A lot of things happened

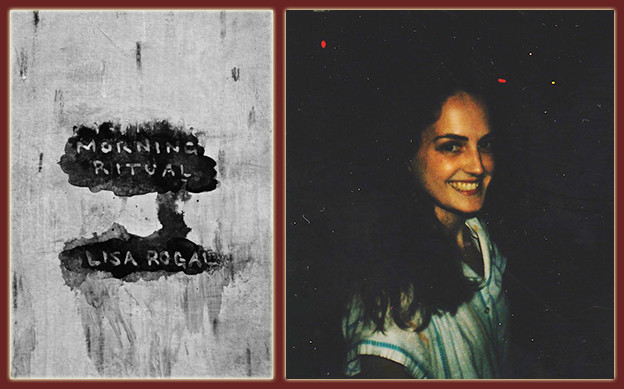

A review of Lisa Rogal's 'Morning Ritual'

Morning Ritual

Morning Ritual

The title of Morning Ritual superimposes the divine and the mundane: one thinks simultaneously of a prayer to greet the sunrise and of brushing one’s teeth. In this book, however, Rogal is firmly rooted in the quotidian: it’s toothbrushing that she’s interested in, and she resists the urge to give daily “rituals” like this more than their usual significance. What she shows us by doing so is that their usual significance, though minor, is nonetheless an essential part of the tapestry of our experience and worth exploring.

The opening piece, called “I woke up this morning,” is a series of alternative scenarios in which a frustrated tenant faces a plumbing malfunction. Most of them begin with these lines: “I woke up this morning and ran the faucet. It was the fourth day without hot water, and I wanted to kill my landlord.”[1] From here, the speaker wheels through a wide array of possibilities: in some scenarios, she tries and fails to fix the plumbing herself; in some, she goes for a run and tries to forget about it; in one, she goes sunbathing on the roof and runs into a hallucinatory dreamscape of nostalgia; and in one, she actually does kill her landlord. These are only a few of the alternatives, and the effect is like a splintering of time. At one point, the speaker contemplates the flow from her tap in a way that is suggestive of Rogal’s technique in this piece:

I woke up this morning and ran the faucet. I let the faucet run and run and the sound and sight of continual water turns into a trance. I keep inserting my fingers into the stream to see it ruined and restored over and over. I want to ruin it over and over forever and play with it to make it become other things. It insists on being water, on being movement and stillness at once, on coming forever though eventually it will end … (21–22)

This is the way time works in “I woke up this morning.” Rogal dips her fingers into the stream of time and interrupts it: the first sentence is definitively in the past tense, while the second begins with the ambiguous tense of “I let the faucet run” and transforms into the present as the “sound and sight of continual water turns into a trance.” In this piece, Rogal plays with possibility, letting all these alternative versions of the morning coexist in the present, even though only one will become the definitive past.

Rogal’s crafting of everyday experience into the stuff of poetry certainly owes something to modernists such as Gertrude Stein, as well as the Oulipian writers. The iterative technique of “I woke up this morning” brings to mind Raymond Queneau’s Exercises in Style, though Rogal’s style throughout this book is relentlessly plain and colloquial. One also thinks of Stein’s The Making of Americans, a book in which Stein claimed that she had created a sense of a “continuous present” by “beginning again and again.”[2] Rogal implicitly acknowledges another modernist influence:

I can’t help but be of two minds / three minds

like a tree / all white

no leaves to lose / no birds

some of these trunks smell like alcohol (86)

This is a play on the second stanza of Wallace Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”:

I was of three minds,

Like a tree

In which there are three blackbirds.[3]

Rogal’s version muddies what for Stevens was a crystal-clear image: for him, three distinct minds are like three distinct birds; for her, two minds blur into three, the tree is barren, and its relationship to the minds is obscure — and furthermore, somebody’s been drinking. Rogal’s project is not one of disciplined focus on crystalline moments; rather, not unlike Stein’s work, Morning Ritual exposes the difficulty of such focus and suggests that a wide-ranging and creatively distractible mind might be a more interesting lens on the world.

Furthermore, Morning Ritual’s epigraph from Georgia O’Keefe insists on duration rather than an instantaneous image: “Nobody sees a flower — really — it is so small it takes time — and we haven’t time — and to see takes time — like to have a friend takes time” (9). One poem titled “I’m talking” seems to track a series of conversation topics from the frivolous to the intimate, perhaps in demonstration of this point about friendship. It opens this way:

I’m talking nihilism

I’m talking botany

I’m talking television

I’m talking Nazis

I’m talking talking

I’m talking Vaseline

I’m talking glasses

two pairs for less (55)

It goes on like this for a while, before abruptly making a brief turn for the serious:

I’m talking cookies n’ cream gelato

I’m talking you

have a different experience

than me different reality

I’m talking yeah

isn’t it true and well

I have to reject interesting things though

they’re nice to think about

I’m talking look how far we’ve come guys

I’m talking bottomless hunger

I’m talking bottomless coffee

on Tuesdays (56)

Rogal transforms a conversation into a meta-monologue by reducing speech to its topics, and by leaving out the responses of the speaker’s interlocutor(s). The rapid-fire parts make the speaker sound a little like a used car salesman (“I’m talking four-wheel drive; I’m talking no money down”), and by extension make the conversation feel cursory, impersonal, and perhaps self-interested — but when the topic shifts from gelato to a reflection on experience and reality, the pace slows down and we suddenly hear the speaker’s actual voice as the conversation gets more intimate for a moment before returning definitively to the quotidian with the mention of “bottomless coffee.” Rogal shows us that it doesn’t necessarily take the intense focus of Stevens on a blackbird to elevate the quotidian into the significant, but that we all do it all the time. Shifts in register, focus, and intensity like these populate our everyday conversations and experiences, and are worth documenting in part because they are how we forge real connections with one another. By the end of the poem, the subjects of conversation have gotten quite intimate:

I’m talking empathy

and how we will unwind

I’m talking about the candles we burned to

the wick in the night

I’m talking space heater — space heater

fire because

we laid

our cold bras across it

I’m talking cupping warm mugs

your hands are freezing

I’m talking all these phrases

living with me

I’m talking a thing

you can’t escape

I’m talking Tahiti

close your eyes

to what you can’t imagine (58)

Here we have a literal and figurative thawing; the conversation that at first careened from nihilism to botany to television to Nazis is now focused on these moments of warmth and intimacy. The last few lines are a little puzzling: are the relatively grim far-indented lines part of the speaker’s monologue? The voice of the interlocutor at last? Some of the phrases that “live with” the speaker? The poem, like many in this book, resists neat closure, but it succeeds at capturing the texture of conversation: the shifts in topic and tone, from the mundane to the philosophical to the intimately personal, that make up our day-to-day connections to one another.

The final piece of the collection, “A lot of things happened,” acknowledges another explorer of the everyday: Georges Perec. The piece begins with what turns out to be a reference to his work: “A lot of things happened today. I mean, I feel I exhausted the day in some sense, seeing as I started it one way and transformed several times since then” (98). The speaker goes on to recount her day in comprehensive detail, which includes her picking up and beginning to read an unnamed book of Perec’s in which he is described as “[sitting] for three days in the café eating sausage sandwiches, drinking beer and coffee, writing, and just staring for long swaths of time” (112). The book must therefore be An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, in which this was precisely his project — to try to take notes on every person, object, event, and weather pattern that passed before his eyes over the course of three days of sitting in cafés in Paris’s Place Saint-Sulpice. Perec explained that in his book he wanted to investigate “what happens when nothing happens”[4] — and in the title of Rogal’s piece, we have her answer: “A lot of things happened.” The “things” that she describes are by definition not very monumental or even very interesting: she walks her dog, gets back a phone that she’d lost the night before, has sex with her boyfriend, picks up some books (including Perec’s), goes to a café to read them, and overhears some conversations there. At the end of this piece, which is the end of her book, the speaker has dissolved into Perec; she is reading his book while sitting at a café and observing the people and things around her just like he did. Furthermore, she explains how Perec himself dissolved: “He could see everything and nothing saw him, except through his own observations, imagining himself through his own eyes, a self-determined self, a solid self, documenting changes as they swirled around him” (112). In this final image, the act of observation empties out the self, and what causes it to become “solid” again is only one’s own imagining. What seems more real than “self” here is the tapestry of observations about the changing minutiae of the plaza. As Rogal vanishes into Perec, as her observations vanish into his, and as both speakers vanish into their observations, we learn that it’s the act of attention itself that may be more important than the details of Perec’s Paris or Rogal’s New York. We need not pretend that these details are fascinating in order for them to be worthy of our attention, for we live among them and they can always show us more about who we are.

2. Gertrude Stein, “Composition as Explanation,” in Writings 1903–1932, ed. Harriet Chessman and Catherine Simpson, (New York: The Library of America, 1998), 524–25.

3. Wallace Stevens, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Vintage, 1990), 92.

4. See Erik Morse, “An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris by Georges Perec,” Bookforum (September 24, 2010).