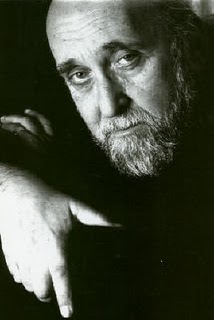

Jerome Rothenberg, 'A Paradise of Poets'

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

Bob Holman spent a few hours away from the at-times paradisal Bowery Poetry Club to help us (PoemTalk regulars Jessica Lowenthal and Randall Couch) figure out what sort of beloved community Jerome Rothenberg had in mind when he wrote his possibly programmatic poem, “A Paradise of Poets.” He published this short poem in a volume called Seedings and only then, a little later, published the book called A Paradise of Poets (which lacks the title poem). Confused? Please don’t be. The poem is a working out of the major preoccupying themes of the book that followed.

Bob Holman spent a few hours away from the at-times paradisal Bowery Poetry Club to help us (PoemTalk regulars Jessica Lowenthal and Randall Couch) figure out what sort of beloved community Jerome Rothenberg had in mind when he wrote his possibly programmatic poem, “A Paradise of Poets.” He published this short poem in a volume called Seedings and only then, a little later, published the book called A Paradise of Poets (which lacks the title poem). Confused? Please don’t be. The poem is a working out of the major preoccupying themes of the book that followed.

And what a book it is! In A Paradise of Poets we re-visit Paradise…err, sorry…Paris, where the ghosts of JR’s modernist forebearers (the generation of 1910, he says) appear to him in the guise of Left Bank street people, well dressed but destitute. He anticipates his own demise; he is lonely yet surrounded by the voices of poets he admires. And he realizes that a paradise of poets is only possible when one poet’s line stops just as the next poet’s line continues, a “line” indeed, as in lineage.

Bob, Jessica and Randall agree in our discussion that this is a heartfelt conclusion and that it must come in stages, beginning with the sort of poetic narcissism under the spell of which the poet believes that no one else can write his poem, even as he is writing over (literally on top of) that of his predecessor.

The world will not end when he does.

Asserting the centrality of such connectedness, Jerome Rothenberg, it was said by Allen Ginsberg, saved us all twenty years. Or, as Bob Holman put it, “He was Google before there was Google.”

May 28, 2008

No place for little lyric (PoemTalk #2)

Adrienne Rich, "Wait"

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

When Adrienne Rich wrote the poem "Wait" she and many Americans and others were awaiting the start of what seemed an inevitable war in Iraq, in March 2003. The PoemTalk crew - Jessica Lowenthal, Linh Dinh, Randall Couch and your convener-host Al Filreis - couldn't wait (as it were) to get going on this terrestrial poem. Is it a personal is political poem? The soldier, after all, looks at his or her wedding ring and thinks about why s/he wasn't told...but not told what? Is it a make love, not war poem? Is it a political poem at all? The Iraqi desert is "no place for the little lyric." The gang variously wonders if the poem had something large to contend about lyric's talent for reminding us of reasons why war is inhuman? Randall thinks it isn't much of a war (or antiwar) poem; its strengths diminish as it gets more clearly into its political subject; in the end it closes off "with a click." Linh prefers a less formalistic approach. Jessica and Al riff on the 1930s-style "hobos in a breadline" genre: its reputation for conservative form carrying radical content. Is this a formally conservative poem? If so, there's an irony, for sure. The PoemTalkers can only agree that such a question is open, making the poem all the more interesting (and in that sense it's a meta-poem, a poem about the problems of political poems).

PennSound's collection of Rich recordings offers downloadable mp3's of three reading, including her 2005 performance at the Kelly Writers House, where she read a bit from The School among the Ruins: Poems 2000-2004, including "Wait". She also gave a 32-second introduction to our poem.

PennSound's collection of Rich recordings offers downloadable mp3's of three reading, including her 2005 performance at the Kelly Writers House, where she read a bit from The School among the Ruins: Poems 2000-2004, including "Wait". She also gave a 32-second introduction to our poem.

Wait

In paradise every

the desert wind is rising

third thought

in hell there are no thoughts

is of earth

sand screams against your government

issued tent hell's noise

in your nostrils crawl

into your ear-shell

wrap yourself in no-thought

wait no place for the little lyric

wedding-ring glint the reason why

on earth

they never told you

PoemTalk #2 was recorded in Studio 111 at the Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing, produced by Al Filreis and Mark Lindsay. Steve McLaughlin was our sound editor and we had help from that talented soundhead, Curtis Fox. We're grateful to Adrienne Rich who agreed, when she visited in '05, to recite "Wait," a favorite of the Writers House-affiliated students.