his apartment, and ultimately to his cousin Walter, whose name was on Wieners’s apartment lease. Luckily, his family and friends were notified just in time to say goodbye before he passed away. But, not before he laid unidentified for five days in the intensive care unit in a coma, assumed indigent and homeless by the hospital staff.

Just around the corner from the Phillips CVS, is the Phillips playground. Along with the Myrtle Street Playground, this was Wieners’s favorite place to stop off and enjoy a cigarette. Phillips playground is a two level playground on the north slope of the Hill surrounded by a metal fence, somewhat hidden between buildings. Wieners would sit on the bench with his head cocked, smoke slowly escaping his lips as Beacon Hill nannies ushered children to the lower level structure. We’d sit in silence for thirty minutes or more sometimes until I’d have to make the move and break the spell. Close to the Myrtle Street playground, Rollins Place was another secret location John liked to duck into for a smoke and some afternoon meditation. Rollins Place is one of the most interesting courtyards in Beacon Hill. It is a hidden cul-de-sac with a garden and paved courtyard consisting of six single-family townhouses with a unique faux Greek Style white mansion at the end of the alley. Wieners loved to linger in the cool shadows of the courtyard on a summer day.

Wieners favorite window in the back room of his apartment overlooked the rooftop of the African Meeting House, located on a dead end off Joy Street called Smith Court. This street had been the epicenter of Black culture in the 1800s. Wieners knew well the secret alley behind the Meeting House that lead up the hill and out onto Russell Street. The alley was rumored to have been part of the Underground Railroad during the Civil War. Nearby, Wieners participated in Steve Jonas’s poetry magic evenings in the sixties with poets Joe Dunn, Carol Weston, Rafael Gruttola, and others.

Down the hill on Joy Street towards Cambridge Street is 78 Joy Street, the home for many years of poet and Wieners supporter Jack Powers. Wieners would rely heavily on Jack’s good graces throughout his life on Beacon Hill. Jack would always feed Wieners or give him smoke money while persuading Wieners to read at some Powers sponsored reading in return. Jack was a conduit for reunions with old friends such as Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, Ed Sanders, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Herbert Huncke; when they were in town. Powers also worked tirelessly to book paid readings for Wieners, often paying him out of his own pocket. Powers was a lifeline for Wieners on the Hill. It was through Jack that I first got to know Wieners.

A particular venue for many Wieners readings in the nineties was the Old West Church on Cambridge Street. The historic church dates back to the Revolutionary War and is where the phrase “no taxation without representation” was first coined. Sadly, many of Wieners’s readings there were sparsely attended but he would always read diligently whether there were ten people or 100 people present, some readings much more compelling than others.

Another notable church in Wieners lore is the Charles Street Meeting House on 73 Charles Street. The church was known in pre–Civil War times as a stronghold of the anti-slavery movement where Frederick Douglas, William Lloyd Garrison and Harriet Tubman gave fiery speeches. In 1953, during Hurricane Hazel, Wieners happened upon a reading by Charles Olson at the Meeting House where he was so taken with Olson’s reading he soon followed Olson to Black Mountain College. The modern day Meeting House is a disappointment to those who go there to see the church where this historic reading took place. The church was sold in 1979 and was renovated into a flower shop on the first floor and office space on the upper floor. It stands next to the firehouse made famous in the TV series, Spencer for Hire. Wieners and I visited the Meetinghouse only once, standing at the elevator bank momentarily then we were gone.

Driving through Boston I’d often catch a glimpse of Wieners in front of the Boston Public Library. As I got to know Wieners, I realized why I’d always see him outside the library. The Glad Day bookstore was a long-standing gay bookstore right across the street from the BPL. Whenever Wieners would get paid by check for a reading or for residuals from a publisher, he’s go to the Glad Day to get his checks cashed. The owner of the Glad Day, John Mitzel, was an old friend of Wieners who would always front Wieners money without any expectation of restitution.

Once, while driving Wieners back from the Glad Day bookstore en route to the supermarket, we averted a near tragedy on Bowdoin Street; right next to the State Capitol and the McCormack Building. As we drove down the Hill, I signaled to proceed to the right to grab an open parking spot. As I cruised over to the spot, I heard a crash and saw a biker come hurtling over the hood of my VW. Wieners put his hand over his mouth and let out an “Ooooh.” I maintained my cool and got out to see if the biker was all right. The biker was laid out in front of the car, sprawled on the street. I asked him if he was hurt and if he needed an ambulance. He cursed and told me to turn around and put my hands on the car. I first thought he was a bike messenger but then noticed his blue shorts and shirt and realized that I had hit a Boston Police Officer on bike patrol. Wieners and I sat in the car as three cop cars came and went. Each cop glared at us with angry disgust. After waiting nearly an hour I asked the officer if they could at least let Wieners go. They reluctantly released him when they realized he would not be a reliable witness. He draped his bag around his shoulder, took his rubber band from his ponytail, put it around his wrist, and went ambling down the hill to the Stop & Shop. After two hours of being held and questioned, I was finally, miraculously let go without even a ticket. I caught up to Wieners at the Stop & Shop, pushing his cart down the aisle as if nothing happened.

The one time we actually went inside the Boston Public Library together was to see the original version of A Star Is Born. We sat in the darkened basement of the BPL watching James Mason and Judy Garland. Wieners was rapt and attentive during the entire movie. I was less so. I dozed off several times during the movie, once even jarring myself awake from my own snoring. As we walked out, I felt like Peter in the Garden of Gethsemane. I half apologized for going catatonic during a movie that obviously meant a lot to him. “That’s alright” he said, “Jimmy Mason makes you groggy.”

There are a few places I never visited with Wieners although I tried to persuade him to go with me. The first place was the Boston Athenaeum. I was a member in the late 1990s and I thought he would enjoy going back there since he had told me stories of going there years prior. I often tried to cajole and persuade him into going to the Athenaeum with me. He would initially agree and then subtly his enthusiasm would dissipate until he was resolute in his decision not to go. In fact, I rarely ever saw Wieners on the Robert Lowell/General Hooker/Boston Brahmin/Boston Common south slope side of Beacon Hill unless we were driving through the neighborhood.

I also tried to get him to visit the Common Fountain with me, since his “Ode to a Common Fountain” was among my favorite poems of his. But I couldn’t even get him to stroll the Common with me, let alone get him to stand before the great fountain of his youthful dreams. The other place that he was interested in visiting with me was Saint Anthony’s Catholic Church off Summer Street near Downtown Crossing. I worked near the church and we had made grand plans to attend the Sunday Service but we were not able to make it happen, for whatever reason. Sadly, the only time Wieners and I were in church together was at Saint Gregory’s in Dorchester at his funeral, which was more poignant and touching than I could have imagined.

I am often referred to as Wieners informal caregiver in the later years of his life. The truth is I gave him no more care than any friend would have. If anything, he showed as much or even greater care for me than I for him. Robert Creeley echoed this feeling: “We are not taking care of John any more than he is taking care of us, if you hear me. We need him very much. We need what his poems can say.” Towards the end of his life, his world and the neighborhood he lived in became a place where it was increasingly harder for Wieners to have an independent life on his own terms, given the challenges of mental illness and poverty he had to manage every day. Beacon Hill is no longer a place where a poet such as Wieners can live independently. Every time I walk the streets of his neighborhood, I am reminded of him, and of his generosity, his grace, his indomitable spirit, and his love for his hometown of Boston. Although we no longer have Wieners, we have his poems. His voice echoes and his spirit remains alive to me in the streets that ribbon behind the state capitol on the bohemian side of Beacon Hill, where so much has changed.