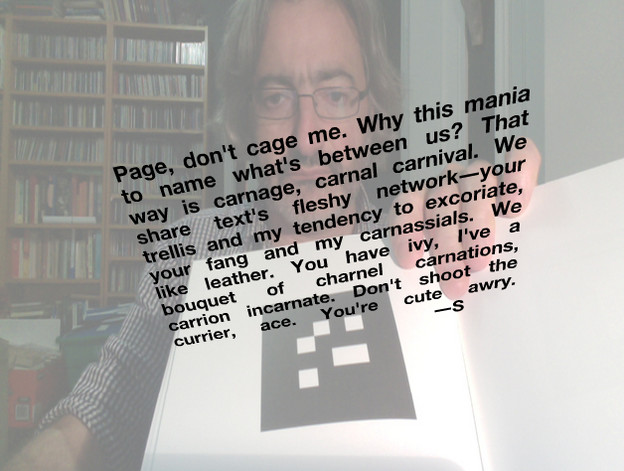

Page, don't cage me

The visual poetry of Amaranth Borsuk & Brad Bouse (in) between page and screen.

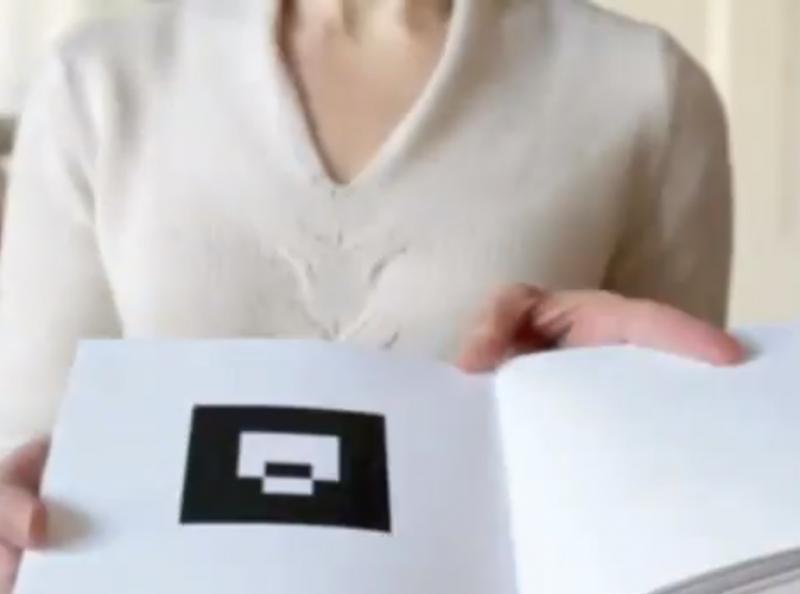

Dear Reader, open the pages of Between Page and Screen. Nothing but elegantly simple AR (augmented reality) codes. But then you point your browser (and here, Reader, I think of you, too, as browser) at the book’s website and hold the book within range of your computer’s webcam.

Where is the text? The text is a (g)host.

In Amaranth Borsuk & Brad Bouse's Between Page and Screen, the text literally hovers between page and screen. But of course, this, too, isn’t quite true. It only appears to appear in the virtual air between the reader and the website.

Between reader and writer. Between Page and Screen appears eponymously between page and screen. The text hovers like a djinn released, over the page. Reading ‘incarnate’ in an illusion.

And the reader? The reader is in the text. I literally see myself and my shelves through the text. “Page, don’t cage me.” Dear Reader, I see you seeing yourself.

But the reader literally controls the text. Can move the text.

Like a horse after the barn doors have been left open, reading is destablilized.

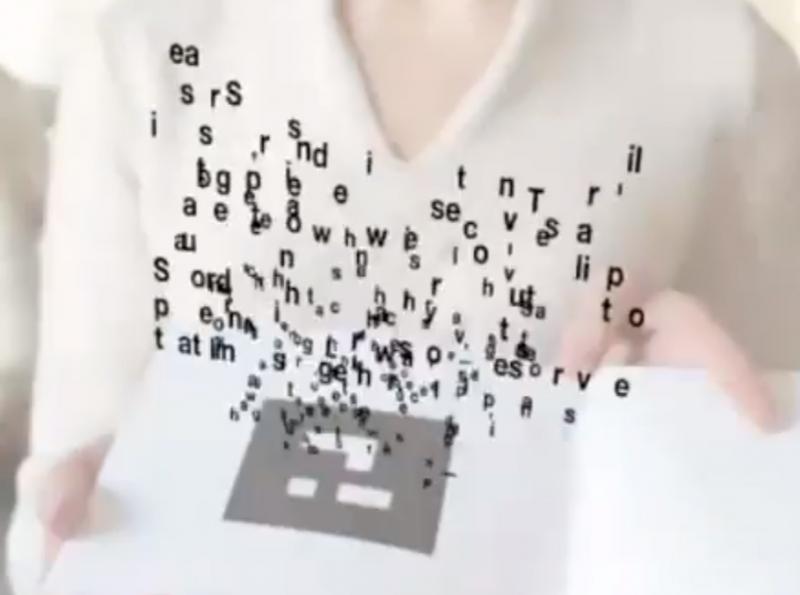

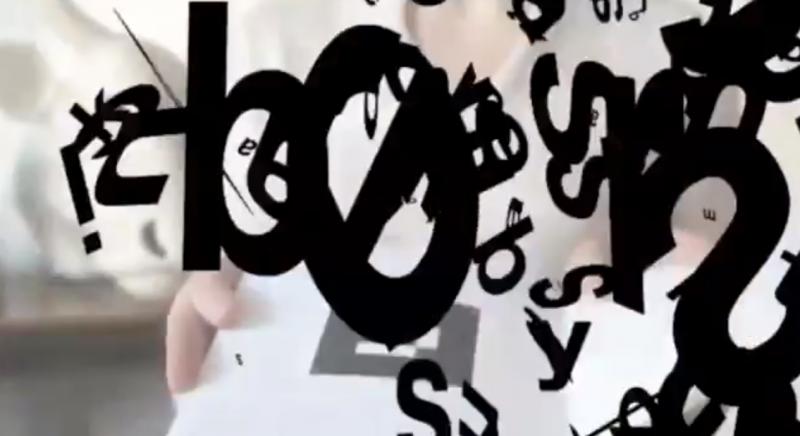

It’s left the cage of the page. It has burst out and, shakily, like a filly (or philology) balances, each movement of the reader’s handheld page, shaking its fragile presence.

The text itself isn’t stable either: Turn a page and it disperses, a “bouquet” of glyphic utterflies.

The codex has been destabilized by code. Computer code.

The symbiosis of reader and writer. Text and reader. Between page and screen, web and book, reader and writer. Both/and.

The book is a Ouija-board and reading is a séance. The text is a (g)host.

I spoke with Amaranth Borsuk:

GB: There’s a process of discovery or uncovery in figuring out how the book ‘works.’ There’s also a process of developing the required finesse in order to read it—perhaps reminiscent of the skills one has to develop in order to play a video game or use a updated version of a piece of technology. How do you imagine a reader ‘reading’ this text?

AB: You’re absolutely right that this is a book we must learn to read, training the body to hold and turn, to steady and straighten. But those are habits we also learned as children the first time someone put a tome in our laps. In re-learning to read, hopefully the reader is reminded that the book has always structured our relationship with it. I think there is more than one way to “read” this text, whether one spends time with the poems engaging in their etymological wordplay or whether one simply plays with the words, bouncing them around onscreen and watching them dance and fly apart. Reading is always a physical engagement with a surface, and hopefully this disorienting process reminds us of the body’s presence.

GB: The physical book (or as Coach House Books terms it, ‘the fetish object formerly known as book’) is a beautiful object. Minimalist and well designed, the black and white squares (AR codes) have an iconic simplicity that is appealing. But these codes aren’t just text, they are each an interface. A controller. And so, as reader, I make the connection between the fact that visual language, beyond its aesthetic appeal, can be a controller or interface when pointed in the right direction, when you understand its context and know how to use it, or if you understand what it ‘does.’ Can you speak about the visual aspect of the work?

AB: The visual aspect is central to me in how the text makes meaning—both literally, in that no text appears without those markers, and figuratively in the questions they raise about the encoded nature of language, about where the book’s meaning inheres, and about the legibility of page and screen (How do we read the book without a camera? What happens to the book when the site is defunct and vice versa?). In terms of the markers’ simplicity, they are built on the structure of FLARTOOLKIT, the open source software Brad used to program the website, so developing them was a lot like writing poetry in a given form or under a constraint (the asymmetrical grid). We liked the minimalism of those black squares, and one of our key tasks was to make each page distinct from the next to allow a certain memorability for the reader, since there are no page numbers.

I like the idea of the marker as a controller. We are not controlled by it, but rather our manipulation of that controller, our intervention, brings the text to life. Without a reader, there is no text—the book is inert, whether we are talking about augmented reality poems or a triple-decker novel. It strikes me that what you say about visual language, that it “can be a controller or interface when pointed in the right direction, when you understand its context and know how to use it, or if you understand what it ‘does,” applies equally well to all/any language. We need to learn to read the system that imbues words with meaning (linguistic, cultural, and political codes). This is the basis of signification—the act of translation that happens every time we read.

GB: The text of Between Page and Screen is a series of letters between “Page” and “Screen.” (I feel like we, speaking here, are their cousins: Reader and Writer.) Page and Screen write to each other through a trellis of text derived from the etymology of ‘page’ and ‘screen.’ I find it delightful that this very visual work thus abounds in sound: “charnel carnations, carrion incarnate.” Can you speak of the relation of sound between page and screen and in Between Page and Screen? Between glyph and mouth, “text’s fleshy network.

AB: Sound is important to the exchange between P and S in part because of its playful, bantering quality—they are teasing one another through oblique references and sending coded romantic messages. As you suggest by pairing glyph and mouth, sonic play is also important to the book because in poetry sound is historically the place where language comes up off the page and reconstitutes itself in a reading body. It situates the poem as a performance in the reader’s mouth or mind’s ear. I think of the text’s mouthiness as an extension of the book’s concept—it takes shape in the space between media bridged by the reader’s body.

GB: Authorship. Othership. The book makes us think about the role of the reader, but it also engages with notions of the writer. Not only in terms of the interaction that is possible between reader and text, but in terms of the collaborative aspect. The ‘writers’ here include a programmer. The book makes me reflect not only on the implicit expectations of the traditional codex, but also the “programming language” of the traditional book: the various design, printing, and production technologies and the involvement of others beyond the one who comes up with the text.

AB: To take a page from the book, the word “author” comes from an Indo-European root (“aug-“) that means “to increase.” The writer has always augmented reality. I feel that in true collaboration the work could not take shape without the contributions of each party—each increases the work in some way, an auxiliary authorizing the other’s risks and inaugurating their own. An author is an augur who sees ahead to what the work might become, and with more than one, the text’s capacities continually wax. For Brad and I, sharing authorship was surprisingly intuitive, since the authorial role here so clearly extends beyond the content and into the material and digital affordances that amplify the work’s meaning. To be fair, we each had a task, something to create, but what we desired most was increase. It’s the reader, of course, who opens up that crease.

Amaranth Borsuk is the author of the chapbook, Tonal Saw (The Song Cave, 2010); Handiwork (Slope Editions, 2012), selected by Paul Hoover for the 2011 Slope Editions Book Prize; and, together with programmer Brad Bouse, of Between Page and Screen (Siglio Press, 2012), a book of augmented-reality poems. Her collaboration with Kate Durbin and Ian Hatcher, Abra, recently received an Expanded Artists' Books grant from the Center for Book and Paper Arts at Columbia College Chicago and will be issued as an artist's book and iPad app in late 2013. She has a Ph.D. in Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Southern California and recently served as Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in the Humanities at MIT, where she taught classes on digital, visual, and material poetics. She is an Assistant Professor in Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at the University of Washington, Bothell, where she also teaches in the MFA in Creative Writing and Poetics.