'The earth angel, sorting time'

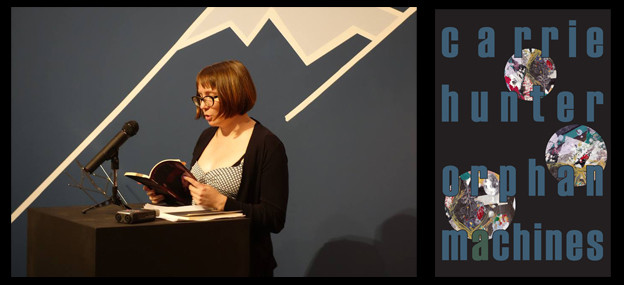

A review of Carrie Hunter's 'Orphan Machines'

Orphan Machines

Orphan Machines

In her second full-length collection, Orphan Machines, Carrie Hunter invites readers to share her preoccupations with philosophy, sexuality, and music. Incited by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari — riffing off their “theory of no leaders”[1] philosophy in Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia — Hunter collages their ideological text, using it as palimpsest and backdrop for her own original poems. As in her first collection, The Incompossible, Hunter effortlessly blends private dialogue with public testimony orchestrated in a variety of forms. Orphan Machines drones a bittersweet urban lyric, and by the end readers may also be asking themselves in public, “Should / I fake normalcy or be real?” (79).

Orphan Machines contains twelve sections of open field and prose poems, reminiscent of the miniature prose blocks in Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons. Like Stein, Hunter shares a fetish for marrying the abstract idea with the material concrete in a rhetorical frankness that I find humorous in its succinctness and quirkiness. From section II, “Between A and a,” the following poem, bearing glints of Stein, exposes the ghostly palimpsest of Deleuze and Guattari’s theory of no leadership, which explores capitalist society as a leaderless rhizome, a “desiring machine” having interconnected and self-replicating growth [2]. Thought, below, is a node branching out, stimulating other nodes of thought:

Theory of no leaders and ice tea

catastrophes. Or latent beads.

Sometimes looking too much at

pictures. Having finally settled on

a plan. Again. Transsexuality’s

anoedipal “resolving.” In each

opportunity is a failing or a

step towards a success that

hasn’t happened yet. Opening is

opening. A memory of the past

is redundant. Until we are Kant

time, illegitimate corresponding,

shall we. (12)

Employing collage and erasure techniques, each poem in Orphan Machines interconnects, blistering in sexuality and music, stirring up questions. What does it mean to have no leaders? Would humans still flock together, intuitively and socially? Is social hierarchy inevitable in all species? How does an anticapitalist thrive in a capitalist society? Traces of theoretical thought move quickly in the above poem — “Opening is / opening. A memory of the past / is redundant” — as poet sorts time. Contained in a prose block, stream of thought enacts Deleuze and Guattari’s social rhizome analogy in horizontal nodes of thought branching out with no pronounced beginning or end. I enjoy this one for the playful slant rhymes in “leaders,” “ice tea,” “catastrophes,” and “latent beads,” while trying to guess what the “plan” that the poet has settled on twice is. And what exactly is “Transsexuality’s / anoedipal ‘resolving?’” Each time I returned to the text, opening the book to a random page, I felt like I was walking onto the poem’s center stage in the middle of Hunter’s mind-bending opera, enveloped in her surreal confessional, “The sound bends and I am in / thoughts of ribbon” (29), smashing up against what she might be seeing or reading at the moment in “Kant / time.”

Sexuality shares pages with philosophy everywhere in the book. In the poem “penetrations, scission, mournful” — published previously in Hunter’s chapbook Inversion Twilight — philosophical residue persists in the peculiar “Earth decoded installs tangential Zarathustra” (25), dragging Nietzsche out onto the stage in a religious time warp and sending readers back to days of ancient Zoroastrianism. The next prescriptive poem that follows, “aleatory resexualization sequences,” ensures readers that “Theoretical nuances cure flux” (26), right alongside the comical “Wanting to destroy the world through sex” (26). “Thorned bisexuality” and the “third sex” (26) make provocative appearances later in the poem, translating into images of sadomasochistic unicorns having orgies inside triangular stables. Hunter’s poetry makes me think that way! Her exploration of sexuality mixes with her penchant for ideology, creating themes that are at times elusive and at other times brazenly clear: “The theme is theming” (29) or she challenges readers to “Guess the theme” (29). Whether it’s theory or a “real dream” (43) from her diary, the poet translates whatever she’s reading into her binarized reality, moving from public to private where found language assists in arranging the poet’s “Serenade, story” (76). Then later in a fickle flip, Hunter bids her readers to “Never mind sexuality” (86) — after dosing us with all kinds of it.

From internal to external landscape, I admire Hunter’s swift synthesis of what’s happening inside with what’s happening outside: “What I can tolerate, placed / in a circle around me” (1). Personal confessions, another one of her preoccupations, testify things like “I / have no thoughts, all of this is outside me” (28), negating the poet’s inner world and relegating her thoughts to external reality. Hunter thinks out loud to herself in her poetry, allowing that which gives her work a reality timestamp of now. From section I, “God is slippery,” guess which line thinks out loud:

This framework dehumanized,

stunned. All the red,

and the click-clack.

The opposite of a swell,

but oceanic also.

What people who wear hats are

trying to express. I forgot the antenna.

The earth angel, sorting time. (3)

Correct, if you guessed: “I forgot the antenna.” The jarring note-to-self ruptures the poem, along with social perception in “What people who wear hats are / trying to express.” Where exactly is the poet situated in her poem, inside a dream or on a bus? In other poems, neighborhood aural interruptions are granted: “That car / is always starting up” (1). Possible overheard conversation is presented in quotations, “‘I gave you respect, now you give me / mine’” (83). And wherever the poet asserts

herself — “I follow destruction everywhere” (2) — she does so with a bang and an inner voice that often ironically questions itself. In one skillful line break, linking the first two stanzas that pulsate with lacunae in “Cinematronic/Syntagmatic,” Hunter mediates internal thought with external declaration of her depression, interiorizing from a “thunderous mind,” to outing that collectively “we are trees in bloom”:

So depressed, I can’t

keep my head up. Thank God there are

walls, thunderous mind

peanut droppings. The homeless couple walking the perfectly

coiffed standard poodle. Transference’s guise, or sorcerer, or

sexuality. Obvious drone of physicality. Lakeside, shore times

we are trees in bloom. (84)

Witness to the urban desolation surrounding her, caught in the snapshot of the homeless couple, depression is another subject-node that surfaces within the collection. Planted within her poetry, Hunter becomes subject herself, evidencing “Deterritorialized” (29) social “topographies” (5), an “orphan” (94) in the “labyrinth” (94) of society’s desire machine in her “San Francisco hoodie” over her “Oaklandish wife-beater” (68). Yes, “Thank God there are / walls,” but also “Thank God” for Hunter’s sense of humor which offers release in moments of internal stress. A line such as “In the middle of yoga, / thinking of slicing my wrists” (25) is tragic. Can yoga render suicidal thoughts? Isn’t it supposed to restore, and when done communally, everyone becomes one collective higher thought? But slicing wrists enters the mind, bringing the poet to an utterly vulnerable place in public space, while feeling that “Everybody’s nuts” (26). Hunter’s dances between her externalized landscape of social dissolution, “Our roots are burning buildings down” (84), and her internalized landscape, a “Naked process, a divided / intensity” (25), afford her the irony of “An open privacy” (25). Confronting the “shadow” (86) of her broken body-machine, “pierced and falling” (85), she enthuses, “Hopefully my depression will / continue” (77). Who finds depression hopeful and why do I laugh? In a positive light, depression makes a case for affording Hunter some therapeutic writing, driving the poems with a touch of tragicomedy. What appear to be inside jokes pop up in surprising places: “I forgot to do the one / thing but remembered the chocolate” (84). I couldn’t help but snicker. Or maybe there is absolutely no humor in Hunter’s poetry and the joke is on me.

While reading Orphan Machines, readers will become aware of how music shapes its engines, a liberating source from which the poet can write. There are clear moments in the collection when I feel that the poet-conductor reaches her higher octave in a refined lyric, releasing herself to sound because “The music fights / poetry” (50). In section V, “De-Axiomatization,” Hunter, cyborgian in her “Elegant spacesuit” (29), aspires to a sonnet tempo:

Sometimes

you catch up

with your thoughts

and you find yourself

left

with music. Because

you said the code,

forgot the sun,

made an error in judgment.

If the stars are coming out,

this is the sound they make.

Covering the damage

I only thought of doing.

What seems close

is a virus (36).

Hunter’s passion for language is clear, but her love for music reigns, laboring now and then in alliterative sound play: “Plith plinth Pliny / Plentiful” (43). I’m excited by the surreal tones of all the poems in Orphan Machines, which were “written to drone/ambient music,” as Black Radish Books shares in its press release. In the above poem, I favor the poet’s admission that “I only thought of doing,” revealing another subtle layer of the poet’s afterthought or inner conscience which we rarely see in poetry. This poem also second guesses itself with an uncertainty that mirrors John Keats’s theory of negative capability. Then later in the collection there are moments when confidence is restored: “I can read music. I can count / time” (92). Readers will enjoy the music Hunter makes and can count the many musical references that appear, joining her in the question, “What would I / do in an ensemble?” (92). Elsewhere, diction choice intuits its way through sound. It’s not just that it sounds good: we open up to possibility, “Reverberation / leads [us] into mystery” (60), and varied diction allows for numerous meanings in each of Hunter’s lines. Toward the end of the collection, the poet-skeptic hesitates and questions: “Or do I need music at all?” (79). In the final section, “The Fourth Socius,” music merges, “The / bells are getting lost in this maze of / drums” (96), with thoughts now diminishing.

Closing the book and staring back into its cover art by Michael Floyd, which depicts three planetary orbs filled with a mix of collaged images, including trees and their visible root systems, I think of how fragmented and schizoid the societies that we construct — physically and ideologically — are. Like Hunter, we too are earth angels communicating through various recycled thought-nodes from one main social rhizome, “we are molting, we are a social / act we are identity-less” (83). Living in a time where capitalism comes under scope and its ideology is questioned as a systematic way of life, Orphan Machines is timely and spot-on in its wondering whether or not we should be “real” or “fake” in an artificial and duplicitous capitalist society. Staring into our many screens, what does “normalcy” mean anymore with our daily, sometimes obsessive, indulgence in social media? Is the internet today’s “real” social rhizome? And what is having an “open privacy” (25)? Posting private things publicly online? Hunter speculates for us, “Or is it the private / that has to be abandoned[?]” (93), admitting she is “Trying to create a suspenseful / pause but just inventing a rift” (77). A poet who can’t “fake” it no matter how many attempts she makes, in the end she comes out “Real real real” (83), charming her readers with poetry riddled in self-conscious irony, conundrums, and potentiality. Inflaming thought, the term urboscape came to mind while reading Orphan Machines, and I’m not even sure if that’s an official word yet. Pure magic, Hunter’s urban lyric gives you the power to construct new concepts; her original score will expand your mind with its ensemble of “slide” guitars (86) and “Thinking chimes” (28).

1. Carrie Hunter, Orphan Machines (San Francisco: Black Radish Books, 2015), 12.

2. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1983), 10.