'If I lose you in the street'

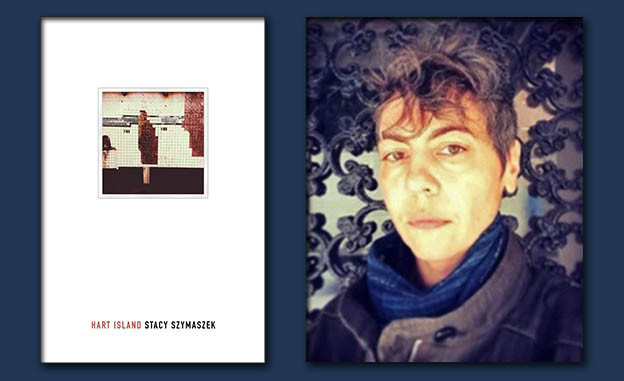

Stacy Szymaszek's 'Hart Island'

Hart Island

Hart Island

In Hart Island, there are whispers of people who lie just below perception, muttering multivocal protests of how, based on their status in life, they are placed away and forgotten, invisible shoulders upon which the city (or the poetry world) rests. Not an anxiety of influence, but a murmuring of both injustice and desire to connect, for recognition — for people to either stand at the grave and acknowledge or appreciate, no matter who a person might be or might have been. Toward that, Hart Island is part memory, but it is also active record of life taking place on the page, a liquid unfurling of how language apprehends the incomprehensible about it, as quickly as it takes shape and then dissolves again.

Just as Frank O’Hara’s words on a plaque placed to the side of the entrance to the Parish Hall of St. Mark’s Church shape the experience of poets about to enter for a reading, I hear his echo, particularly of his great poem “Second Avenue,” in Hart Island. There’s a similarly mercury-liquid pace of poets moving through urban space abstracted through language, a similar exploration of how concrete existence shared with so many million others changes through time and in that change is all the shifting states of consciousness of both here and not-here. Change is supposedly the opposite of death, but are those buried in Hart Island actually in that presumably static state when relatives and friends are not allowed to visit and meditate upon that still connection, when those buried are not publicly named and therefore definitely declared dead? Instead, it’s limbo: a suspended state of anticipated transformation. Szymaszek explains in a preface that Hart Island is the location of the largest tax-funded cemetery in the world and one to which public access is severely limited. So those disconnected from their dead are not able to move on, but yet they do — the paradox of never-ending mourning, or the myth of “closure.” And in the place of family and friends, those who tend to the plots are inmates of Riker’s Island, another island of injustice and erasure.

The yard of St. Mark’s Church is also a cemetery, and the poets who work and read there walk over a system of vaulted spaces and read next to wall spaces filled with dead people. Some poets’ ashes have also been sprinkled surreptitiously and illegally in the back garden (and that’s all the detail I’m going to give). While to imagine so is what’s called a “pathetic fallacy,” or giving life in verse to natural or inanimate objects, the walls yet seem responsive to the hundreds of readings given at the Poetry Project. Is it so pathetic to imagine that a certain kind of ongoing vibrational energy has been set up within the molecules that make up that plaster, paint, and brick?

Even so:

this veneer of civilization is

“[I have other skills?]” only recently

de rigueur for poets best not say

“[There are other workers]” you

work here sore groin stand-in

for black eye triggered

impulse for some cake you’re a big

lesbian wipe off your knees save cry

into wilderness for after dinner (44–45)

The heart of Hart Island and Hart Island might be about what it is to treat people, and bodies, decently, whether alive, dead, or an employee of the Poetry Project. How does identity extend from poet to citizen to denizen to worker to corpse? Szymaszek’s language is buoyant, expressive, perplexing, transforming, and at times almost desperate — again, like O’Hara — in how she trusts poetry to keep her alive and speaking through situation after situation. “Your distinction is merely a quill at the bottom of the sea,” writes O’Hara in “Second Avenue.”

But unlike O’Hara, the body and its travails intrude at odd, anguished moments and very unlike O’Hara, Szymaszek’s form is shorter, closer to speech, fragmented, quicker to turn, less enchanted with sound and sound for sound’s sake, or the sonic beauty of frilled lines.

elaborate sty in my eye

bisection of okra garden

is euphemism for flea

market necropolis so

if I lose you in the street

if I lose you in the street (33)

Her form is a different kind of necessary, more squeezed, more urgent, less conveying of influences (Rimbaud, for one) and more conveying of voices muted by gender, class, and race — perhaps M. NourbeSe Philip is another influence in listening for and providing voice to the dead, or Alice Notley, attempting to provide a conduit for those beings/nonbeings.

The layering of experiences within language is intense, and the entrances and exits to and from busy street to cemetery/yard to office to artistic space to all the other incessant and disconnected places of today like malls, stores, institutions, are as abrupt and as rich as in “real life.” Maybe Ed Roberson’s City Eclogue and how it layers all the human connections and histories of civil rights vital to a city is also a reference for Hart Island:

“involve body in muscle

memory” hit mailbox and

pharmacy veer away from

HRC kids who see easy fix

for marriage money no

grail collects the blood

via undressed living

space flush dirt from poor

tile job poorly tiled face

enter the yard where

everybody knows the sexton

is the saint (28)

But I don’t mean to imply that Hart Island is all influence. Quite the opposite: such a poem putting together this sort of language from this sort of perspective (even perspectives) is rare (but desperately needs to be less so) — the poet is a flâneuse, but one who is not a figure of leisure, nor a male who enjoys relative safety and privilege when moving through the city or institutional spaces to acquire them somewhat. And this acquisition often becomes monoperspectival — the flaneur edges toward the tiringly ubiquitous singularity of the hero. Instead, this working flâneuse observes from her stance below-radar and belowground the essential details of how space-institution-art-poetry world-cemeteries are built and made and maintained. And what’s more, shapes these tough and jagged facts and observations into poetry.

… I don’t know

why do you come here?

one night the gates were left

open and the people who were

sleeping continued to sleep (69)

Ultimately, while these final lines of Hart Island question that true change can really occur, I still find in the very difficulty and risk of writing such a piece, as she questions the order in how the poetry world is constructed and its previously unspoken hierarchies — questioning that rarely ends well for the questioner — a desire that change will occur, that the workers will be acknowledged and respected, that the dead will be named and visited, reestablishing the essential connections that keep the entire city (of poetry) afloat.