These books need to be collaborated with

A review of Debrah Morkun's 'The Ida Pingala' and Aimee Herman's 'to go without blinking'

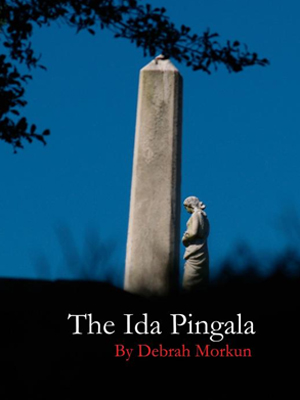

The Ida Pingala

The Ida Pingala

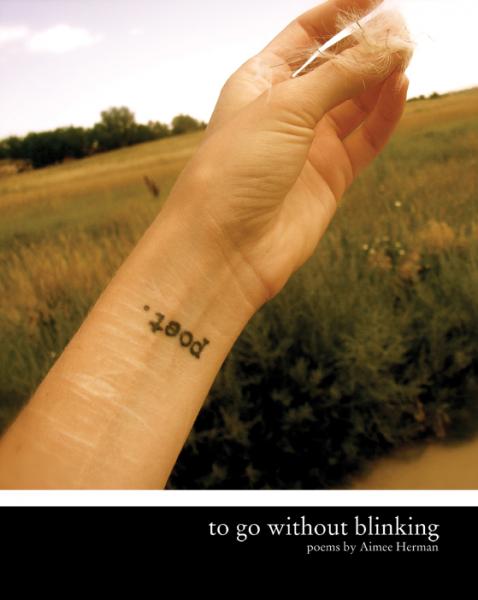

to go without blinking

to go without blinking

Debrah Morkun’s new book enacts commingling (“here is my torn dress made of semen”); is a non-monetary fiduciary — an ethical holding between the Ida Nadi (lunar Nadi, site of comfort, nurturing, said to control mental processes and to be the site of the “feminine” aspects of personality, represented by the color white (“the forest was open”)) and the Pingala Nadi (solar Nadi, stimulating, said to control vital somatic processes and oversee masculine aspects of personality, represented by the color red (“a virile member of the eternally repeated word”)).

This book is: “two ancient things combusting” … “sperm glass egg socket.”

Nadis are not nerves, they are channels; conduits. I often consider Nadis as elongated mini trenches. As veils removed from the vein for the sake of flow. Always to increase flow. If only, to increase flow toward pure desire. Morkun’s The Ida Pingala is a toward. A toward and a through. This toward and through is relevant in considerations and pursuits of Kundalini (coiled/corporeal energy), of which Morkun’s The Ida Pingala is interested.

Kundalini has an extremely compelling relation to the possibility of unlocking or inhabiting pure desire. This desire is not inherently in/of the genitals. It is located in the base of the human spine and needs to be cultivated toward the genitals. The Ida Pingala is a draw by libidinal amplitudes. It is by way of this libidinality that Morkun brings gender and sex (as elements capable of relation with each other and with other elements) into her book.

Kundalini has an extremely compelling relation to the possibility of unlocking or inhabiting pure desire. This desire is not inherently in/of the genitals. It is located in the base of the human spine and needs to be cultivated toward the genitals. The Ida Pingala is a draw by libidinal amplitudes. It is by way of this libidinality that Morkun brings gender and sex (as elements capable of relation with each other and with other elements) into her book.

The content of this book moves in and out of many different types of relations (from “a glittery Honda Civic” to “the halls of saints”). Objects, individuals and sensations interact here. The Ida Pingala (without particular delineation of such movements) funnels and simultaneously switches as matter passes through it. Is this book a handbook for working with the eroses of the psyche from within embodied states?

The Ida Pingala’s cover is comprised of a dual statue: exhibiting both a stone woman and a stone phallus. Here, seeming opposites are brought in aspect-based relation to each other; are in an energetic cull toward uniting. And we, as readers, are swallowed up in this funneling and switching.

The work (with uniting) that Morkun engages here, is something that reveals Morkun’s genius re: torque-instigations of previously perceived oppositions. This book is a virtuous hunt for fusions (“motley firmament”), for strange exposures and disclosures that are revealed by way of unforeseen or odd conjunctions. Whole view focused on overlapping; on certain studded myopias as they are amalgamated.

It is true that as we move from one Nadi to the next (the sunset to the sunrise to the sunset) we can learn to exercise one and two together in personal ways. But, this takes time — takes effort. Takes embodying duration and focus in order to get to “a tradition of eternity … tradition of hoisting.”

Hoisting as a way to host well, a lingam made of petals. A largess, being needfully translated by pearls.

***

Aimee Herman’s to go without blinking is a particular and fierce calisthenics (a “smothering [of] loins”) being performed around a deeply intended apparatus. Herman states in the intro of the book: “this body of text practices trilingualism and contraction.” I would go so far as to say that the book also practices triangulating and contradiction. With these four activisms acting in combination, we as readers are able to experience tgwb as something that both haunts us and hinges us. I would not go so far as to say that we ever get a hug (or anything approximating it) in this book, but we do get a hinge, and as we move through it we find ourselves desperately swinging.

To move by choice through something of such “sacred disturbance,” as tgwb is, is important. I am saying that this book needs to be collaborated with; needs us to collaborate with it. There are various points (in the process of moving through) where we are seduced into staying. It is almost as if an under-voice says: “just keep reading,” and we do. We must. Herman recognizes that the deep sway of her workings (in twgb) are not nice or simple or pretty. They are violent and juicy (they need to be so). They are “slick back polynomial” driven by an accumulation of jolt-like parts. The aspects of this book perform like a sweaty “bravado of sprouts fondling soil.”

In tgwb we are barraged (I always mean that as a compliment) with gritty and edgy content (“She was persuaded to use her cunt as a cabinet” / “Gabriel from Chickopee tried to fuck the gay out of me and almost got away with it” / “I would tear out my cunt and give you mine just so you could fondle decontamination”) — so much pertinent information regarding identities, genders, aesthetics, wishes, body realities, artifice, suffering, etc. I feel like Herman has somehow gotten it all into this marvelous book!

In tgwb we are barraged (I always mean that as a compliment) with gritty and edgy content (“She was persuaded to use her cunt as a cabinet” / “Gabriel from Chickopee tried to fuck the gay out of me and almost got away with it” / “I would tear out my cunt and give you mine just so you could fondle decontamination”) — so much pertinent information regarding identities, genders, aesthetics, wishes, body realities, artifice, suffering, etc. I feel like Herman has somehow gotten it all into this marvelous book!

If we are conscious as we go through metallurgical transformations, what remains? These poems. These poems whereby beauty is able to be an embodiment of disparate aspects: “She thinks of beautiful women, wearing her fingers, wrinkled, like an article of clothing” / “She just wanted to know what it would feel like to be feminine: pigment of wax” / “When the stick of honey is gone, one must turn toward the bitter.” Herman turns us. We are here and we are gathering this butter.

These scenic genital-details are anything but gentle; I can hear my own scream building wildly as I read them. I scream inside of me for the arousal I feel. I scream inside of me for the anger I feel. I scream inside of me for the altered-ness I feel. I am not sure if Herman was meaning to induce readers to such states, but by sharing her life and visions, these scars — it has become impossible that we not feel these things right along with her.

At its core, tgwb is much like the heartfelt narratives of Lidia Yuknavitch’s novels, but Herman’s pieces are schisms of a form slowly coming together. By body, by light, by night. No Aimee, you are not the “only one to notice the night.” Because you are showing it, sharing it by way of tgwb, I notice this night with you.

And yes, dear Aimee, when you die, I will play at your funeral. The song will be a full-handed violin melody reminiscent of the image of whole fruits inside of an enormous, ever elongating mouth: “washing [your psychic] mouth with fruit carcass” as a way to counteract all effects of the impositions you have encountered.