Registers of breath: On origins and concession

A review of 'The Concession Stand: Exaptation at the Margins'

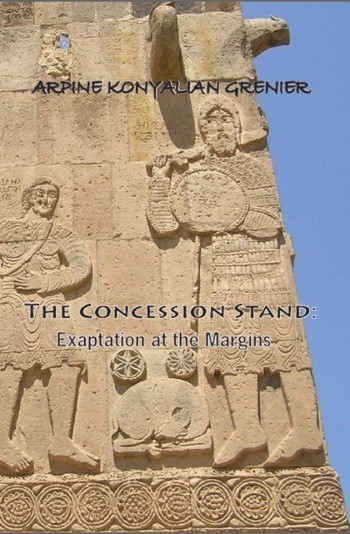

The Concession Stand: Exaptation at the Margins

The Concession Stand: Exaptation at the Margins

Several pages into her new book The Concession Stand: Exaptation at the Margins, Arpine Konyalian Grenier refers to William Bronk’s Life Supports (1981) and Manifest; And Furthermore (1987). Given the flood of information with which she ceaselessly inundates the reader — dovetailing with her decidedly postmodern sensibility and concomitant narrative technique — it would be easy enough to take these allusions simply as further evidence of Grenier’s wide-ranging literary interests and remarkable erudition in general. However, in a characteristic form of hers that might be likened to the Japanese haibun, where prose is followed by haiku that does not always bear an obvious relation, Grenier juxtaposes a rapid-fire assessment of Bronk’s poetry with her own spare verse. Here, however, the connection is rendered overt through simile:

I sense a conceding that may have eventually led him to silence, spawned and sired.

as if at the concession stand

cured of speech[1]

Not only does this trope return us to the title of Grenier’s collection (part of the work’s postmodernity is its contesting of literary boundaries, though generically there are eight essays), but also it suggests a link between Bronk and Grenier that might be overlooked amidst the explosive connections she recurrently makes between writers and ideas, technically expressed through her relentless employment of fractured syntax.

Though Grenier seems remarkably free of anxiety of influence, her observations about Bronk bring to mind a certain literary line deserving our consideration. William Bronk, as some readers will recall, belongs to the very beginning of the long history of Cid Corman’s Origin magazine. In fact, a poem by Bronk appeared in Origin 1.1 (Spring 1951), and he was then cofeatured in the third issue of this series (Fall 1951). Interestingly, given Grenier’s lines above (and her title), Corman later wrote that Bronk’s was “a poetry without concessions.”[2]

The first featured poet in Origin, however, was Charles Olson, with Robert Creeley following in the second issue. Several of Olson’s letters to Vincent Ferrini were included by Corman in Origin 1.1, and the conclusion to the first of these is highly relevant to Grenier’s technique in Olson’s observations about syntax:

The first featured poet in Origin, however, was Charles Olson, with Robert Creeley following in the second issue. Several of Olson’s letters to Vincent Ferrini were included by Corman in Origin 1.1, and the conclusion to the first of these is highly relevant to Grenier’s technique in Olson’s observations about syntax:

We are huge, and roily. Mixed up. Even by perpendicular penetrations, we are discontinuous. (What I did not stress — in PV [“Projective Verse”] — enough, perhaps, is this business, of, how, when traditions go, the DISCONTINUOUS becomes the greener place. (For example, all that on syntax, is due to, this: we have to kick sentences in the face here, if we are going to express the going reality from down in you, and me, and any other man who is going for center: which means language has to be found out, anew [...][3]

Consider the following from Grenier’s third essay in her collection, “There but not There”:

Would poetry, therefore, restrain the intent of literary scholars and patrons of cultural institutions since it is a culturally indefinite voyage with no external goal, refusing the tyranny of arrival? Let intent be the risk quantum levels have taken. Let a new syntax be derived for a new semantics, evolving as we speak — itself and its proxy adding to self while emptying self, interrupting the prevailing homogeneity. (29)

An “Armenian-American from Beirut, Lebanon, where a variety of religions, languages and nationalities coexist(ed) in a rare mixture of oriental simultaneity and occidental individualism” (43), Grenier writes as an ex-centric woman, kicking sentences in the face as she moves away from, yet assaults, the center from the margins. Still, Olson’s reference to his landmark essay “Projective Verse” reminds us of another common ground of their poetics (also shared with Creeley), the importance of breath.

Olson laid down, “that verse will only do in which a poet manages to register both the acquisitions of his ear and the pressures of his breath.” Grenier has registered the pressures of her breath in her mastery of the long line:

It is a small and round world indeed

codignly yellow

there is no resistance when color takes off indifferent to light so

and only because what is mind shackles time as collateral

as if to remind the bodiless have entered us and the plot is

engage think as always bottom up re mind

states matter to states as they greet parallel brains

faith based or hope out there serial prudence

principled to curate reason

I belong to and am under the rule of the supernal

a willingness and acanthus fields (let us play

games) sub urban thought provides

fortitude (50-51)

However, Grenier’s poetry moves in two directions:

If then you scrapped it all

love wills through still

long time bristled

edges of

wit (15)

In reading the above lines, I’m reminded of a conversation I had with the Canadian poet Daphne Marlatt, whom Corman also featured in Origin. An accomplished practitioner of the long line, as in her Steveston poems, as well as short-line verse, Marlatt “used a lot of the etymological Olson side” in her feminist poetry, and found Creeley, with whom she studied as an undergraduate, “one of the great prose stylists.” However, it was from Cid Corman that she learned “the value of the short line with a word at the end at which you pivot meaning.” It’s worth rereading Grenier’s short lines in this light.

When Corman came to Japan in 1958, he carried Olson’s insistence upon the primacy of breath into his new passion for the dramatic art of Noh, even becoming a pupil of utai (the choral element of Noh) under Takashi Kawamura in Kyoto. Corman’s study of Noh has a clear relation to his own poetics. The preliminary material to his and Will Petersen’s translation of Zeami’s Yashima, which appeared in Origin 2.3, includes the following:

This version of a Noh play attempts to give the reader the closest possible sense of the Noh experience. By exact articulation of syllables an idea perhaps is gained of the utai, the sounding of the text, its curious quantities that often break against speech rhythms and even the rhythms we are accustomed to find in the accent of “meaning” in English. If some feeling, then, of strict breathing, of the most careful pacing and intonation, the dance of the words, occur, we shall be content.[4]

Both Corman and Petersen, who was at this time managing editor of Origin, recognized what the latter, in a letter to Corman, described as “the clear contingency of breath as body’s relation to everything.”[5]

This contingency was essential to Corman’s poetics. His pioneering work with oral poetry accentuated his “growing recognition that the fundamental act of poetry, as of everything else, is the affirmation of breathing, the act of living in dying.” He contended:

If your words, your syllables, your lines and stanzas, every comma, every break, do not hang on the spine of breath in them, no plotted or pieced structural model will do any good. The body will be dead and you will have simply painted a corpse, or at best, embalmed it.

To breathe words is to breed words. Invisible flower. Substantive nothingness. To know that every breath, and thus every utterance, IS a matter of life and death. Until this act is recognized and entered, no poetry exists. And when it happens, why everything happens; it is, as it is, an all-poetry [...][6]

Grenier’s poetry clearly recognizes this act, enters this act, and the result is “an all-poetry” that, like Corman’s, embraces emptiness, or mu. (Corman paradoxically saw mu as in fact fullness, stating in a radio interview that “The empty space that you start from is the vastness, is the infinite.”)

Apropos, Grenier writes that, to poets, “language is a vision concerning (but not having) thought, recalling the null from which it comes forth [...]” (12). She quotes Dennis Lee, “a good piece of writing bespeaks encounter with emptiness as its source” (26), adding that when we discover the divine in the fabric of the everyday, “we catch a glimpse of the void itself, that regenerative, all-consuming nothingness from which we all emerge, into which we are destined to return. Poetry allows this moment, this breath for emanated being (Borthwick) — the paradox of locating the site of one’s dwelling in the world by embracing self-forgetting and celebrating one’s estrangement and otherness” (28).

Grenier’s essays are a sustained and challenging expression of her poetics, predicated upon her recognition of “khora, the non-place we arc and ride, the gift and counter-gift (meaning discourse) we inhabit, distorting and often destroying to rework to fit “ (72). Here she leads into another of her haibun-like constructions:

Celebrate the experience, the pre-origin a bastard’s logic dwells in.

orphaned discourse not

orphaned logos (72)

And then: “The blur between speech and silence is magical then, is life. Be open to its transformation and betrayal” (73). Sound, she posits, “is full when your abdomen rises and muted when it falls across truncated dorsal integuments. Song, always a priority. Each impact an entrance, sudden departure, vigilant eye. Do not be alarmed, eviscerate” (74).

And then: “The blur between speech and silence is magical then, is life. Be open to its transformation and betrayal” (73). Sound, she posits, “is full when your abdomen rises and muted when it falls across truncated dorsal integuments. Song, always a priority. Each impact an entrance, sudden departure, vigilant eye. Do not be alarmed, eviscerate” (74).

My argument that Grenier’s poetics has multiple connections to Corman and the Origin poets is by no means gratuitous, extending far beyond the nod in her title to what Corman described as Bronk’s theme of “language failure itself and the palpable deception we practise on ourselves through it.”[7] We should not overlook that during the early 1980s Grenier studied poetry under yet another contributor to Origin, Clayton Eshleman, at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, where he was Dreyfuss Poet in Residence. When I recently queried her about this experience, she replied that she very much liked the way Eshleman taught poetry — “if there’s such a thing as teaching poetry,” she added.

When Cid Corman died in 2004, Eshleman wrote a couple of memorial pieces registering the impact that Origin had upon him from 1960 onward. Eshleman acknowledged that through Origin he was introduced to Olson, Creeley and the Black Mountain poets as well as a number of European poets whose work appeared there in translation. The mentor-apprenticeship association that Corman and he developed dated back to 1961, when he visited Corman in San Francisco, then developed during a period of over two years when Eshleman and his wife resided in Kyoto. There, on a weekly basis, he would walk or motorcycle to The Muse coffee shop, where Corman held court during evenings, influencing Eshleman’s development not only as an editor and translator but also “as a dedicated worker in the art of poetry.”[8] Curiously, Eshleman doesn’t mention here Corman’s influence as a teacher, for a number of poets in Japan whom I have interviewed over the past few years — Scott Watson and Taylor Mignon come immediately to mind — have remarked upon this dimension of Corman’s mentoring. Presumably what Grenier appreciated in Eshleman’s teaching was not unrelated to what Corman had taught Eshleman about his craft.

As for editing, Eshleman went on to produce Caterpillar during the late 1960s and early 1970s, then founded Sulfur during the time Grenier was studying with him at Cal Tech. (Some of her earlier poems appeared in Sulfur, which ran until the year 2000.) Significantly, Eshlemam notes that Cid’s poetics, “based for the most part on the lyric short poem,” did not accommodate his own “sense of the wide-ranging diversity in 20th century international poetry.”[9] This aspect of Eshleman’s poetics — reflected in his editorial choices — connects to an important feature of Grenier’s work that has not gone unnoticed by critics. Perhaps the best-known assessment of her writing has been Kevin Killian’s description of “her explosive gift of shooting words at the page in glee, the gift for metaphor and a complimentary [sic] one that knows how to organize sprawling material [...] takes us out of our provincial concentration on American life to encompass broader social and geopolitical issues.”[10]

Of course, subsequent to his “poetic apprenticeship” under Corman, Eshleman has equally distinguished himself as a translator. His cotranslation of César Vallejo’s Complete Posthumous Poetry received the National Book Award in 1979 and, more recently, Eshleman’s translation of The Complete Poetry of Cesar Vallejo won the 2008 Harold Morton Landon Translation Award, as well as being shortlisted for the International Griffin Poetry Prize. Without pressing the point too much, one might note that the second essay in Grenier’s book, titled “TB as Something Willed,” addresses the whole business of translation with concerns redolent of those raised by Corman and Eshleman:

With translating, every word, phrase or metrical decision reinforces the difference between one’s interpretation and the original. Often, giving in to the rules of, say English, is a deterrent to the potency of the poem in translation — to its casting of a spell. There is no law or grammar where writing happens. The translator is outside the stasis translating imposes on the text, rips and all, outside of what’s controllable or not, what’s orderable or not, link to link to ding ding in nothing but authenticity, dropping code to let the lines breathe, to re-form. (23-24)

And:

Translation bastardization works because it creates movement that eludes measures of control. It escapes the gravitational field of historicity and cultural difference. (24)

I am here reminded of Eshleman’s comments on Volume One of Corman’s monumental OF, where he “was shocked to find Cid’s translations there — of Homer, Sophocles, Catullus, Tao Chi’ien, Montale, Villon, Rimbaud, Bashõ, Mallarmé, Rilke, Ungaretti, Char, Celan, Artaud, and Scotellaro — treated as Corman poems.”[11] Mightn’t Grenier’s observations be used to rationalize Corman’s appropriations?

That Grenier also trained as a scientist in the field of chemistry and physics, being particularly influenced by Peter Higgs of the “Higgs field” and Higgs mechanism — a consequence of which is the theoretical Higgs boson — directs us to another crucial aspect of her writing, the application of science to her poetics. (Here the word “field” applies more to the poetry of Michael McClure and Chris Dewdney than to the theoretical constructs of Charles Olson.) I don’t pretend to understand the full implications of, say, Grenier’s references to Schroedinger’s cat, yet it is impossible to ignore this dimension of her work:

Ever to bring about the (horizontal) wisdom of a matriarchy, not in contrast to, but collaboration with the vertical/ patriarchal, ever to consider the feminine as life's (fluid) currency through the pluralities of voice and culture, modulating as the turbulent orients in space where it simultaneously emanates and observes itself. There lies magic. Not unlike DNA, it reconfigures to differentiate. There can be no prediction even under the maximum conditions of control. Magic, that's something else. Let's maintain the magic of possibility, a curatorial possibility. As thought relates to language after the fact, like Schroedinger's cat does (to Schroedinger), one abs it (thought), as in ab-solve. My hope thrives in such obligation, in such moot obligation to produce a perfect poem I know full well I will never come by. (8)

Feeling helplessly out of my league in trying to come to terms with quantum mechanics, I finally broke down and sent Grenier an electronic message inquiring about the relation of science to her writing. She replied, “yes science as in Higgs’ field (which they also call the God particle and i so despise the phrase...Peter Higgs is still alive) and all those other references...which by the way are in nature and life and not just in scientific findings...actually it happens in reverse with science...for which reason I abandoned it for art...art is sooo much more alive and kicking :):)”

Still, consider the subtitle of Grenier’s book. How many readers will admit to not knowing the meaning of “exaptation”? It’s not the sort of word one finds in Urban Dictionary. However, the American Heritage Dictionary lists it as a biological term meaning “the utilization of a structure or feature for a function other than that for which it was developed through natural selection.” I queried Grenier about her subtitle at the same time I wrote her about Higgs and Schroedinger’s cat. She replied, “with exaptation there is a component of ‘will’ as i introduce it...similar to Nietzsche maybe but a bit more human and artful as opposed to Germanic and existential...more transverse.”

Where is this all leading? Where exactly is the exaptation at the margins? Clearly Grenier is writing about and because of the evolution of language, of syntax:

However, the act of writing continues. One is always en face de X, scraping against deaf matter, responding to its systole and diastole with vigor and swagger. If we were to look up the word “oppressed” in Arabic, the dictionary (al-qamous) would indicate the root and related words like press, depress, repress, impress, suppress. “Oppressed” is different, however. Oppressed people’s voices are muffled because with oppression, soul and spirit are implicated. What oppresses does not occlude either, as one is always in the process of willing the other into existence, through language. Love is at play here and is catching. (9)

Grenier’s sophisticated commingling of science and etymology is a fixture of her writing, exhibiting a larger assimilative tendency that has also not gone unnoticed. As Gerald Locklin has written on the back cover:

Arpine is one of the few living American writers to whose works the term “profound” may be meaningfully affixed. She has as capacious a consciousness as any I have ever encountered: Science weds Philosophy and yields the Poetic and the Fictive (in Wallace Stevens’ sense). Her mind is fertile like the garden and pond of Giverny. To fully appreciate her writings one must strive to emulate her genius for synthesizing the currents of a personal and intellectual history.

At the same time, Grenier frequently disarms us with forthright, axiomatic (almost homiletic) observations, some her own and others borrowed or reinterpreted, that strike the reader as the sort of thoughts Thoreau might have entertained had he found himself stranded in post-history. My favorites include:

Beware of judgment, lean on art, someone said. And J.F. Kennedy said, When power leads man to his arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations, when power narrows the areas of man’s concerns, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of experience. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses. Smell the cologne, I’ll say. (13)

Beware of matter that breeds identity as Baal demands total allegiance. (20)

And:

Narcissism with many faces but no wings, for which reason, the misconception of power has driven mankind to (external) power, to dominate. Fear has dampened our wisdom, and guilt has buried our moral reach. We feel the symptoms of our dis-ease yet do not know where to turn, do not want to know either. We are stars that wallow in sophisticated metaphors, lest we shed our fear-laden mask of sterility (it is our haven, an energy and emotion impoverished heaven). But there’s hope and wishes for every reality gone mad, and reverence, not to respect but to honor those very histories that brought us to where we are. Let us rid our selves from anti-concepts, ask questions instead of providing information or judging some agenda. Let us feel the warmth of our blood, salute its preciousness so reason and emotion can dance together, the cognitive and the normative. (33)

These ruminations build upon each other to extend our understanding of Grenier’s poetics.

Even the penultimate essay in the collection, the one chapter that initially seems at odds with the others, serves this function. An account of Grenier’s participation in the 2009 Dink Memorial Workshop at Sabanci University in Istanbul, “A Place in the Sun, Malgre Sangre” contains a good deal of what might be termed travelogue, detailing Grenier’s experience of Istanbul — visits to restaurants and cafés, Misir Carsisi (the Spice Bazaar), Galata Tower, the Hyppodrome, Haghia Sophia, Yerebatan Sarnici, Topkapi Palace, and other places — as well as a short trip to the cities of Konya and Aksaray; still, it serves an integral purpose within the larger design of the essays. For it is in this essay that Grenier, coming from an oppressive marginalized culture, the daughter of an Armenian genocide survivor, lovingly records the minutiae of her icli (hearty) and tatli (sweet) maiden visit to Turkey, whose relation to Armenia certainly requires no gloss.

Prior to her departure to Turkey, Grenier knows what she’s after: “Having already noticed how much we’re alike, I now want and need to learn to accept that, to accept and love the unknown I come from” (55). Upon hearing an announcement in French at the airport in Dallas, she reflects:

I’m surrounded by languages I recognize or don’t. Have I been too long away from these sounds and minds? Always a misfit this I and yet, this here feels fit/ unfit and familiar in its strangeness. So, to be familiar with a strangeness or to find strangeness in the familiar, that’s all pulse, isn’t it? Otherwise, life is unbearable. Agency is fluid, remember? Moving (velocity?) allows sight when screens are in the way. (55)

In Turkey, she will be experiencing not only the culture of her ancestry but also the culture from which she had run away. The people she encounters there will prove agents of connection.

In this essay Grenier foregrounds the binding relationships she develops with participants in the workshop on Gender, Ethnicity and the Nation-State: Anatolia and its Neighboring Regions, a theme that brings together representatives of fifteen countries, with a commingling of Turks and Armenians. When asked to participate in an artist’s diasporan video project, Grenier rejoins, “But everyone is diasporan [...] there but not there, clueless, ortancil (in the middle), and older is not necessarily elder! I want to loosen and undo matter, I also need glue” (58). Adhesion comes through group solidarity; on the last evening of the workshop, she enjoys holding onto others, refusing to let go, on a rush-hour train ride to a café where the group is entertained by a gypsy family’s “songs and dances full of love and hope and passion,” another reminder that “[w]e’re all alike as we’re different” (59). She now wants and needs “to learn to love” this condition, “shifting and turning without undoing myself, without unseeing and dismissing others either. That will help me love myself someday, love and accept the oppression I come from, the oppression that has released these new days for me (us).” (60)

Grenier feels immediately at home with the locals, both in and without Istanbul. She also describes with great affection her guides on her excursions — Burcu, a Turkish woman who shows her about Istanbul, and Kadir, a twenty-year old Konya University student volunteer who squires her about Konya, from which Grenier’s father heralded, as well as Aksaray. She parts from Burcu with a hug, knowing they will remain in touch, and regards Kadir as “a reflection of what Turkey is slowing becoming these days — the best of the East and the West” (66). In telling Burcu about a Turkish and Armenian organization called Biz Myassine (We Together), Grenier espouses, “Connection is a basic need, humbling and addictive yes, but there is beauty in the connect. I am after that beauty” (62). She comes away from Turkey remembering “that agency is fluid, and that the functionality of identities is identity too, a gate that can slam shut or open. I’ll go through it not knowing what’s on the other side. Who is to say when which creates, what. The only what I know is the gill I breathe from” (67). We are back to breath.

In her first essay, Grenier reflects, “Not part of a qualified culture nor speaking on behalf of one, busy with dimension while weary and leery of its shadow, I live with the urgency to fuse what is outside of time with what is within, often at the expense of meaning or syntax, to reconcile as if, in response to be wounded” (13). Wounded by (and yet a survivor of) the historic past, she, as poet, “is calling, calling at unbearable proximity to the need to do something about all that does not follow the routine of civilization, the functions of circumscribe/ control/ eliminate. By nature the poet is healer, yes, but who sponsors the healer when the lights go out?” (11)

In her final essay, in many ways a coda to the previous seven, Grenier addresses the plight of the poet in a world irreverent toward bardic magic and healing. Here she muses upon the “asthmatic climate” created by convictions and “those things done in the name of love, of son or daughter, of God, of country” (70):

Shall we replace or redefine morality then? Laws cannot define history anymore than history can define laws, humans do that. Do not confuse depth with complexity, describing is different from explaining. Power laws can only be described, not explained. Often depth and complexity are in competition. Remember Gell-Mann’s sympathetic magic. Theorizing is as futile as rationalizing. Moreover, selection pressures are not consistent and often do not make sense. Logic is for the birds that do not fly but think they do. (71)

She concludes in her (postmodern) homiletic Thoreauvian and scientific vein:

Consider self part of the other, all seems fair then, the purgative, the illuminative, the unitive. Seeking retroactive meaning is toil and trouble, so are building techniques, recipes, rites, amulets. Let’s scratch off to a blank slate instead, let’s interrupt and disrupt the scraps. They’re throbbing to rebuild. Do not look at the whole to annotate, look at the parts and pretend. Think of how matter behaves differently under different conditions. You are such matter. Center and periphery are mythical allusions. No pole position survives physicality, forehead to ground, the fez. (72)

Yes, yes, the beauty’s actually in the connect, for which reason, one is often paralyzed by the passion that drives it. So passion yes. Detachment, only as non-attachment. No anger, yes admiration, sympathy, so much sympathy. Nothing casual, never casual, simply liberated from the tyranny of words and logic, after what really matters, after what comes next — the boundless, creeping along realities withholding echo. Exorcised pulse. Mind angle and trajectory as switch and turn are about to follow [...] Breathe love. Noise will subside. (73)

We need contact dear, yeah contact. That develops syntax far lovelier than biology or facts, as love does not fail and sentences do not restrict the soul to just word parsings [...] Speech exerts to overcome excess. Replace the chatter with the silence of those who could but did not speak, undo mimetic shackles to experience all of history — the now, and (Derrida’s) what is yet to come. (81)

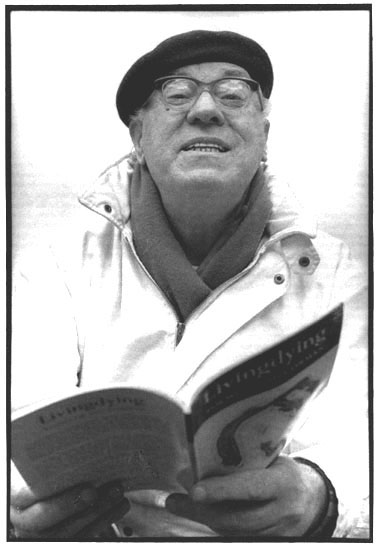

In these passages we are at the heart of Grenier’s poetics. There are all sorts of nuances here, and in her quotation of Zen Master Daisetz Suzuki — “discard fact, go after legend and imagination, then you are dying and not dying, otherwise you are living your death” (77) — I am again reminded of Cid Corman, whose poetics is best summed up by his mantra “Poetry is life, life is poetry,” as well as by the title of one of his best-known collections, Livingdying. (Corman’s minimalism, a sustained assault on verbal deception, replaces poetic chatter with the silence of Noh, the interval, or ma.)

Returning to the Origin poets Charles Olson and William Bronk: both were strongly rooted in place — Olson’s Gloucester, Massachusetts, and Bronk’s Hudson Falls, New York State. (Another of the early Origin poets, Gary Snyder, evinces this sense of place through his bioregionalism.) Sense of place gives way in Grenier’s writing to an overwhelming and decidedly postmodern sense of deracination. The Armenian-American from Beirut writes,

I have no mother tongue as my mother tongue has lost me. I implode with this loss, seeking the chaos sustaining the world of languages with a voice that has the body and place of an absent body, after a derivative of the past whereby the new would occur, time and history abolished because of what escapes or survives the disintegration of experience. (43)

(One of her real joys in Turkey was reclaiming part of her linguistic heritage.) On the same page she further records, “As daughter of orphaned parents, I experience identity as a self consuming artifact that hopes to deliver cross-cultural connections while it curates itself, the curating hopefully endorsing commonality as a continuous and inclusive enterprise rather than a dichotomous or hierarchical one, the longing to connect just because we’re human overshadowing the politic of the human.”

I find a connection here between her writing and that of the environmental theorist Ursula Heise, who argues that

the environmentalist emphasis on restoring individuals’ sense of place [...] becomes a visionary dead end if it is understood as a founding ideological principle or a principal didactic means of guiding individuals and communities back to nature. Rather than focusing on the recuperation of a sense of place, environmentalism needs to foster an understanding of how a wide variety of both natural and cultural places and processes are connected and shape each other around the world, and how human impact affects and changes this connectedness.[12]

It is exactly this sort of awareness that informs Grenier’s poetics. If we take the famous formula that was passed from Creeley to Denise Levertov — “Form is never more than the extension of content” becoming “Form is never more than the revelation of content” — we can see that Grenier’s search for liberation from the tyranny of words and logic is inextricably tied to her quest for contact and connectedness. This need eschews capitalist globalization as “stop-child to the digital world” (15), being cosmopolitan in nature. Grenier “open[s] hearts and minds to explore shared and intersecting pasts” (47). To return to her title:

The poet wants to appropriate the universality of ontology in order to testify to a universal destiny within l’experience vecu, continually redeeming the you and the me into a (Buber) us, facing a new space-time, that of hunger and light by the concession stand where, through the ethics of love, all and its trade-offs are laid out, for mutuality. (11-12)

1. Arpine Konyalian Grenier, The Concession Stand: Exaptation at the Margins (Rockhampton, Australia: Otoliths, 2011), 10.

2. Cid Corman, William Bronk: An Essay (Carrboro, NC: Truck Press, 1976), v.

3. Charles Olson, letter to Vincent Ferrini, 7 November 1950, Origin 1, no. 1 (Spring 1951): 6.

4. Cid Corman [and Will Petersen], “Translators’ Note [to Yashima]” Origin 2, No. 3 (October 1961): 17.

5. Will Petersen. Letter to Cid Corman, 27 December 1960. MS. Corman Collection, III, The Lilly Library, Indiana University. Qtd. by permission.

6. Cid Corman, “From a Letter, November 1959.” Mimeograph, Real Theatre notebook, author’s collection of Corman mss., 6.

8. Clayton Eshleman’s two published tributes to Corman were “What Brought You Here Will Take You Hence: A Poetic Apprenticeship in Kyoto,” Poets & Writers (January/February 2005): 56- 61, and “Cid,” Cipher Journal. http://cipherjournal.com/html/eshleman_cid.html. The quotation is taken from page one of the latter.

10. Kevin Killian, qtd. in “New Volume of Poetry by Arpine Konyalian Grenier,” Armenian Poetry Project, 30 December 2007. http://armenian-poetry.blogspot.com/2007/12/new-volume-of-poetry-by-arpi....

11. Eshleman, “What Brought You Here Will Take You Hence,” 60.

12. Ursula K. Heise, Sense of Place and Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 21.