A constellation of transnational poetics

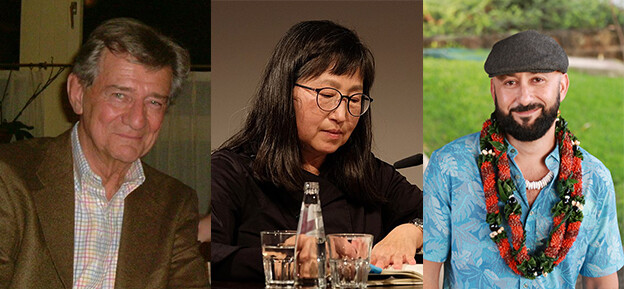

From Deleuze and Guattari’s essay on “Minor Literature” to Alfred Arteaga’s work on Chicanx poetics, theorists have studied the relationship between power and language, describing how creative writers find inventive ways to interrogate monolingual and nationalist logics.[1] Often, personal as well as historical conditions shape an author’s linguistic choices. My interest here lies in how poets use citation and translation as craft techniques in forging poetic languages that challenge powerful configurations and histories. In this essay, I analyze how works by Don Mee Choi, Craig Santos Perez, and Gerald Vizenor offer a constellation of transnational poetics that unsettles (neo)colonial histories and territorialities. The emphasis I place on citation and translation as craft techniques aims to acknowledge the particularity of each poet’s work, and to showcase how placing these poetries in conversation fleshes out questions related to the hegemony of English as well as the possibility of its deployment in a decolonial poetic.

In this transnational constellation, the United States emerges fused with militarization, as an occupying force in three interrelated territories on Turtle Island, in the Pacific, and in Asia. If, as Donald Pease notes in Reframing the Transnational Turn in American Studies, the transnational “names an undecidable economic, political, or social formation that is neither in nor out of the nation-state” then the transnational emerges in the shifting terms and promises of the undecidability which accompanies each poet’s dismantling of normalized (neo)colonial narratives and the location of the English language in relation to (neo)colonialism.[2] Each poet’s purpose does not end at a critique of hegemony, but rather opens up undecidability as a site of decolonial agency.

To further elucidate the shape of this transnational constellation, it might be clarifying to establish a relationship between undecidability and Walter Benjamin’s conceptualization of historical citation as a liberatory moment. Both Rudiger Kunow and Azade Seyhan have offered connections between Benjamin’s concept of citation and transnational poetics. In Writing Outside the Nation, Seyhan discusses Benjamin’s theorization of the promise of memory, which as it surfaces at a “moment of danger” allows for the relevance of the emancipatory in history to emerge.[3] In such a moment, Seyhan notes, memory “translates the ciphers of the past into alphabets of the present and makes history readable.”[4] This figurative work of citation — as a tool of liberatory translation — emerges across the work of the three poets. As for Kunow, he describes citation as a literal tool that effects interruption and disruption in the literary text, one that is “both located and moveable, sedentary and open to employments at other sites.”[5] He thus links citation to the transnational as an encounter, one that privileges the situated “meeting” of cultures over a figurative “mixing.” My own understanding and use of citation as a reading heuristic here is informed by the historical and figurative significations described by Seyhan and Kunow, and by citations’ relationship to language(s) and translation.

Readers may glimpse multiple strategies at play in the juxtaposition of Vizenor’s, Choi’s, and Perez’s creative uses of poetic language(s). Vizenor’s epic novel in verse uses citation and translation to offer a whole narrative, working to dislodge the English language from its colonial logics and to reterritorialize it within Indigenous discourses. Perez’s multibook project, on the other hand, is recursive and open-ended in shape as it investigates processes of loss and recovery — linguistic, cultural, and environmental — in relation to history and (de)colonization. Perez “makes history readable” by gathering surviving fragments to trace stories. Working with fluency in English and Korean, Choi creates various textures, using storytelling and fragmentary juxtaposition and collage, to intervene in historical narratives. Her poetry insists on the disruptive potential of citation and defamiliarizes poetry’s association with beauty.

The question of language’s relationship to power is another aspect of the transnational constellation that emerges in discussing these three poets in proximity. The craft techniques the poets use emerge from the particular project they engage and the (trans)national and historical contexts from which they write. For instance, Vizenor’s epic narrative effectively indigenizes English as a poetic language. Don Mee Choi, on the other hand, interrogates the links between geopolitics and monolingual culture. Out of the three, Perez most directly takes up language as subject and instrument, as he explores the historical loss and transformation of Chamorro language and culture in successive Spanish, Japanese, and United Statesian colonial occupations.

Sovereign narrative, natural reason in Bear Island: The War at Sugar Point

Gerald Vizenor’s Bear Island: The War at Sugar Point is an epic narration of the last armed confrontation between the United States military and the Anishinaabe, in which settler historical narratives are overcome and decentered. The United States’ official history usually elides the war at Sugar Point from its historical narrative, highlighting the massacre at Wounded Knee as the final “representative” contact between Native Americans and the settler colonial state. Vizenor’s Bear Island reenacts the victorious battle between nineteen Anishinaabe Pillager warriors and seventy-plus immigrant soldiers, countering settler narratives that relegate Native nations to victimization. The lyric language of Vizenor’s epic arises from a polyvocality embedded in “survivance [as] the continuance of stories.”[6] Vizenor’s own experience as an officer in the United States military during the occupation of Japan, formative of his interest in haiku, also appears in the form of this verse novel, which I refer to as “haiku-adjacent.”

Bear Island’s citational poetic is threaded into the epic’s narrative. In the chapter titled “Bagwana: The Pillagers of Liberty,” Vizenor introduces readers to the Pillager warriors; to Bagwana, the sole survivor of a battle between the Pillagers and the Dakota; and to Anishinaabe leaders such as Chief Flat Mouth and Keeshkemun (Sharpened Stone). Various historical events, including a battle between the Anishinaabe Pillagers and the Dakota, the settler militia’s “frontier treachery” at Sand Creek, and the weaponization of smallpox, are mentioned to better contextualize the War at Sugar Point.[7] The epic is thus introduced as an Indigenous telling embedded in intersecting tribal histories and in intertribal relations.

Kimberly Blaeser notes that Bear Island performs aspects of the epic and the lyric, and that “Vizenor, writing in his own liberated genre, in two languages, linking mythic, historic, and cyclical time, performs on the page a telling that means to invite or effect change in the world off the page, for contemporary readers/listeners.”[8] Organized linearly in six chapters, the book takes readers from an introduction to Bear Island and the Anishinaabe band of Pillagers in the first two chapters, to Bugonaygeshig’s story which marked the war’s occasion, and then to three chapters each dedicated to a specific day of the war between October 5, 1898, and October 9, 1898. Bugonaygeshig, an elder medicine man and Pillager Chief, is central to the events. He was arrested by federal agents over false whiskey charges, and when released, walked one hundred miles to his home at Bear Island. The police’s second attempt to arrest him prompted Anishinaabe men and women to his defense. The army’s Third Infantry was then dispatched to Bear Island. Despite the serial arrangement of events in book chapters, the imagistic and polyvocal telling within each of the chapters utilizes refrains in a citational and bilingual poetics that creates the cyclical aspect that Blaeser describes.

The condensed form of Vizenor’s poetry, employing variations between three to seven syllables in a line, resonates with the Haiku form. In “In the Envoy to Haiku,” Vizenor discusses his encounter with Japanese literature during his time serving in the military. He writes:

[the] presence of haiku, more than other literature, touched my imagination and brought me closer to a sense of tribal consciousness. I was liberated from the treacherous manners of missionaries, classical warrants, the themes of savagism and civilization, and the arrogance of academic discoveries. The impermanence of natural reason and remembrance was close to the mood of impermanence in haiku and other literature.[9]

One might read Bear Island’s shape and rhythms as transcultural in the sense that Vizenor writes a landscape akin to haiku’s “concise concentration of motion, memories, and sensations of the seasons without closure or silence.”[10] For instance, one can observe this attention to motion in Vizenor’s first chapter, “Overture: Manidoo Creations”:

october storms

turn and rush

across leech lake

great waves

break on shore

at bear island

native colors heave

elusive otters

trace the bay

ravens bounce

on the main

and wolves await

the sacred rise

of sandhill cranes

over the birch

feathers and praise

at sunrise[11]

Dissolving the boundary between image and event, Vizenor depicts the movements and positions of the inhabitants of the landscape, animating the lake and land. Such imagistic technique evokes both haiku and what Vizenor has called “natural reason.” In “Aesthetics of Survivance,” Vizenor describes natural reason in resistance to and distinction from the monotheistic “godly reason” that regards the “natural” through the lenses of domination and romanticization. Natural reason exists beyond the binaries of colonial thought, a recognition of agencies that extend beyond the human.[12] He writes,

Native stories of survivance are prompted by natural reason, by a consciousness and sense of incontestable presence that arises from experiences in the natural world, by the turn of the seasons, by sudden storms, by migration of cranes, by the ventures of tender lady’s slippers, by chance of moths overnight, by unruly mosquitoes, and by the favor of spirits in the water, rimy sumac, wild rice, thunder in the ice, bear, beaver, and faces in the stone.”[13]

Vizenor’s bilingual poetics and turns of translation also help create his sovereign transnational aesthetic. Vizenor juxtaposes conflict with mediation in a translation that refuses to follow unidirectionality in Bear Island. At one level, this occurs by variations in the ordering of Ojibwe and English, as English follows or precedes Ojibwe names and words. In “Bagwana: The Pillagers of Liberty,” Vizenor mentions the translation of Bagwana’s name, writing,

solitary spirits

marvelous sentiments

of shamans

court and tradition

under the cedar

set by names

ravens and bears

visual memories

traces of bagwana

turned in translation

by my heart

a native warrior

and natural presence

at the tree line[14]

This initial siting of Bagwana — a conjuring of the storyteller’s survival tales in the Dakota-Pillager battle — is diffused and associated with cedar and ravens and bears. Bagwana’s translated name, “by my heart,” is evoked repetitively, appearing after this initial mention in four chapters, all except the first, “Manidoo Creations,” and the last, “War: Necklace: 9 October 1898.” Generally, Vizenor’s translation acts appear as an interruption of semantic meaning, inducing a poetic effect and creating the cyclicality that Blaeser notes. Translation thus effects mediation at the scale of the book as well as at the scale of the stanza and the word. Vizenor overturns linguistic and semantic hegemony by relocating English and Ojibwe words within Native discourse. Such a poetic effect could be understood as a gesture of Indigenizing the English language.

In the last chapter of Bear Island, Vizenor lists the sacred objects and possessions the surviving officers have stolen from the Pillagers as well as the losses of the settler army. Moreover, Vizenor lists the names of the immigrant soldiers, tracing where they came from, the countries in which they battled, and the wounds they sustained or whether they have been killed. By reintroducing the trajectories of the soldiers, Vizenor destabilizes their singular and undifferentiated identification as the settler state’s agents and their identity as American citizens. And by revealing the army’s plundering, Vizenor demonstrates the settler and imperialist logics responsible for the soldiers’ “crippled / mind and body / by military conceit.”[15] Militarism is revealed as constitutive of the United States as a settler colonial occupier in Turtle Island and an imperial presence elsewhere. For as Jace Weaver notes in his introduction, it is this same Third Infantry of the army which “secured the United States’ Manifest Destiny” and extended its imperial and colonial violence to Asia, the Pacific, and the Caribbean shortly after the Indian Wars and, a century later, to Iraq.[16]

Vizenor’s citational poetic creates an Anishinaabe discourse in a decolonized English. His narrative, a whole story that moves both cyclically and linearly, stretches what Benjamin identifies as a “liberatory moment” to translate Native sovereignty into the present, interrupting settler territoriality and History. The implications of resituating the War at Sugar Point in relation to transnational Indigeneity and against tragic history carries the promise of repetition, of sustaining decolonial readings of the past and envisioning future action.

Anti-neocolonial citation in Don Mee Choi’s work

Don Mee Choi employs a range of intertextual techniques in her oeuvre. In Petite Manifesto, she creates visually seamless prose poems that assimilate multiple texts and voices. Whereas in a video of a translated poem series such as “Twin Flower, Master, Emily,” she appropriates voices as personae within the epistolary form. And in Hardly War, Choi visually preserves the distinct edges and textures of languages, texts, forms, and media arranged and assembled to retell the history of war and imperialism in Asia. The presumption of a single, monolingual speaker is an insufficient reading heuristic in encountering Choi’s poetry. For her emphasis on polyvocality and citation is embedded in an understanding of the incommensurability of narratives as well as the violence of displacement. In an interview with the Lantern Review,Choi says: “[w]hen I use another text in my writing I am also displacing it to see how wrong it could be and to see if any new connections can be made in its new geography. In ‘Twin Flower, Master, Emily,’ I displaced Dickinson’s lines. Emily got dispatched to the DMZ of the Korean peninsular [sic].”[17]

Choi’s serious play with citation discloses how language, migratory as it could be, relies on and drags in and leaves behind contexts that exceed its homely meaning. To dispatch Dickinson to the DMZ is not only a gesture that disrupts readers’ understanding of a “correct” cultural literary location, but it is also an anachronistic gesture that activates multiply located memories and layers geographical histories. Indeed, in Choi’s work, the United States emerges as an imperialist force in Asia. In her pamphlet Translation is a Mode = Translation is an Anti-neocolonial Mode, Choi writes, “I come from a land where we are taught that the US saved us from Commies and that North Korea is our enemy. I come from a land of neocolonial fratricide. I come from such twoness.”[18] Serving as a translator of feminist Korean poetry and tracing the history of Korea from the Japanese occupation to its status as a neocolony of the United States in her own poetry, Choi engages “anti-neocolonial translation” in ways that acknowledge, also, gender’s entanglements in history.

Choi’s citational poetics embrace fragmentation and lacunae, eschewing the seamless lyric vocality of national(ist) discourse. Beyond the translocation of meaning implicated in citational transfer and intertextual layering that Choi characterizes as “wrong,” she stretches “wrongness” to encompass language and translation. For instance, she notes how her English is considered wrong and how translation “is in a perpetual state of being wrong because it isn’t the original. But as you can see, not all originals are considered perfect. Some originals are plain wrong to begin with.”[19] Revealing the layers of estrangement or exclusion ascribed to people, cultures, and languages within empire’s logic, Choi’s embrace of the “wrongness” attached to an Asian English or the Korean language within a hegemonic monolingual culture speaks not only to the limits of “mixing” — conjured as constitutive of the benevolent multicultural empire — but also of Choi’s refusal of an assimilation dependent on historical erasure.

In Hardly War, Choi deploys citation as a tool for reconfiguring normative aesthetics. She disrupts the association of natural landscape with beauty. Instead, Hardly War reveals how landscape is regarded from the militaristic lens of establishing territorial hegemony. Arranging excerpts from her father’s war photography, military statistics, news stories, and verse in proximity, Choi suggests correspondences between Korean and Japanese wooden architecture and United States firebombs. In such arrangement, a “purely” cultural and necessarily ahistorical aesthetic of the pastoral cannot hold as separate from territorial domination and scorched earth policy. Moving between the Japanese occupation, Korean War, and Vietnam War, Choi by precise arrangements and recovered fragments renarrates South Korea’s history. She writes, “I am trying to imagine race=nation, its language, its wars. I am trying to fold race into geopolitics and geopolitics into poetry. Hence, geopolitical poetics. It involves disobeying history, severing its ties to power.”[20] Hardly War tethers, juxtaposes, and returns materials and events to create a multilayered witness to gendered geopolitical violence.

Especially striking, perhaps, is how in Petite Manifesto, Choi creates an order to the “transparency” of her intertextuality.[21] She appropriates Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver Travels, Gertrude Stein’s The World is Round, questions from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, and other texts, mentioning sources at the end of each poem. She also uses epigraphs: one from Aimé Césaire and one from Roberto Bolaño. In the body of the poems, Choi references the works of various Korean authors whom she mentions in the Notes page at the end of the chapbook, including Korean author Chungmoo Choi in Dangerous Women: Gender and Korean Nationalism; Saewoomtuh, a grassroots South Korean organization advocating for women exploited by military prostitution; and Choi’s own translations of literary pieces by writers Ch’oe In-ho and Pak Wan-so. Her citational order suggests that these poems speak by reworking colonial languages of art and culture, theory, and official administration; that they speak from the heart of decolonial feminism and Korean literature; and are positioned in relation to Caribbean and Latin American voices. This citational order intervenes in discursive power structures, emphasizing global decoloniality as a frame in which one may engage the poetry.

Indeed, the difficulty of Choi’s citational and bilingual poetic lies in the care with which she opens up history to scrutiny by rewiring English as a literary language. Her texts bring forth the disturbing familiarity of sanitized discourses as a means to highlight the ruptures of history, to home in on the lived violence and traumas seamless “master” narratives hide.

Language of water: Craig Santos Perez’s from Unincorporated Territory

In Craig Santoz Perez’s multibook project from Unincorporated Territory, Guam emerges against its paradoxical status as an “unincorporated territory” of the United States and its “strategic” position in regards to militarism. The fact that Guam’s inhabitants have a truncated United States citizenship that denies them rights of self-governance as well as full participation in civic life demonstrates the empire’s opportunistic deployment of the discontinuity of the supposedly natural ties between borders, territoriality, and governance. In the first book of the series, from Unincorporated Territory [Hacha], Perez contextualizes his work in relation to Guam’s history of successive colonizations and invasions by Spain, the United States, and Japan, which Perez calls a “redúccion” due to the “cultural, political, geographic, and linguistic” erasures accruing over centuries.”[22] As Perez’s recuperation of language, history, and stories reckons with layers of loss, from Unincorporated Territory takes on a complex poetic shape that develops from one book to another in the series. Paul Lai notes that Perez “densely weaves text in ways that rely on outside contexts for meaning. The reader must become a detective, tracing flows of meaning from the words on the page to other pages in the book as well as web sites on the Internet.”[23] Indeed, the project’s structure emphasizes recursive reading as constitutive of the layered and complex temporality of a decolonial poetics.

In an interview with the Lantern Review, Perez says: “I employ trans-book threading in my own work as poems change and continue across books (for example, excerpts from the poems “from tidelands” and “from aerial roots” appear in both my first and second books).”[24] By this trans-book threading, Perez weaves decolonial gestures, visions, and strategies toward cultural recuperation. For instance, across from Unincorporated Territory, Perez investigates the ecological impacts of colonization and militarization through the narratives of the brown tree snake, a species introduced to Guam’s ecology by the United States military. He writes, “During and after the war, the Allies controlled the Marianas, a primary base in the Pacific. The US military shipped equipment and salvaged war material to permanent bases and scrap metal processors on Guam. The first brown tree snakes reached the war-torn island as cargo ship stowaways.”[25] In Hacha, Perez links the death of “cousin renee” to the introduction of the brown tree snake in the larger context of plans to transfer eight thousand marines and their dependents to Guam from Okinawa. from Unincorporated Territory: [Saina], the second book of the series, juxtaposes the unhampered access of militarism and tourism to Guam with the conditionalities that accompany (im)migration and asylum seeking to the United States. And in the third book, from Unincorporated Territory: [Guma’], Perez shifts his focus from the snakes to the Micronesian kingfisher (sihek), a species of birds that almost went extinct in Guam due to the predation of the brown tree snake. Perez’s narrative of how mainland zoos recaptured the remaining siheks to breed them in California and elsewhere anticipates the amnesia of how the birds went extinct in the first place, an erasure of the fact that ecological disaster is brought on by militarization.

Language in from Unincorporated Territory is both subject and instrument as Perez charts cultural-linguistic loss, traces how a word’s meanings were altered, and recuperates Indigenous knowledge. In Hacha, Chamorro, Spanish, Japanese, and English words all appear in the poems, wresting the reading process from linearity. The delayed understanding of the word by the non-Chamorro-speaking reader creates an interruption between the word’s meaning and its spatial position on the page, which has an effect of simultaneous dislocation and translingual weaving. In the podcast series Cross Cultural Poetics, Perez discusses his family’s response to reading his book, gesturing to the variable and disrupted relations between the visuality of words and sounding of language for Chamorro speakers as well.

One poetic thread that Perez engages is naming practices. Naming appears as a colonial imposition, a claim to ownership over places and peoples in from Unincorporated Territory: [Hacha]. The first poem series, titled “from LISIENSAN GA‘LAGO,” which references the tags the Japanese occupying forces forced Guam’s people to wear, lists the names given to Guam and the Micronesian Islands by several outsiders, including Magellan, lost on his way to the Philippines; San Vitores, who sought to spread Christianity to Chamorros and established the first Catholic church in Guahan; and Otto Van Kotzebue, a Russian explorer.[26] The colonial encounter is shaped by renaming as means to consolidate a sense of possession in language.

In the following book, from Unincorporated Territory: [Saina], readers glimpse a conceptual departure from the deconstruction of colonial maps in Hacha to Perez’s increased attention to Indigenous histories via figurative and literal vessels. By linking ancestral stories and the reconstruction of the Chamorro ship, the “flying proa,” Perez navigates cultural loss and recovery. Examining the painful incommensurability between poetic fluidity and linguistic “redúccion,” and informed by the work of anthropologist Epeli Hau‘ofa, who calls for reinserting the sky and the ocean into the universe of Pacific area studies, Perez heightens his approach to water. Consider, for instance, how the Chamorro language is figured as “a lost ocean” within the hegemony of English:

i say “saina” and i know i am not between two languages—not between fluency

and fluency—not a simple switch—i say “saina”—heat along converging diverg-

ing linguistic boundaries—i write “saina”—seamount, island—within torrents of

english—i am not between two languages—one language controls me and the

other is a lost ocean—wavelength, wavebreak—not code.[27]

The bi- and interlingual shape of the poems also transforms across the series. from Unincorporated Territory: [Hacha]’s legend structure (a visual-linguistic cartography) of translation, some of which recurs in in from Unincorporated Territory: [Saina], disappears in the third book of the series. Chamorro words rub against “the ocean of English” more directly, with less “excerpting.” And as the ocean and water become increasingly pivotal in from Unincorporated Territory: [Guma’], Perez repeats a variation of the invocation “because [our] lungs are ninety percent water.”[28] Water’s centrality creates a web of reterritorializing relations between sovereign ocean and human body.

from Unincorporated Territory’s arrangements arise necessarily from the complexity of Guam’s history and Perez’s decolonial project. Out of the three poets whose works I discuss, Perez most directly takes up language as subject and instrument, exploring the historical transformations of Chamorro language and culture. By retelling Guam’s history, tending to cultural recovery, and waging critique in the present, Perez’s citational poetic emphasizes interpretation and discursive intervention as liberatory practices.

Undecidability: a transnational constellation

When poets privilege undecidability against the grain of colonial logics, citation opens up a transnational “interruption to the status quo.”[29] Undecidability in Vizenor’s work emerges in narrating a battle that disobeys — by virtue of the Anishinaabe’s military victory — Native erasure and victimization. The implications of resituating the War at Sugar Point in relation to transnational Indigeneity and against tragic history carries the promise of repetition, of sustaining decolonial readings of the past and envisioning future action. In Craig Santos Perez’s work, paradoxes of Guam’s unincorporated status offer an example of a congealed undecidability, one that the United States opportunistically deploys to extend militarization and undermine Chamorro sovereignty. Yet, Perez’s work overturns the tenets of colonial hegemony to reconfigure undecidability in the anticlosural shape of the project. He works from within history to recover Chamorro stories, practices, and vessels. Finally, Don Mee Choi’s work juxtaposes multiple forms, media, and languages as a way of critiquing the embodied violence of imperial encounters and colonial boundary-making. Her work deploys citational practices to expose gendered geopolitical violence. Therefore, hers is a witness and declaration against the stability and certainty of neocolonial discourses. Promise of the liberatory lies in the fissures that Choi introduces to “master” narratives, and undecidability emerges in her feminist refusal of the terms of nation-state and empire.

Acknowledgement: my gratitude to Kumkum Sangari, Brenda Cárdenas, and Kimberly Blaeser, who generously engaged with the first draft of this article. My thanks also to Jacket2 for their editorial feedback. Part of the the discussion of Vizenor's work appeared in an article written in Arabic and published by 7iber.

1. See Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, “What is Minor Literature?,” in Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature, trans. Dana Polan(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 16–27; and Alfred Arteaga, Chicano Poetics: Heterotexts and Hybridities (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

2. Winfried Fluck, Donald E. Pease, and John Carlos Rowe, eds., Re-Framing the Transnational Turn in American Studies (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2011), 5 (my emphasis).

3. Azade Seyhan, Writing Outside the Nation (Princeton, NJ: University of Princeton Press, 2001), 34–35.

4. Seyhan, Writing Outside the Nation, 35.

5. Seyhan, Writing Outside the Nation, 253.

6. Gerald Robert Vizenor, ed., Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 1.

7. Gerald Robert Vizenor, Bear Island: The War at Sugar Point (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 31.

8. Kimberly Blaeser, “The Language of Borders, The Borders of Language,” in The Poetry and Poetics of Gerald Vizenor, ed. Deborah L. Madsen (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2012), 16.

9. Gerald Robert Vizenor, “The Envoy to Haiku,” Chicago Review 39, no. 3/4 (1993): 57.

10. Vizenor, “The Envoy to Haiku,” 58.

16. Vizenor, Bear Island, i–xiii

17. Don Mee Choi, “A Conversation with Don Mee Choi,” The Lantern Review, December 5, 2012.

18. Don Mee Choi, Translation is a Mode = Translation is an Anti-neocolonial Mode (New York: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020), 1.

19. Choi, “A Conversation with Don Mee Choi.”

20. Don Mee Choi, Hardly War (Seattle, WA: Wave Books, 2016), 4.

21. Don Mee Choi, Petite Manifesto (Newtown, AU: Vagabond Press, 2014).

22. Craig Santos Perez, From Unincorporated Territory [Hacha] (Kaawa, HI: Tinfish Press, 2008), 11.

23. Paul Lai, “Discontiguous States of America: The Paradox of Unincorporation in Craig Santos Perez’s Poetics of Chamorro Guam,” Journal of Transnational American Studies 3, no. 2 (2011): 14.

24. Craig Santos Perez, “The Page Transformed: A Conversation with Craig Santos Perez,” The Lantern Review, March, 12, 2010.

25. Perez, From Unincorporated Territory [Hacha], 87.

26. Perez, From Unincorporated Territory [Hacha], 15.

27. Craig Santos Perez, From Unincorporated Territory [Saina] (Richmond, CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2010), 111.

28. Craig Santos Perez, From Unincorporated Territory [Guma’] (Richmond, CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2014), 53.

29. Rudiger Kunow, “American Studies as Mobility Studies: Some Terms and Constellations,” in Re-Framing the Transnational Turn in American Studies, ed. Winfried Fluck, Donald E. Pease, and John Carlos Rowe (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2011), 252.