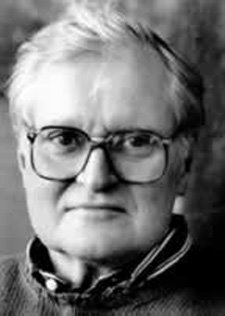

John Ashbery, 'Crossroads in the Past'

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

Our PoemTalkers — this time, Gregory Djanikian, Tom Devaney and Jessica Lowenthal — gathered to talk about a late poem by John Ashbery, “Crossroads in the Past,” from his book Your Name Here (2000). Amid the usual Ashberyean ontological bounty, here’s a poem that disentangles the crossed lines of narrative middles and ends (and beginnings). Straightens things out, or at least imagines the goodness of such straightness. And indulges in a nostalgia for the way things were at the start.

Our PoemTalkers — this time, Gregory Djanikian, Tom Devaney and Jessica Lowenthal — gathered to talk about a late poem by John Ashbery, “Crossroads in the Past,” from his book Your Name Here (2000). Amid the usual Ashberyean ontological bounty, here’s a poem that disentangles the crossed lines of narrative middles and ends (and beginnings). Straightens things out, or at least imagines the goodness of such straightness. And indulges in a nostalgia for the way things were at the start.

Is it age — or the loss of a loved one — that draws an anti-narrative poet to beginnings at the end? That, in short, is the question we posed of this poem. And does such a thing undermine a career-long devotion to middles with implied pre-stories? The wind blows in the direction it blows, and can’t be “wrong.” What about a “relationship”? Can — or should — a relationship be talked back to its beginnings, a narrative housecleaning?

Jessica and Greg decided finally that the apparently definitive ending dead-ends in an obvious imagery and sentiment. Tom and Al disagreed, seeing the poem as thus a meta-poem: a poem about the poet who has reached a point where he must re-imagine “the beginnings concept” and who realizes its failure.

Jessica and Greg decided finally that the apparently definitive ending dead-ends in an obvious imagery and sentiment. Tom and Al disagreed, seeing the poem as thus a meta-poem: a poem about the poet who has reached a point where he must re-imagine “the beginnings concept” and who realizes its failure.

John Ashbery read this poem as a Kelly Writers House Fellow in the spring of 2002. We have video recordings of the reading and an interview/conversation moderated by Al Filreis.

August 13, 2008

Gregory Djanikian, 'Dear Gravity' (2014)

The man in the middle, in the book The Man in the Middle, published thirty years ago this year (1984—a year before I first met this man in the middle), is a guy who managed to find his way out of the tower of Babel, despite the Babel of languages, French, Arabic, Armenian, broken English, buzzing in his ears from his immigrant refugee-ish elders.