Allen Ginsberg sings Blake's 'The Garden of Love'

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

Hear the voice of the bard…

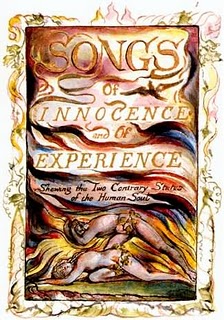

Which bard? Well, we’re not quite sure how bardic Charles Bernstein is, but he certainly loves the idea of poem as song; he jouned some by-now regular PoemTalkers (Rachel Blau DuPlessis and Jessica Lowenthal) and chanted for us that very line. We’ve worn the grooves on an old LP of Allen Ginsberg signing William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience and for the fourth PoemTalk chose Ginsberg’s countrified (crossover?) rendition of “The Garden of Love.” Does the snappy, twangy (and relatively tuneful) setting create an irony? Jessica thinks yes; Charles thinks no.

But perhaps the tune should be in conflict with the poem’s sense, and thus perhaps Ginsberg was not so much pushing a song of experience into a popular (and thus single-direction-tending) mode so much as making it still more Blakean.

The binary of innocence and experience, Rachel says, is broken by the way the song is sung. Blake wanted the binary to be broken; Ginsberg only breaks it further. And seems to be having fun along the way.

Listen for the happy out-take at the end. We had some fun ourselves, albeit somewhat atonally and quite arhythmically.

March 3, 2008

Romantic & Neo-Romantic Poems

New Audio Available

On October 7, 2009, Jerome Rothenberg and Jeffrey Robinson, editors of the third volume of Poems for the Millenium, came to the Writers House, gathering some friends and colleagues - and we all put on a show: readings from the anthology of romantic and post- and neo-romantic poems. The readings ranged from Black to Heine to Whitman to Perelman.

Now we (thanks to the talented Anna Zalokostas) present a fully segmented set of recordings from this event.

Download some romantic poems to your iPod this holiday and listen while you shop or while you drop.

Here is a link to the PennSound page, and here, below, are the segments described:

Jerome Rothenberg and Jeffery Robinson reading "The Ancient Poets" and "The Voice of the Devil" from William Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell; "Athenaeum Fragment 116" from Friedrich Karl Vilhelm von Schlegel; "To Richard Woodhouse, 27 October 1818" from John Keats; an excerpt from Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Aurora Leigh, Fifth Book; and "An Archaic Torso of Apollo" from Rainer Maria Rilke (11:51)

Charles Bernstein reading a poem after Edward Lear's "The Old Man of Whitehaven"; CB tr. of an 1847 poem from Victor Hugo's Les Contemplations; "The Ballad of Burdens" from Algernon Charles Swinburne; CB tr. of Heinrich Heine's "Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht" followed by poem after "Der Tod" from Shadowtime; his own "The Introvert," after William Wordsworth's "The Hermit"; excerpt from Walt Whitman's "RESPONDEZ!"; CB tr. of Charles Baudelaire's "Enivrez-vous": "Be Drunken"; William Blake's "The Sick Rose" from Song of Experience (12:12)