'I am the hydra of I / and soon I will be the next thing'

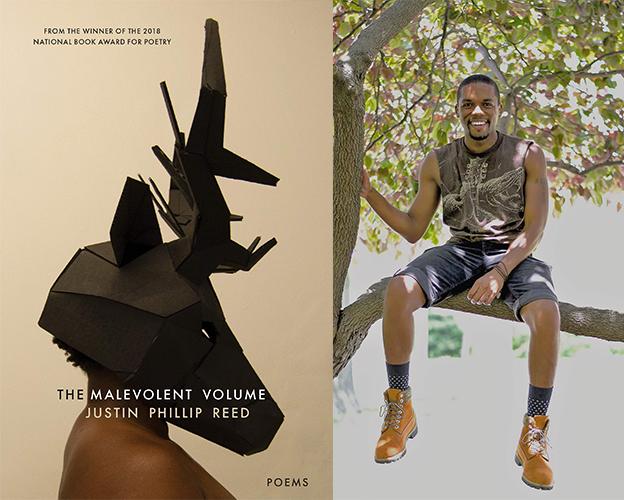

A review of 'The Malevolent Volume' by Justin Phillip Reed

The Malevolent Volume

The Malevolent Volume

Justin Phillip Reed’s second collection of poetry — following his 2018 National Book Award for Poetry–winning debut Indecency — is a tour-de-force featuring a striking voice and artistry that will dazzle the vision, stun the ear, and demand attention.

Reed’s brand of intertextuality is especially powerful because it doesn’t seek to erase what has come before; rather, he employs a comprehensive archive of political figures, poets, cinema, and visual art as inspirations and burrs to analyze and slant the old gaze. The detailed “Notes” section at the close of the collection, listing the diversity and depth of his influences, offers insight into Reed’s process and both amplifies the poetic impact and encourages readers to think expansively for their own connections.

The questions Reed asks are as ambitious as the ways in which he explores them. Do myths obfuscate reality? How does society demonize what it fears and what might topple its configuration? In “Head of the Gorgon,” which is in conversation with poet Dan Beachy-Quick’s lecture “The Monster in Me Is the Monster in You,” the narrator is:

Strange to them, a gaze fatal and not theirs. Stranger still to be

beheld and collectible and them. What they think I used to be

was, if in possession of eyes as well as agency, preposterous.

[…] here was the stillest

minute slipped between me and the myth of myself[1]

as well as the consequences of such false narratives, here in “When I Am Alien:”

[…] I ungird within an architecture of bone,

unouroborize — a self-sustaining myth driven carnivorous. (54)

One of the pleasures of these poems is how Reed incorporates the work and sensibilities of other artists as support and foil. Yet, even as one sees the threads and influences in his life, the writing, always, is uniquely his. “Head of the Gorgon” is also in conversation with Audre Lorde’s “Coal,” in which the latter wrote:

Some words live in my throat

Breeding like adders. Others know sun

Seeking like gypsies over my tongue

To explode through my lips

Like young sparrows bursting from shell.

Some words

Bedevil me

In Reed’s work the marriage of the poetical and political are inextricably entwined, and his interests are as wide as the world he describes. His dialogue with a well-worn poetic statue — Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass — selects one of the best-known American poems and questions both its premise as well as these states, united and otherwise. There’s a sharp delight in a queer Black poet taking on this symbol of American expansiveness in so stunning a fashion, sharply underscoring all those missing from “I am large, I contain multitudes” and inking our complicity with the atrocities watched numbly from electronica:

I slept in a bed and the children in cages.

I slept in a bed and the children in cages.

The children died in detention.

I paid my bills and therefore

I perpetrated. I paid taxes to be

more effectively terrorized. (36)

In the original Leaves of Grass, Whitman wrote, “I project the history of the future. I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear … Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs.” Reed’s syncopated, sometimes discordant songs — note the repetitions and rhythms below, from the “hides hides” which “lie” “wild” — are his depiction of a different America, our America, one that has yet to fulfill its promise to those it has harmed and continues to harm, those who have risen up, including this poet who has:

been storing the cold in my bones

for you. And the bones? Dressed in black.

My drapery of hairs and hides hides

a pocket where lies folded the vast wild

potential of my killing tool to catch light. (57)

From Freud’s Verschiebung to the movie Alien to classical demigods such as the Minotaur and Achilles, the specificity and thrilling verbiage of these poems reflect Reed’s mastery of language, image, and his diversity of knowledge. Given this and his wide sampling — across music, literature, historical events, and, of course, poetry — readers will feel that many of their brain receptors are stimulated at once (and occasionally as if they’ve placed their finger in an encyclopedic light socket).

But none of these elements are there without a reason; this is intertextuality with a purpose: deft, sharp and unforgettable. In the long-form “When I Was a Poet,” where Reed lightly sources William Cullen Bryant and Robert Frost, with a touch of Alice Notley, the book of Genesis, and John Coltrane, he is conducting a literary chemical experiment that brings forward a new element with a long half-life, far past the ending of this collection. The sum of this poem’s parts significantly exceeds the ingredients because it is Reed performing the alchemy, Reed’s words that are the next verse, offering a new gaze on language and existence:

The poem’s pursuit was apparently to humanize

and the poet’s to petition this universal experience.

I saw the universe. It was black and unbothered.

[…]

I was “a black” “snake. I had” “black sibilance.”

“I was” “built” “like a loco” “motive of” “blackackackackack.”

[…]

I am the hydra of I

and soon I will be the next thing. (74–77)

The Hydra is another representation of how myth can be revolutionized by a turn of the gaze. Rather than an example of a “monster” whose heads are repeatedly slaughtered — this imagery is especially devastating in our current environment — the ability to regenerate is a remarkable resilience in the face of repeated trauma by powerful entities. Throughout this collection, Reed renews both himself and the nature of poetry through these unique — yet unlabored — interdependencies between such a diversity of source material.

As visually and verbally comprehensive as many of these poems are, Reed is an expert in distillation, here encapsulating nearly fifty years of cinema representation in one simple notation: “Guess Who :: Get Out” (14).

In addition to such diversity of content, Reed also manipulates form to great effect. “If We Must Be the Dead” is an “acrostic use of lines” from Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die” and “borrows a phrase from Sterling Brown’s ‘Salutamus’” (91) to form a fourteen-line nonsonnet, which starts with “You misunderstand” and ends:

[…] We are the dead. We set the tone death.

We climb their sleep like bellflower horns, and blow. (81)

The structure of such works — which include the creation of a “device I’ve named CASH (consonantal anagrammatic slant homeoteleuton)” (89) — is admirable, yet it’s the content that shines. There are no gimmicks here, and there are no easy narratives. Each component has a place and contributes complex layers not only to the specific poem but to the overall collection.

In reading these works, there are echoes of the literary grotesque, that which encompasses duality and metamorphosis. Here the artist is not just the creator of the malevolent volume but is also the result of the volume of malevolence directed toward him: “what kind of new / dread animal, / this shape we take?” (13). Reed repeatedly calls out the societal infrastructures whose primary function is to keep the system alive, how “They are looking for proof of the devil. / They have no interest in their kingdom’s architecture” (20).

Sociopathy is often defined as an amoral lack of concern for living things. Then what of a society that can so love Black culture, and pillage it, yet still not revere the creators? How it is so ready “To slowly tear the wings until a thing / torn from itself is its whole self and won’t grieve / a flight it can’t recall” (26)?

In “Every Cell in This Country Looks Like a Choice You Can Walk In and Out Of,” Reed expounds on what this country’s distorted psyche demands, and why:

[…] In the buzz of his country’s decay

I give a form to the chaos. He loves to say

he hates me, meaning his need to use me

confuses him. I want to say I love me

in the language of a place where

it is possible (21)

Though a number of these poems speak to and about those murdered through systemic violence and prejudice — for example, “Open Season” was partially inspired by Georgia artist Shanequa Gay’s exhibition Fair Game and alludes to the murder of Michael Brown, Jr. — these entities aren’t victims, nor are they hopeless. Rather, they speak to a future, their future, even more resonant for the events of 2020:

What they won’t do is enumerate

the ever-fresher types of way I’ve learned

to live beneath the gun. Amid this country’s

latest crazed nostalgias, my body

has been quickest to choreograph a future. (65)

In order to survive, the hunted must be flexible, quick, evolve faster and better than the stagnant society of old flags, old monuments, and old verses. Reed is part of the new guard of writers who continue to make it new, make it relevant, and, most of all, make it true for those who have been kept silent for too long.

Lorde’s “Coal” ends on these lines:

Love is a word another kind of open —

As a diamond comes into a knot of flame

I am black because I come from the earth’s inside

Take my word for jewel in your open light.

Among other earthbound elements, human beings are made of carbon, and the volume of pressure on this poet has resulted in a collection of diamonds: dazzling, light-reflecting, sharp, and impossible to shatter. Reed writes “I have wanted, to the teeth, to own what I love” (27), and he does so here in breathtaking fashion, allowing us the opportunity to do so as well, even as we question our own complicities in the structures around and within us.

1. Justin Phillip Reed, The Malevolent Volume (Coffee House Press, 2020), 44.