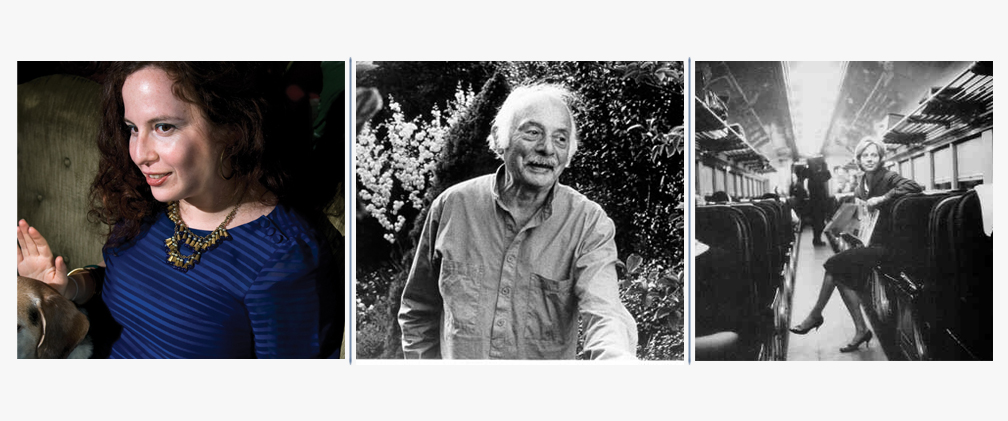

Kunitz and Guest in the KWH 1960 symposium

The 1960s Symposium at the Kelly Writers House happened last December and featured a varied list of speakers. Each one addressed the 1960s moment in American literary history, which could best be summed up by the books published around that time. It seemed like a fabulous event and I could certainly comment on every last minute of it. Below are just some of my thoughts on two parts: Al Filreis’s introduction and Erica Kaufman’s discussion of Barbara Guest’s book, The Location of Things.

The evening started with a short speech from the master of ceremonies — Al Filreis. Infused with his hallmark (and infectious) humor and charm, Filreis touched on some important ideas that served to frame the rest of the event. He mentioned Stanley Kunitz’s piece in Harper’s Magazine from late 1959, in which Kunitz said that there was no current “innovation in poetic technique […] it is rather a time in which the gains of past decades, particularly the 1920s, are being tested and consolidated.” [1] Filreis explained that Kunitz meant that the ’20s (as the peak of Modernism) was a time of aesthetic hijinks, but that the 1960s were simply going to be a time of modest consolidation. And it was Kunitz who set himself up not as an experimenter, but as a mature consolidator, praising poets like Robert Frost versus those like William Carlos Williams. Kunitz’s faulty ideas acted as foils for the rest of the talks; as Kunitz himself wrote, an experimentation of forms is a “resistance to forms is a longing versus a looking forward.” [2]

After listening to Filreis’s short talk, the entire event, and then Filreis’s talk again, I got a horrible, firey anger toward Kunitz. I tried to suppress it, but it came up again. Why? Because he was so bombastically shortsighted that it seems laughable in retrospect (and of course, this is the whole point of Filreis’s brilliant frame). Still, why did Kunitz say such things? Was it to put shame upon the experimentation of the ’60s? I continue to ponder and ponder his comment that a “resistence to forms is a longing” almost wholly because someone recently expressed to me a similar idea about craft and form that was equally bothersome. It was something to the effect that it is immature to write as if one is speaking, because then craft would not be evident. And what does that mean — what about Lunch Poems? Isn’t craft also supposed to be nonevident within forms? I am not sure. Some poets write in forms as if to say they did, while others are more nonchalant. And did Kunitz mean it is nostalgic to dream of risk? Are all new sound forms immature? No way! They are everything! And what of speech and the everyday meter, where meter comes from? Yes, the foil of Kunitz stoked a fire in the dragon that I am which will extend beyond this short commentary.

Another segment that interested me was Erica Kaufman’s discussion of Barbara Guest’s first book, The Location of Things, published in 1960. It is a gorgeous book and one of my favorites, too. In Kaufman’s discussion, she mentions that Guest reclaims gender through the act of writing, and so asserts that the act of writing is human and thus gendered. She also mentions that by redefining space in the book, Guest is also redefining the domestic.

Kaufman builds on this argument when she discusses Guests’ re-envisioning of the domestic space in the poems by using the definite (versus indefinite) article in her title. It is as if, Kaufman explains, Guest gains power over the house and writes “more than public speech,” but rather a series of poethical poems that create an alternative relationship between a woman’s voice and her relationship to things through a shifting persona. [3] In “The Hero Leaves His Ship,” she does become the all-knowing, trickstering, lyrical I, engaging with the history of poetry. As she writes, “I wonder if this new reality is going to destroy me. / There under the leaves a loaf […] Dear roots / Your slivers repair my throat when anguish / commences to heat and glow.” [4]

I am particularly interested in the arguments Kaufman makes, as I am forever thinking of the space a female poet occupies in a poem. If we think of the poets we often associate with this era (e.g. Plath and Sexton), there is a sense in which these poets are also trying to redefine their shifting relationships to both their lives and their poems. Female poets (like many others traditionally silenced in poetry) have a double duty: to craft language skillfully and beautifully while engaging the classic male voice, whether in concert with or against it. It seems that a way to do this is to create a shifting persona that can maneuver a multitude of voices and still have dominion over them. In The Location of Things, Guest does so. And in doing so, she does not become the modest consolidator of forms that Kunitz prophesizes for this era, but a historical compass for us all: a painter of text, who by engaging with her own relationships to language becomes a new creator of it.

Listening to the symposium, I have an overwhelming feeling of sadness to have missed it. The recordings give a sense that they document a room full of people who love poetry. And seriously, what could be better? During the talks, I kept thinking: Where was I? Why wasn’t I there? I was alive and in Philadelphia (and probably just three buildings away in December 2010), doing something likely less important. I should have been there with these amazing people. Thank goodness there are things like PennSound, so that it almost doesn’t matter. And that I can go into the space of these talks again and again, constantly reimagining their arguments and my own place within them.

[1] Stanley Kunitz, “American Poetry’s Silver Age,” Harper’s Magazine (October 1959): 173–79.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Erica Kaufman, “On Barbara Guest’s The Location of Things,” December 6, 2010, Kelly Writers House, University of Pennsylvania.

[4] Barbara Guest, Poems: The Location of Things, Archaics, The Open Skies (Garden City: Doubleday, 1962), 20–21.