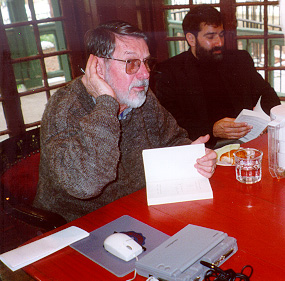

Note: Robert Creeley was a Kelly Writers House Fellow in April 2000. I conducted a public interview and moderated a discussion on April 11 before an audience of eighty people. The recording (both video and audio) of the interview has been available both on the Kelly Writers House site and at PennSound. Recently Michael Nardone transcribed it. We expect to publish the entire transcript in Jacket2 before too long. Meantime, below we present the portion of the discussion in which I ask Creeley about William Carlos Williams.

Al Filreis: Now back to Williams, your initial response to Williams — according to something you said at Camden in December [1999] — was that what mattered to you in reading Williams, particularly The Wedge, was that the work was driven by anger. This is what, at least, Ron Silliman posted to the Buffalo poetics listserv afterwards. And then he went on to comment on how Williams had a huge impact on him as well, but it was a very different Williams. So, if anger is not quite operating as much, what’s your Williams now? How does Williams animate you now?

Robert Creeley: Back to Ron’s point, that that wasn’t the Williams he read, he reads the later Williams.

Robert Creeley: Back to Ron’s point, that that wasn’t the Williams he read, he reads the later Williams.

Filreis: The Desert Music.

Creeley: Yeah. Which is not an unangry poem, so to speak. But it certainly isn’t nearly as angry as the poems he was writing in the thirties or twenties. Spring and All, for example. Or The Descent of Winter, or “March First.” Many of the early poems are really angry, and their emotional base is their revulsion and anger at the world he finds around him.

Filreis: So, now when you look back at Williams, how does it feel?

Creeley: Well, it feels very much like my own life. I, when young, felt a dismay, let’s put it, that such things as the Holocaust or the Second World War or the Depression or many other factors in one’s real life, that these could be so unremarkable to the body politic, that it seemed not to matter.

Digitizing Creeley's reel-to-reel tapes

Will Creeley sent us at PennSound this great note after hearing a PoemTalk episode about one of his father's poems:

I saw word of this latest episode via PennSound's excellent & useful Twitter feed, and figured it was a good opportunity to say thank you again to Al, Charles and everyone at PennSound & Kelly Writers House for taking in our big cardboard boxes and digitizing the reel-to-reel recordings inside with such care and precision.