A quiver of chapbooks

A review of 'New-Generation African Poets'

New-Generation African Poets: A Chapbook Box Set (Tatu)

New-Generation African Poets: A Chapbook Box Set (Tatu)

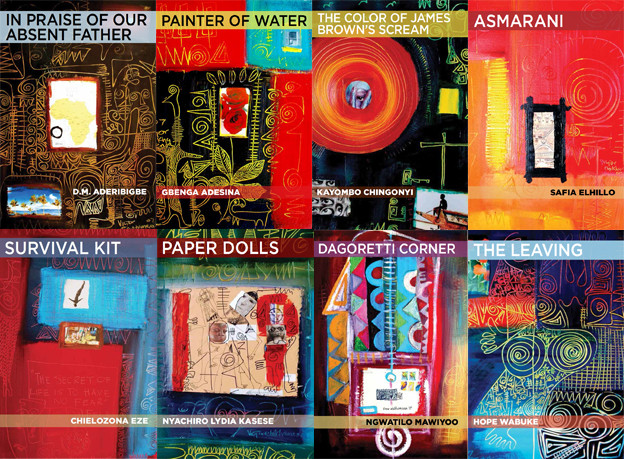

This chapbook box set is the third in an annual series, first published in 2014 by Slapering Hol Press and taken on by Akashic Books as of 2015. The box sets are a project of the African Book Poetry Fund, which also supports an impressive constellation of poetry prizes, poetry libraries in African cities, and book publishing — full-length collections by new poets, as well as collected or new and selected works by such major African poets as Ama Ata Aidoo, the late Kofi Awoonor, and Gabriel Okara. Having titled the first two sets Seven New Generation African Poets and Eight New-Generation African Poets, coeditors Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani were forced by the fact that this third iteration also features eight poets to settle the issue of naming. As Dawes puts it, “By tagging on to our new title the word tatu, a Swahili word denoting the number three, we are codifying our faith and confidence that this is truly a series.”[1] Indeed, the most recent set — Nne or four — was released this past April with ten more chapbooks, although they will have to await a future review. Each chapbook in the Tatu set bears a preface by an established poet, and each bears cover art by Victor Ehikhamenor, a Nigerian artist and writer who is currently exhibiting at the Venice Biennale and is increasingly in demand as a cover artist. While the box set is thus a quiver of gorgeous physical objects, the poetry itself is just as arresting as Ehikhamenor’s designs.

In language more familiar from the front of novels than poetry volumes, the copyright page of each chapbook declares: “This is a work of fiction. All names, characters, places, and incidents are a product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.” There is an unresolved tension between this boilerplate legal language and the manner in which poetry draws on histories — autobiographical, familial, and national — for its content. Countering the notion that lyric poetry necessarily represents “the action of a fictional speaker,” Jonathan Culler argues that “there is a crucial difference between treating the lyric as projecting a fictional world, with a fictional speaker-persona, and maintaining that the lyric makes real statements about this world, even though the relation of these statements to the experience of the author is indeterminate.”[2] My use of the term “the poet” below, then, is meant to index the fertile if uncertain ground between autobiographical “author” and fictional “speaker.”

Both “real statements” and their indeterminate relation to autobiographical experience are on display in Chielozona Eze’s Survival Kit. Eze is the most experienced author in the set, a professor in Chicago who has published three academic monographs and a novella, and Survival Kit is the most substantial of the chapbooks at fifty-two pages. It consists of five movements, each focalized through a figure, “The Migrant” or “The War Survivor,” based on Eze’s own history as a survivor of the Nigerian-Biafran War (1967–70) who migrated to the US. Poems returning to the Nigerian-Biafran War form the literal and metaphorical heart of the chapbook in the sections “The Migrant Looks at Pictures of the War He Survived” and “The War Survivor Talks with His Memory.” Later poems, in one of which the poet offers another memorable figure of himself as “Afro-vagrant” (43), probe injustices in other parts of the continent, from apartheid legacies in South Africa to homophobia in Uganda. Abani’s Preface presents Eze as “a true and worthy successor of Christopher Okigbo” (10), the leading Afro-modernist poet who died fighting for Biafra, yet Eze’s tone is less hieratic, more conversational. The end of “Before Death, Hell” sums up the poet’s recurring emphasis on this-worldly rather than otherworldly salvation:

Hell comes after death, said the preacher.

But I’ve been to hell.

Thirty months long.

And I’ve learned to love the earth,

deficient as it is,

thirty times better than heaven. (25)

Hard-won grace is a hallmark of this suite of poems.

The two younger poets from Nigeria in the set, D. M. Aderibigbe and Gbenga Adesina, draw attention to the worldly attachments that survive violence in the poet’s family and in Nigeria’s northeast, respectively. In her preface to Aderibigbe’s In Praise of Our Absent Father, Tsitsi Jaji places his “voice,” which is largely concerned with the travails and small triumphs of the poet’s mother and grandmother, “in the tradition of male Nigerian feminists” (7). The title also places the chapbook, albeit with some irony, in a tradition of Yoruba praise poetry, or oríkì, mentioned in “Ode to My Grandmother’s Mouth” (“she sang my cousin’s Oriki” [31]). In the title poem, the poet’s mother “wore / aso-oke — she danced, we ate — / raising cups in praise of her loneliness” (22). The absent father is addressed in the next poem, “Missing”: “Father, / you wrote a story on my mother’s / skull with a corkscrew // before leaving for Milan” (23). Alongside Aderibigbe’s sensitive portrait of domestic violence and women’s resilience, Adesina’s Painter of Water portrays the violence and victims of the Boko Haram insurgency and military counter-insurgency, including such catastrophes as the killing of Buni Yadi schoolboys and kidnapping of Chibok schoolgirls in 2014. The chapbook intersperses unhurried, evocatively long-lined poems with shorter-lined near-sonnets of ten to thirteen lines, including the title poem. In a departure from much previous Nigerian poetry’s urgent railing against “khakistocracy,” Adesina depicts the humanity and vulnerability of soldiers, whether the little girl’s “soldier dad” in “Ceasefire” (10), the “young soldiers” crying in the poem of that title (13), or the soldier who could not be at his mother’s deathbed in “How To Paint a Girl” (19). This is not to say, though, that his poetry harbors any sympathy for the Nigerian state or military. “Here in this room, under the dark governance of this night,” the poet waits in “Ceasefire” with his soldier brother and family, “wishing we were nothing but butterflies who have / no governments save the ones in their wings” (10).

In its exploration of rural struggles, Ngwatilo Mawiyoo’s Dagoretti Corner bears some resemblance to Adesina’s work; Mawiyoo undertook a project called This Kenyan Life, living with families in seven rural areas across Kenya, in part to confront ethnic stereotypes that contributed to violence following the December 2007 election. While violence lurks in the background of these poems, flaring into the foreground in “Benda, In the Rift Valley, January 2008,” Mawiyoo is equally concerned with the ethics of the poet’s quotidian relation to those she depicts. In “Research,” a poor rural mother gives her sole mug of whole milk to the visiting writer, rather than to her five-year-old daughter:

Twice

in ten days I took the cup

from her mother’s hand,

twice in ten days, mute. (13)

The crossing of class privilege and sustenance is slightly less agonized in the title poem. There, the poet declares, “I am always / on the edge of things” (23), as she plays up to middle-class expectations at a posh café before crossing the corner “to haggle for a week’s supply of fish” (24). Mawiyoo’s poetry is as formally restless as it is ethically searching. In addition to poems in regular and irregular stanza forms, the chapbook includes an ambitious sestina (“Postcolonial Blue”) and, seemingly reserved for the most grievous matters, prose poems. Of the latter, “Site of Sorrow,” memorializing the 2013 attack on the Westgate Mall, builds on an epigraph from “Songs of Sorrow” by Kofi Awoonor, the great Ghanaian poet killed in the attack, to gather to a haunting close: “Brutalized all, we weep in grief’s blasted cavity, our own echoes our comfort” (25). While the subsequent six-part prose poem about the poet’s father, a recurring figure in the chapbook, charts equally harrowing territory closer to home, the final, free verse poems slip into images of water and rebirth, as if to wash away not only blood, but also the Nairobi dust of the chapbook’s opening “Portrait.”

Hardiness in the face of personal, particularly gendered, violence, links Nyachiro Lydia Kasese’s Paper Dolls and Hope Wabuke’s The Leaving. Kasese, from Tanzania, deals in a series of poems, including the title poem, with sexuality and the consequences — grief, anger, shame — of breaching “Accepted Standards,” as one of her titles calls them. As the chapbook proceeds, the poems often deliver a surprising final line. “Bottomless Chasm” consists of only two: “We were traveling cross-country the other week. / Somehow I lost you in one of the valleys” (27). This striking couplet sets up the emotional climax of the chapbook, “Flowering,” in which the poet offers flowers — hibiscus, bougainvillea, tobacco — for horrific incidents of gendered violence and her own anger at such injustice before offering a prayer:

To my unborn daughters:

sometimes your mother will play apothecary,

and still her medicine will not protect you from the monsters under your beds. (29)

In Hope Wabuke’s poems, the mother-figure is a nurse, and yet neither can she protect the poet. The Leaving weaves a narrative of four generations, from the poet’s grandmother, for whom “my mouth is alien / foreign waters lapping at / a foreign shore” (34), to the poet’s infant son, by way of parents who fled Idi Amin’s Uganda for Kenya, then America, only to face a racist reception in the Midwest. Every poem title is connected either with an aspect of the body (e.g. “Mouth,” “Skin V: Four Years in Evanston, IL,” “Spine”) or with the Hebrew Bible (e.g. “Exodus: Father’s American Superheroes,” “Leviticus,” “Naomi”). In “The Chronicles (of a Violence Foretold),” perpetrators of violence — white Midwestern neighbors, Ugandan soldiers, the poet’s and her sister’s boyfriends — are confined to no one place or identity. Wabuke, who teaches at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, calls out ongoing racist violence in the US, as in the final poem, “Letter to my Son IV: Hips,” when the poet tells her child that on the day of his birth,

I held your soft warm realness and wished you safe

again inside instead of this place

and you the target for white folks’

stand-your-ground black boy hunting. (38)

Chris Abani observes that “[s]ome of what it means to be a modern African has been shaped by conversations started in the diaspora,” from slave revolts to the US Civil Rights Movement. [3] Wabuke’s poetic analysis of family, forced migration, racism, and life in the diaspora — “your glorious / tangled mess of becoming” (11), she terms it in the opening poem — contributes incisively to crucial twenty-first century conversations.

The final two poets in the set, Kayombo Chingonyi and Safia Elhillo, likewise have in common a visceral lived experience of diaspora. Each engages with a particular genre of music from the past, Chingonyi with UK Garage of the 1990s and early 2000s, Elhillo with the songs of mid-twentieth century Egyptian singer Abdelhalim Hafez, in order to take lyric to unexpected places. In The Color of James Brown’s Scream, Chingonyi, who was born in Zambia and has lived in the UK since childhood, offers some of the most sonically intense work in the set. In the heavily enjambed couplets of an early poem, “Martins Corner,”

Meat wagons sing an ode in sardonics

passing a bus held briefly to regulate

the service. Jesus loves you, if you

believe in signage. High heels clack,

are slung off, taken in hand. […] (12)

The synesthetic title poem addresses the DJ Larry Levan (1954–92) as the Vodou god of the crossroads — “Teach us to shape-shift, Legba” — and conjures a barman fixing “a drink our lips / will yearn for, a taste we’ve been / trying to recreate ever since” (21). “Self-Portrait as a Garage Emcee” recreates in ample detail a now-faded constellation of radio and cassette tapes that led the young poet to Garage. Initially a refuge from racism in “the white-flight-satellite-town we moved to” (22), music, the poet learns, is not immune from the politics of race: “Eminem ruined everything,” as “no amount of practice could conjure pale skin and blue eyes” (27). A pair of poems later in the chapbook, “25th October, 1964” and “Curfew,” reach even further back to recreate the post-independence Zambia of his older relatives. The chapbook closes with a love lyric imagining a place where “the past is an old song / nobody knows how to sing anymore” (33). Chingonyi’s poetry certainly does know how to sing, and his first full-length collection, Kumukanda, was published this summer in the UK by Chatto & Windus.

Safia Elhillo is “Sudanese by way of Washington, DC,” in the words of her bio, and much of Asmarani works through the poet’s relationship to Arabic as well as English — “i have an accent in every language” (20) — by way of a poetic relationship with Abdelhalim Hafez, who died before Elhillo was born. In “why abdelhalim,” the poet answers the implicit question of the title by emphasizing parallels between poet and singer:

he belongs to no one country [same]

he belongs to no one language [check my mouth] (28)

As for why Asmarani, Elhillo explained in an interview last year that “many of Abdelhalim’s songs are addressed to ‘al-asmarani;’ asmarani is a term of endearment in Arabic for a brown-skinned or dark-skinned person. Right from the start I was struck by how radical it was to specify a darker girl in a culture (and a world, really) marked by colorism and antiblackness.” As the politics of accent, skin color, and hair thread through the chapbook, so too do bodies of water:

no language has given me

the rhyme between ocean &

wound that i know to be true (27)

The association between water and wounding stems in part from Abdelhalim’s death from complications relating to a water-borne disease he contracted as a child. But this “rhyme” is also that of diaspora, a physical and more metaphysical ocean separating family in the US and in Sudan. Exuberant and serious, experimental and approachable, Elhillo’s poetry makes inventive use of white space, Arabic script, brackets, and found text. Intrigued? You can find Elhillo’s poems not only in this chapbook set, but also in her recently released full-length collection, The January Children.

Who, then, are new-generation African poets? In his introduction to the first chapbook set, which included poets living in Botswana, Kenya, South Africa, the UK, and the US, Dawes observed that “Africans, like everyone else in this migration-crazy world, move,” and concluded that all the poets promoted by the project “self-identify as Africans in the full and complicated way that Africanness is best defined.”[4] “New-generation” may be a less fraught but equally fuzzy term. The concept of a literary generation is at once nearly indefensible and nearly irresistible for critics. Nigerian literature, for instance, is often classified into three generations: a first generation of writers identified with decolonization and independence, such as Christopher Okigbo and Wole Soyinka, a second generation of those who came to prominence after the Nigerian Civil War in the 1970s, and a third generation who began writing during the military dictatorships of the 1980s and 1990s. But are those who started publishing in the 2000s part of the third generation or a fourth (or fifth)? What about a poet such as Eze, who experienced the Nigerian Civil War but did not publish a book of poetry until recently? And how might this schema work for a writer from Tanzania or Uganda? The “new-generation” tag avoids the need to answer such questions. In effect, it means that although at least two of these poets had published a chapbook before, they had yet to publish a full-length collection. Fortunately for students of poetry, African writing, and our contemporary moment, that is quickly becoming no longer the case.

1. Kwame Dawes, “An Introduction in Two Movements,” in New-Generation African Poets: A Chapbook Box Set (Tatu), ed. Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani (New York: Akashic Books, 2016), 13.

2. Jonathan Culler, Theory of the Lyric (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 2, 107.

3. Chris Abani, “An Introduction in Two Movements,” in New-Generation African Poets: A Chapbook Box Set (Tatu), ed. Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani (New York: Akashic Books, 2016), 14.

4. Kwame Dawes, “An Introduction in Two Movements,” in Seven New Generation African Poets, ed. Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani (Sleepy Hollow, NY: Slapering Holl Press, 2014), 5, 8.