The new ground still remaining

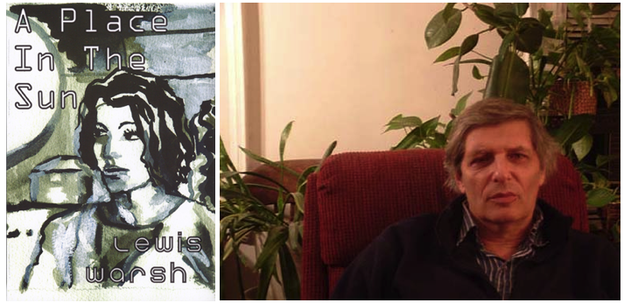

A review of 'A Place in the Sun'

A Place in the Sun

A Place in the Sun

Lewis Warsh's A Place in the Sun hopes to be called pulpy. It earns the title twice — with its breakneck story pacing and with its subjects (beautiful New York Russian women and the cops/criminals in their lives). The pulp angle on pace and structure is the far more interesting of the two. This is where the book genuinely succeeds, and where Warsh points to the new ground still remaining in experimental prose.

The collection winds through six stories. From story to story the subjects shift wildly, but the same pressures distill them all: rote storylines are forced through the excesses of their campy renderings to come back around to a new kind of clarity.

In The Russians, a story that ticks through a half-dozen perspectives on New York immigrant life, a violent kitchen break-in binds the characters (named Eddie Perez Irene, Marina, and Ivan, and rendered flat as paper dolls). In Secrets, the melancholy of contemporary writing life is exaggerated, to excellent effect, playing off writing-program sexy-intrigue as a desperate cliché. Warsh pushes the cliche to noir-trope in its extremity:

People think I'm an attentive listener but the only reason I talk to them is to use what they say in my writing. … Maybe you'll recognize yourself in my stories, maybe not. Maybe everybody's stories are the same. Teeth. Everyone has problems with their teeth, but those aren't the stories I'm interested in.

The title story A Place in the Sun is especially surprising and wonderful. In hollow gossip-rag tones we walk through a love affair so overblown, it swells to fill its own Hollywood frame, and only Monty Clift and Liz Taylor could fit: “Elizabeth shared a room with her mother but Monty often coerced her to stay out late at night. They would sit on the wooden steps of the hotel and stare at the moon.”

As the stories progress, their exaggeration and commitment to surface could estrange the reader. But dream-cycle structures begin to coalesce and draw the stories together into a whole. A Place in the Sun is surprising to read, staying stubbornly flat while remaining compelling, refusing the easy routes of ironic mocking or deeper characterization and instead offering only a willingness to move forward with the reader. It is structure and experiment that carry the book, while noir signs float freely on the surface.

Still, the style is prominent and the way Warsh deploys details raises questions about how mysteries and noir so often shape the content of prose experiments (Joyelle McSweeney's Flet, Chris Kraus's Summer of Hate/Catt: Her Killer, all the way back to George Perec's La disparition). How do these tropes stay powerful?

There is an element of wishful thinking, or willful sentiment, in the experimental noir retread. Consider the word “gumshoe,” an awkward relic, more apt in a book reviewers' critical air quotes than in reportage or sincere dialogue. The topic remains utterly relevant: the drama of characters living at the edges and the high energy potential of all cop encounters will keep fueling work for a long time to come (as they do in beautifully considered recent work such like Methland by Nick Reding, The Wagon by Martin Prieb, Another Bullshit Night in Suck City by Nick Flynn, the whole phenomenon of The Wire). But it’s the borrowing of style, not the interrogation of the subject matter that has become a mainstay of prose experiments. It's possible that there is a pragmatic reason for this transfer. Noir language offers a register that is already strange to a contemporary ear — expecting an outdated lexicon with its own cute idiomatic expressions, the reader's ear is primed for the stretched and pummeled language of experiment.

But A Place in the Sun also points to the artifice — and silliness — of this heightened nostalgia. Our false familiarity always focuses on the memory of a universal draw. Force-styled fiction works on the kind of slipped memory used in pulp erotica images, proliferating now in band posters, vodka ads, and a Robert Downey Jr.'s Photoshop meme, poignant because this brand of paper-text erotica is long extinct. The ghost accessibility of noir tropes are likewise outdated for any primary use, but signal back to an awareness of a memory of their own styling — private eyes, tender cops, hardened lovely ladies, cabs, rain, fog.

These conventions have outlasted their accuracy, but the narrative pull and pleasure of most genre pacing has not. So why do prose experiments so often borrow details and leave the pace? Why is the joy of attention, of being held by a text, a force so infrequently put to work in experimental fiction? A Place in the Sun asks to be used as a departure point for better manipulation of pace and absorption, even as it so enjoys its own surfaces.