Time's loop

A review of 'Möbius Crowns'

Mobius Crowns

Möbius Crowns

everything takes form, even infinity

— Gaston Bachelard

Near the end of the second chapbook of Möbius Crowns, a collection of aphorisms about the creation of the book, a bridge is constructed between poem and world:

Every poem walks toward the last line that abuts the margin, the margin abuts the hand that holds it, and the hand, having put the book down, might shadow the eye from the sun looking east across the lake or look west against the mountains.

Letters move from one to the next to form words; words move from one to the next to form lines; lines move from one to the next to form sonnets; sonnets move from one to the next to form this book that is read somewhere in the world, perhaps next to a lake or underneath a mountain. The location where the book is read is not predetermined. But that location exists by necessity, and the poems of the book will become poems of the world as they are read.

I read this book in Istanbul on a balcony on the fourth floor of a building with a glimpse of the Marmara Sea.

Before one experiences the aphorism announcing the connection between poem and world, one experiences a box.

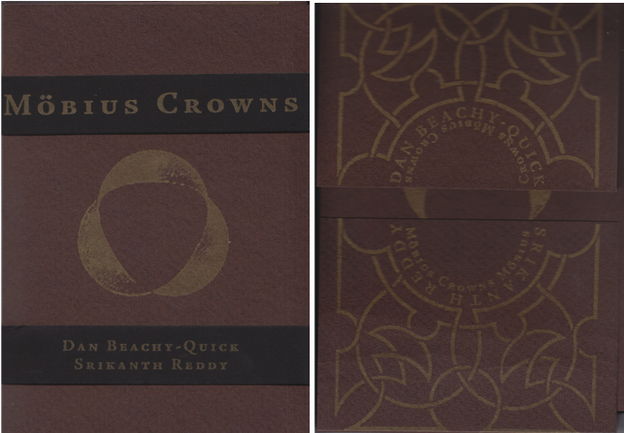

The form of this book is a box, held together by two thick paper bands. The top band says “Möbius Crowns.” The bottom band says “Dan Beachy-Quick / Srikanth Reddy.” Between the bands on the front of the box is an image, the design of a Möbius strip in gold, viewed from above. When the bands are slid off, the box opens up. It opens up fully, flattens itself against the table into a shape loosely resembling a bird or a specialized paper airplane. Three objects are inside the box. A single card and two chapbooks. The top chapbook is titled Möbius Crowns and the second chapbook is titled with the image of the Möbius strip.

As I read the book, the pieces that make up the book surround me. The box flutters gently in the wind that comes from the direction of the sea. I put the card inside the second chapbook to keep it from blowing away. I turn the spine of the second chapbook toward the wind to keep the book from becoming flattened open permanently.

The first chapbook contains poems. Each page is a separate poem and each poem is in the form of a sonnet. The first chapbook has two beginnings. There is no front and no back. Each side of the book is a separate entryway into the book. The first beginning is:

A sapling in a circle, roots buried

In air.

The second beginning is:

Now rages in the mechanism’s toothed gears.

In the first, a young tree suspended or growing upside down, exposing its roots to the air. Nature, though a nature that is distorted or, more likely, isolated — a tree without its earth, surrounded by a circle. The second of mechanics, equipment. “Now” is a noun, not an adjective of time — time itself. Now rages in the toothed gears. An eternal now raging forth in a cyclical motion, through the equipment of gears.

Wikipedia describes a Möbius strip as “a surface with only one side and only one boundary component.” This does not sufficiently describe what a Möbius strip is. The object looks similar to a ring, but a ring with a twist. A Möbius strip can be formed by taking a band of paper and attaching one end to the other with a half-twist. This twist turns the two-sided strip of paper into a one-sided loop. In a traditional ring, a single revolution around the ring brings one back to the starting place. In a Möbius strip, however, a single revolution from a point leaves one on the opposite ‘side’ of the surface. Without changing sides, one has moved from outside to inside or inside to outside. A second revolution is required to return to the starting point. During these two revolutions, the entirety of the surface is encountered without crossing an edge.

More than the sea, I see a succession of buildings as I read. Somewhere in the middle I hear the call to prayer, which bounces around the buildings, arriving as a multiple voice.

The question of form invokes the question of natural and artificial. Does something being made, being placed into a form, changed from one form into a new form, necessitate that it is artificial?

Bring me my coronet of rotating gears.

Contrive me a throne from coiled spring.

The throne is not an artificial object made from the natural object of a tree. The throne is contrived from the already-contrived coiled spring. But the spring is presented here as a basic, natural object. This spring and this throne are for a queen who lives “in a clock by the sea.” If one were to live in a world that is a clock, a coiled spring would be a basic, raw material. Of course, we do not live in a clock-world. We live in a “real world,” a world made up of the natural — what the real world provides — and the artificial — what we make of the real world.

At what point does material move from natural to artificial? What amount of work or manipulation must be put in by a human to turn naturally occurring metal into an artificial object of a spring? Is the spring, which begins and continues to remain metal that is originated in nature and earth, artificial?

This spring and clock-world exist in a story told by old men who “know their old story by heart.” The words of this story are stored in the heart. Others are stored in the mind:

Memory occurs before the event

Etches its weight as nothing in the mind.

Words become physically realized objects as:

Graven letters distended by time

The granite mother emerges as moth

A century past.

As I begin reading, a narrow band of sunlight runs across the center of the balcony stretching across my thighs. As I read, my pants become hot, and I sweat a little. I rub the sweat from my brow to keep the beads from falling onto the page. Though I am hot, I drink hot tea to quench my thirst.

In “The Origin of the Work of Art,” Martin Heidegger examines the line that divides “creating” and “making”:

We think of creation as a bringing forth. But the making of equipment, too, is a bringing forth … But what is it that distinguishes bringing forth as creation from bringing forth in the mode of making? … [W]e find the same procedure in the activity of potter and sculptor, of joiner and painter.

Heidegger then visits the point that the Greeks “use the same word techne for craft and art and call the craftsman and the artist by the same name: technites.” This argument based on linguistics holds a basic fallacy:

… for techne signifies neither craft nor art, and not at all the technical in our present-day sense; it never means a kind of practical performance. The word techne denotes rather a mode of knowing. To know means to have seen, in the widest sense of seeing.

To bring forth, to make, and to create is to know, and to know is to see. And to see is to see a thing of this world. The ultimate question becomes what it is to see the self:

There is this matter behind my face. I

Cannot find a shape to describe it.

If I open my mouth will you look inside?

What shape is the I? The exterior of the body apparently does not suffice to answer this question. The exterior body is the form of the box, but what the object is is also what is inside.

The second book begins:

I twist myself, binding my beginning to my end, thus making of I an O.

The second book is concerned with asking the question what shape has the I of Beachy-Quick and Reddy become after the act of creating? For Charles Olson, form, creation, and the self are all part of a singular process:

Form is not life. Form is creation. It changes the condition

of men. It does not disturb nature. Nature, like god,

is not so interesting. Man

is interesting. (Olson, Collected, 355)

This process not only occurs of itself, it occurs irrespective of nature. The metal spring is still metal, nature has remained preserved. What changes is the queen, who now sits on a throne made of a spring. What changes is the essence of Beachy-Quick and Reddy, who begin as an ‘I’ and end as an ‘O.’ It is their condition that has changed in the process of writing these poems. And it is the condition of the reader that changes as the poems are read.

Would it be so radical to claim that the sculpture or the painting is an object of the world? These objects are fetishized, often selling for millions of dollars. People travel around the world to look at these objects, and in some cases to possess or touch them. The object-ness of the visual arts is firmly entrenched in the art-ness. They remain inseparable, even in this age of mechanical reproduction.

The poem does not carry this same object-ness. The poem, rather, has historically assumed itself a more eternal, infinite existence:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade

Nor lose possession of that fair thou owest;

Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou growest:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this and this gives life to thee.

The lines of the poem give the possibility of eternity to the subject through the poem’s own eternal existence. Is this a reference to the ability to reproduce the words systematically in a way that only recently could be done for visual art? Permanence can be found in the non–object-ness of the poem, which like Shakespeare can transcend time and avoid the inevitable erosion of time, as happens to the statue in Shelley’s “Ozymandias.”

But the eternal and infinite of Möbius Crowns differs from the eternal and the infinite of Shakespeare and Shelley. Words are objects, not metaphysical, ephemeral entities. A word must exist in a physical realm, as an etching on stone, ink on paper, sound waves in the air, or neural synapses in the brain. Mother etched into the tombstone over time gets worn down to moth. Words that are read are made into physical entities that abide by the laws of physics. Words do not exist perpetually in an unchanging bubble that avoids the effects of time. Books must be reprinted as the old volumes age, crumble, and turn to dust. Printing and spelling conventions change, requiring updated, edited editions. The living language develops, leaving some words behind and creating new words. A work, even in its ability to pass through time, is also affected by time.

But there is an infinite at work in Möbius Crowns. Each page offers a sonnet. The succession of sonnets continues into the center of the book, where there is a juncture. The two sonnets at the center are upside down from one another, each appended with:

∞

The mark of infinity. Infinity does not necessarily encompass everything; it is not boundlessness or eternity. It can be limitlessness within a system. The book Möbius Crowns is infinite within its own boundaries, endless within its own form. The sonnets are not end-points. Each is a gentle curving back into the book from a different angle. From one center, a return to the front of the book and a delving in from the other side. Two loops through the book are required to return to reach an end, to return to the beginning. Turning from one beginning to the second beginning, there is a sense of déjà vu. In the first sonnet from one entrance there is:

The earth a body the monster turned

Inside out.

The first sonnet from the other entrance contains:

Any house will turn itself inside out

In good time.

These echoes continue throughout the loop back in towards the center from a new angle. Each sonnet is both an arrival and a departure. We recognize bare outlines, remember vague images, but:

There is no arrival, only return to a location we forgot we’d been in before, as the sun marks the solstice, as the sun marks the equinox; we look up at it and see it by its own light: an outline the crown of its own heat blurs.

I read this last aphorism and close the second chapbook. I look up and notice that the sun has moved from above my left shoulder to behind my right shoulder. The balcony is now enveloped in shade, and the breeze cools me. I do not need to shade my eyes from the sun, but I find myself using the book to do this, as if putting it against my brow will allow me to see something further off in the distance that I couldn’t see before. I see so many more buildings out there.

Works Cited:

Butternick, George F., ed. The Collected Poems of Charles Olson: Excluding the Maximus Poems. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987).

Reviews of chapbooks by Dan Beachy-Quick and Srikanth Reddy

Edited by Michelle Taransky