Cooking a book with low-level durational energy

How to read Tan Lin's 'Seven Controlled Vocabularies'

Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004 The Joy of Cooking

Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004 The Joy of Cooking

Tan Lin’s Seven Controlled Vocabularies (7CV) is not about what many people seem to think it’s about. I’ve seen reviews that take the story of meeting his wife at a Macy’s event as if it were straight autobiography; I’ve seen its reproduction of Laura (Riding) Jackson’s Foreword to Rational Meaning taken as an affinity between his book and her theory; I’ve heard people compare it to Adorno or say that it is a manifesto. These misreadings are interesting to pursue, as they signify exactly what the style of the book does — tempts us to lapse into certain habits of reading (focusing on what is most recognizable to us, projecting our own desires and interests into places they aren’t, etc.) instead of actually reading the book for what it is, does, asks of us. This marks one of Lin’s long-standing goals: to create texts that get the reader thinking about reading environments, or how various texts trigger certain kinds of reading.

Yes, 7CV teases at being both a book of aesthetic theory and straightforward stylized autobiography. It is certainly concerned with the meanings of words. And while it concerns topics such as beauty, art and society, and meaning creation, and contains elements of both theory and story, very little of the content is what it seems at first reading. The book does not approach its issues directly, with hammer and tongs, as it were. Wherever you think you’re reading in one framework, you’re often actually reading in several others.

This book is unlike most of its contemporaries. It doesn’t take chunks of sampled text and leave them for the reader to work with, and it doesn’t severely cut up and-or juxtapose. Where a typical post-Langpo book tends to maintain categories as they are commonly understood and either place them in relief or shred them so that meaning is compromised for the purposes of social critique, Lin’s work cooks categories down to a base, opening and expanding them into each other like ingredients you’ve never had prepared so well before. With an almost scientific precision, Lin’s style cross-pollinates the standard vocabulary systems for organizing information, and in doing so opens up new horizons for thinking through the reading environments for those vocabularies. The result is a new style of thinking and writing that produces in the reader a less clear sense of where one category begins and another ends. It’s not merely about the relationships between things and ideas, but about how we read, and are always reading, often according to methods and guidelines we are not entirely conscious of.

Lin has published four books to date, including 7CV. His more recent books have emerged out of sourced or ‘marginally authorial’ writing processes such as collages of material plagiarized from the internet (Heath Plagiarism/Outsource, Zasterle Press, 2009), and riffs on ambient and electronic music (Blipsoak01, Atelos, 2003). Like Heath and Blipsoak01, the work of 7CV is sampled and written-through, collaborative and democratic, but not does not register as polyvocal. Its style, on the level of sentence and paragraph, is glassy and seamless, insinuating the warmth of statement. It pulls its sources together with results that resemble more airport muzak than hip-hop, less post-Langpo and more something we haven’t seen before. Any interruption or seam-rending happens more at the level of the book—between chapters and pages, between the cover displaying the front matter data and the back of the book looking like a front.

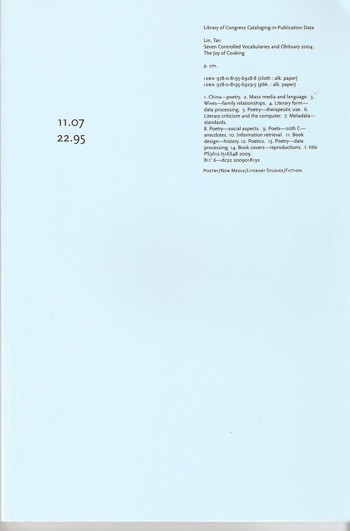

In discussions of his turn toward this kind of work, Lin often talks about wanting to make reading easier, more relaxing, by creating a smoother textual surface than what his readership had become accustomed to with Language Poetry. 7CV, the latest, works many of the same ideas about writing, but the surface of this text is the smoothest yet. While this smoothness often induces reading strategies appropriate to popular forms such as the novel, autobiography, or restaurant review, the descriptors locating the book within American library databases inform us it is to be categorized in ways that don’t seem as apparent on first glance: poetry, engagements with mass media, cookbooks, book design, and the product standards of the publishing industry—among other topics. Lin seems to want us to attend to this right away, foregrounding these headings by moving them to the cover of the book, away from their usual place in the unreaderly front matter. They are clues for how to read the book. They activate its poetics. A reading framed by these descriptors reveals a text less concerned with the truth value of any statements seemingly made, and more concerned with blurring the lines between the categories and genres it plays with.

Because of this emphasis on blurring categories, most of the text of 7CV cannot be taken at face value. This makes it difficult to quote well. One cannot say “Lin asserts” or “Lin thinks” and then take a sentence or phrase from the text. Much of it is just exemplary phrasing for whatever vocabularies are under consideration. He does not necessarily think what it says. If studied too closely at the sentence or paragraph level the text often frustrates as much as it holds sense seductively just within reach.

Lin has come to be known for what he calls “ambient stylistics,” a style he has described in a few interviews, but whose greatest articulation yet may be 7CV. In a 2005 “Close Listening” interview with Charles Bernstein, discussing ambient stylistics in his Flash Video/poem-films, Lin provides us with a key insight into the concept of ambient writing when he talks about his interest in Stein’s idea that a reader cannot help but create meaning when any combination of words are put together [1]. He asks, “Can three words that appear together be made into a narrative?” Lin tested this idea in his poem-film experiments, which bring words together in various combinations of three on the screen. In the animations, there are always three words and no other images. The program sequence allots each word the same amount of time on screen, and all words fade out at the end simultaneously. The question is how far apart in meaning can the three words be and still produce a narrative?

We watched one of these with students when Lin came to read and talk where I teach at CUNY-LaGuardia Community College in May 2009. He asked students to talk about how they processed the language during viewing. Beforehand, he told students he intended the video to be soothing, yogic, and invited students to view the film meditatively. After watching for a few minutes, he asked them to discuss connections they made between the words. Students volunteered associations they had made, and what we discovered was that they tended to either be narratives or flashes of scenes involving the meaning of each word. One student saw the same woman doing various things associated with the words on the screen.

7CV builds on this experiment, moving it from film to the realm of the book (though it is useful to think of the book as working like a film, employing the dissolve as a way of moving across discourses), and from combinations of discrete words to explorations of controlled vocabularies, many from the publishing industry: poetry, fiction, autobiography, theory, art book, and so on. How many generic terms and reproductions of images are required to trigger a reading response of “art book”? How many references to positions in the structure of the family (wife, father) before the assumption “autobiography” begins to creep into the reading? In this sense, Lin’s work is genuinely experimental, recalling not only Gertrude Stein but the early-twentieth-century psychophysical studies of Hermann Ebbinghaus. Ebbinghaus, whose experiments were designed to test memory through the memorization and recitation of randomly-chosen syllables, noted that, at least initially, his subjects tended to produce meaning involuntarily, forming narrative chains through the association of the test syllables with known words. (It is worth noting that Stein took part in comparable ‘dissociative’ language experiments during her student years at Harvard University.)

7CV builds on this experiment, moving it from film to the realm of the book (though it is useful to think of the book as working like a film, employing the dissolve as a way of moving across discourses), and from combinations of discrete words to explorations of controlled vocabularies, many from the publishing industry: poetry, fiction, autobiography, theory, art book, and so on. How many generic terms and reproductions of images are required to trigger a reading response of “art book”? How many references to positions in the structure of the family (wife, father) before the assumption “autobiography” begins to creep into the reading? In this sense, Lin’s work is genuinely experimental, recalling not only Gertrude Stein but the early-twentieth-century psychophysical studies of Hermann Ebbinghaus. Ebbinghaus, whose experiments were designed to test memory through the memorization and recitation of randomly-chosen syllables, noted that, at least initially, his subjects tended to produce meaning involuntarily, forming narrative chains through the association of the test syllables with known words. (It is worth noting that Stein took part in comparable ‘dissociative’ language experiments during her student years at Harvard University.)

Lin says in his BOMB Magazine interview with Katherine Sanders, “Style is what is statistically likely to induce a reading” [2]. In other words, a statistically significant showing of lexical elements and other features associated with a specific controlled vocabulary, say poetry, tends to produce, involuntarily, particular forms of reading. One reads differently when there are line breaks. One reads a certain way when it seems the text is guiding the reader through a recipe. Anyone might lapse into certain reading habits by way of textual cues or even the marketing strategies used to sell the book. With this realization in place, Lin’s book playfully cues, samples from, and surfs around specific structures and vocabularies, mixing and echoing and reversing throughout. The vocabularies of painting, architecture, autobiography, design, shopping, etc, slowly shift and blend.

When asked about the connection of 7CV to ambient stylistics (Lin had published an earlier edition on Lulu.com), Lin described the book as “a piece of low-level durational energy” emphasizing a long time concern of his to create reading environments, but in this one “distinctions between recipe, novel, etc are dissolved” (“Close Listening”). He compares this to visual artists like Jorge Pardo who renovated a house, presented it as art, and had an “opening” there, blurring the line between art, carpentry, and gallery. Works like Pardo’s made Lin wonder about the possibilities for a generic poetic work for today. He realized “it would be metadata/controlled vocabularies.” Using these generic terms, he says, he wanted to create a reading environment where “a novel … could be confused with or blurred with airport or architecture.”

This blurring of categories across the book creates a peculiar sensation of drift, float—a haziness—while reading as the surface of the text shifts laterally across the reader’s expectations; which makes it quite a different reading experience/environment than any other I know of. So the reference to Laura (Riding) Jackson (about two-thirds of the way through 7CV there is a scan the 1986 Preface to Rational Meaning) should not be taken to mean Lin has affinity with her theory of radical meaning. 7CV performs mostly in opposition to Riding’s theory (this is perhaps the one binary remaining in the book). Where radical meaning posits that a word has rigid intrinsic meaning that must be preserved, Lin’s ambient stylistics moves against that toward the edges of meanings. In 7CV there is no rigidity of aesthetic terminology, no ultimate truth to our vocabulary. Lin wants to soften meaning, as opposed to Riding’s hardening meaning; he chooses drift where Riding chose focus.

The vocabularies Lin works with, pulled together by a bland elliptical style that seems to hold them in solution, will often suggest a certain genre to the reader, setting up certain expectations for what will be covered, but the text humorously subverts those expectations as often as it sets them up. The play with vocabulary creates a reading game for the audience to think around the limits of both genre and the construction of books, treating those constructs as material bases to draw from. The game consists of playing on a series of vocabulary markers as they are encoded in readers, and the book is more concerned with playing on those codes than saying anything directly from within them. More, the suggestive nature of the content not only plays on our habits of reading but consistently tempts us to lapse into those habits.

The best example of this may be the section that offers a first person account of meeting one’s wife at a flash mob event at Macy’s. The story told reads as autobiographical, and even contains the name of Lin’s wife Clare Churchouse. But this narrative is called into question as the wife enters the story and reports that this is not where they met, and offers her own journal as evidence that they met two-and-a half years earlier. With such a time difference, one already has to question the degree to which the reading “autobiography” can be applied. It may be that Lin has that bad of a bad memory, but the question this text opens up inspired me, with Heath in mind, to look for source material online. In fact, the date and description Lin gives for the flash mob event match the description of the first flash mob ever in the Wikipedia entry for “Flash Mob,” strongly suggesting that he borrowed the flash mob description and mixed it with that which triggers the reading "autobiographical" in order to place those categories in relief. (Of course, it is also possible that Lin edited the Wikipedia entry to match his book, but we'll leave that for another essay.)

The romantic personal story available in this section of 7CV is easy to believe if you don’t want to see the evidence that it is likely (at least in part) a falsification. The reader is invited to “read” autobiography, to lapse into that comfortable pleasure, but is also given the opportunity to begin thinking about the triggers that evoke “autobiography” and why even the most trained readers are so susceptible to its codes. It is also worth noting that the flash mob in question involved a critique of shopping. Combining these issues in this segment also creates space for readers to consider the relationship between the forces that produce shopping, the autobiography, and the subject that desires autobiography.

Every chapter is an example of this kind of category blurring. In the chapter titled “Field Guide to American Landscape Painting,” a reader might find himself expecting everything to be about American landscape painting, but the text concerns topics that seem marginal to that discourse. It concerns various forms of sequencing, primarily as found in other media outside painting: A-Side vs. B-Side, top vs. bottom, how many things the human brain can remember at once, the convention of numbering plates to display paintings in a book about painting, that a poem could instigate looking more than reading, that a novel is most often ordered according to what will make it most hypnotic and mesmerizing—all of which seems to come down to how “everyone says ‘cogito’” (22). The revelation to be had from reading between the categories of “field guide” “landscape” “painting” “sequence” “narrative” “cogito” etc. is that each category already contains elements of the other. On the one hand, the controlled vocabulary system for landscape painting is the mediatory apparatus that allows one to speak about painting and also for painting to exist as a function of particular discursive practices. On the other hand, that vocabulary system, at its margins, can be used to re-orient the way we think of other media, and vice-versa. This opens up an opportunity to think about how we define thinking itself: the way we have been trained by discourses on narrative to think of novels or even our own personal stories, or the way we have been influenced by landscape painting and books about landscape painting to think of certain landscapes as beautiful. What is the difference between and frame and a fence? How do those discourses influence what we think thinking or art or nature is?

Reading this way, one can see that the chapter title already suggests a network of relations between words whose opposition and reconciliation lead one towards this central concern of the book—dissolving controlled vocabularies. A painting is a two-dimensional representation; a field guide suggests preparing for experience in a three-dimensional landscape where one might want to identify wildlife or rocks or minerals. One has field guides for birding, recognizing flora and fauna, but not painting. Moreover, field guides help users distinguish animals and plants that may be similar in appearance, but unlike a field guide, this section (and all of 7CV) forces a reader to think about similarities between categories, to think at their fuzzy boundaries. 7CV is more of an unfieldguide, or a unified field guide. Can we look at paintings the way we look at wildlife? Study them as emerging forms in environments? What is the environment for painting and how has it determined what survives?

Surprisingly, there are no photographic reproductions of paintings in this chapter, but instead, several pages with only the language typically used to catalog paintings when they appear in a book: “plate 1,” “plate 2,” and so on, bringing a reader’s attention more to the production of a book about painting than onto painting itself. In that spirit, reading this chapter one might ask: How much text does it take to instigate the reproduction of an image, and how much reproduction of an image instigates a book? And, crazier yet, in the context of a book partially titled The Joy of Cooking, the word “plate” begins to accrue meaning that would otherwise be considered quite marginal to any consideration of painting. But then again, any viewer of Top Chef knows that presentation matters; two seasons ago the winner was called the “Picasso of Presentation.” This line of connection gets reinforced later in a section describing painter Bruce Pearson, at home, attempting to reproduce a recipe from a high-end New York restaurant.

The third chapter, titled “American Architecture Meta Data Containers,” also does not go directly at architecture in the traditional sense, but explores the paratext of books (back covers, barcodes, etc.) and their construction, blurred with more marginal reading contexts such as designer clothes, product tags, and credit card bills. Here the vocabulary for “architecture” and related concerns of space, territory, etc., dissolve into considerations of reading: American Written English (AWE) is “a series of spaces”; the page is “a quadrant filled with various codes that resemble flags”; “literature should function as a pattern with a label on it”; a Louis Vuitton bag has scrambled letters all over its surface “in order to be read”; cineplexes function like pastoral poetry. And here we find the following sentence repeated twice: “Literature as Space with Language Attached to It,” bringing the question again to what this all means for how we define/categorize literature. What would we learn if we defined literature by its spatial relations first, treating language as an accessory? Most of us are not trained to attend to books or text in this way, and yet Lin’s work here suggests that so much that is happening, including the shape things take both within the space of the book and outside of it, unconsciously affects how we read.

In this chapter, the vocabulary of architecture helps to frame a consideration of reading as a spatial experience: “… reading is generic and immaterial like most of the buildings we pass through [ ] and the streets we happen to be on. [As anyone] [who has spent time on the Las Vegas strip] can tell you.” The use of brackets in the second sentence suggests we take seriously the contents of the brackets in the first, that the brackets are both meaningful and have essential information inside them. So the empty space in sentence one is pregnant. It seems to invite us to compare buildings and brackets, and what comes to mind immediately is things treated as parenthetical, aside from the matter. This suggests that we pass through buildings like we read [and don’t read] brackets and bracketed information.

In a context where we are already asked to be thinking of that which triggers us to lapse into habits of reading, we might think of a parenthesis as a representation of the unconscious, a kind of space of repression. We know we are unconscious of a great deal of what is affecting us when we read. Why not also the spaces in which we read. The physical places where reading takes place—parks, libraries, cafés—are generally considered “outside” the book, but influence it nonetheless. Buildings may be thought of as the brackets in which we read. Reading happens within, between, and alongside a variety of structures, but how many are we aware of during any given act of reading? Likewise, a book and its readership are in part created by the generic and meta data structures ostensibly “outside” of it. Furthermore, feelings and expectations often seek fulfillment “inside” a book, as when I buy a book marketed as an autobiography of Bréton, hoping for straightforward gossipy life-story beach reading, only to find out that it too is constructed according to surrealist principles and will not deliver the reading experience I wanted.

The section “2 Identical Novels” plays out these concerns further. Where, with such a title, one might expect a story or comparison of stories or the way they appear, one instead finds oneself immersed in a discussion of cooking and recipes as “typologies for those emotions we forgot were inside of us.” So questions might arise: How are novels (and their similarity (identicalness?) to each other) also typologies for forgotten emotions? How are novels like recipes or cooking? Where a novel is designed to induce particular feelings or habits of reading, or draw on ones that seek empathy, the recipe produces a flavor profile persons with certain experience can recognize. Where a novel has a fundamental reproducible form, a recipe is also endlessly reproducible.

This chapter gives way to a brief discourse on potentiality: “An emotion, like a recipe, is always waiting to become the thing that it already is. […] People who think they have their own emotions are incapable of empathy or cooking.” Feelings, like genres, can be difficult to identify, but we learn to identify them and are often uncomfortable when we can’t. Many people enjoy or even need a certain amount of coherence in the handling of literary genre as well as in the use of spices. Experimenting with either can produce a number of effects, from “this has X influence” to “those two flavors/approaches do not work together.” So maybe the question in 7CV is whether “the novel” has about as many options as there are flavor principles, ways material can be combined to create recognizable effects and connections, pleasure or displeasure, identification or dysidentification in the reader/eater. Overwhelmingly the novel—especially the popular novel—like a recipe, formulaically induces target results in the form of certain emotional responses. Those responses also tell us a lot about how “Everyone says cogito.” What is the relationship between what we are willing to read and what is marketed as a novel? What is the relationship between what we are willing to eat and what we have always eaten? What lurks at the far edges of anyone’s answer is the avant-garde, or perhaps just distasteful.

Categories aren’t blurred only within the chapters of 7CV. As much blurring takes place across them. Where in the field guide/landscape painting chapter we consider how a poem might be sequenced to instigate looking instead of traditional poem-reading, in the architecture/metadata chapter we find further consideration of reading and appearance. Among the more thought-provoking sentences for me with regard to this are “the most powerful texts function like logos, a code wherein words and reading are synthesized into looking and staring” and “a logo-like text is text and reading instructions as one.” Should this be read to mean Lin wants texts that are logo-like? I wouldn’t force the text to choose, but instead consider what can be learned from thinking about reading as it happens in the case of logos.

On the one hand, the Louis Vuitton logo works because it is a bit indecipherable and requires a certain amount of reading for anyone to get it. You have to stare, invest, figure it out. Then a moment of recognition occurs—and as of that moment the logo has claimed a small bit of real estate in your brain (that’s branding). On the one hand, this is the kind of thing Naomi Klein has revealed for the manipulative invasion of space it is. But on the other hand, the logo induces reading while teaching us something about how we read, perhaps the way Pollack once helped us see painting differently. This fact might also teach us something about the way we read other texts, like poems.

When one looks at a long, thin piece of line-break-driven writing, one “knows” it is a poem before one reads the words. The line-break writing announces itself as “poem” from afar like a giant Chanel logo on a t-shirt worn by a stranger on the subway. Then when one does finally read the language, certain assumptions about what a poem is/does will influence how it is received. If what happens there doesn’t meet expectations, a reader might question whether such a piece meets the standards for the genre. They might in effect claim false advertising. Readers often will not recognize a poem as such because they are bringing traditional, and often very rigid, practices to the act of reading. Many people dismiss Language Poetry because the language is too shredded. Many people look at books like Lin’s Heath and see huge chunks of plagiarized, prose-y text and say “that’s not poetry” and “that’s not writing.” But many other people look at such texts and learn something about both the genre and the act of reading. Any time something unfamiliar begins happening within a genre, readers may want to push the material out and say the descriptor “poetry” cannot contain it, but the reality is often that these challengers to the genre are redefining it, re-branding it, and teaching us as they do.

7CV occupies the limit space between generic terms; how is a blouse like a poem? How is a strip mall like a film? Observing these forms in terms of how each instigates reading, the central question becomes what instigates a reading, what codes do people respond to in the same way across a wide variety of objects? Furthermore, how are the various forms of non-reading also the products of systems of reading? Is there anything that is not instigating reading? He creates blur around these categories not for the sake of playing with signifiers, but because the process of softening these categories, feeling their edges and experiencing content as a statistical aggregate, ultimately opens out onto a much larger question of cultural production and the role of metadata in it. Metadata and controlled vocabularies play a large role in how we read. Not only is any object of art or literature defined by the multitudinous descriptors and frameworks that cue our responses to them; these works are artifacts of production or moments in a work-flow that does not stop with the consumer, but carries thru in the production of scripted responses. In this sense the content of designer clothes, like the content of the book, is identical with its frameworks.

Metadata emerges as one of the central concerns of 7CV not only through the play at dissolving controlled vocabularies, but through consistent reference to the manufacture of goods and services and tracking of sales. Images of or reference to bar codes, backs of books, clothing tags, credit card bills, shopping, restaurant matchboxes and the like appear throughout. The text becomes less about the genres themselves and more about how texts and objects are positioned within flows and systems. This emphasis, in the context of thinking about reading, ultimately figures “literature” in terms of work-flows and mechanisms of exchange. But just as this book cannot be separated from its marketing and American library database categorization, it also cannot be separated from the work at the compositional phase of production.

Both the exposed raw info of the cover image and full title Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004 The Joy of Cooking, play with descriptors in unusual ways that often point to things ostensibly “outside” the book. For example, when I first read the subject heading “poetry—therapeutic use” I assumed it was ironic. My own somewhat anti-confessionalist training surely influenced this reaction. But in the context of thinking through the book in terms of work-flows and the [false] inside/outside division of the book, it occurred to me that my own bracketing off of “poetry as therapeutic” may be yet another of the categorical limitations this books challenges. Who’s to say the author wasn’t experiencing personal difficulty during the production of this book? Who’s to say struggles with attention and memory are not behind the new form of writing we find here? Perhaps book-construction-work and personal difficulty re-frame each other throughout, and to therapeutic effect. Or in a whole other sense, perhaps every blurring of vocabulary marks an important event in the life lived ostensibly “outside” the book. Perhaps 7CV is autobiographical in ways that are submerged but everywhere, and lived events are generic driving forces in the composition phase of the book.

The parts that read most immediately as autobiographical, like the story of meeting his wife, are clearly partially plagiarized, but perhaps some of the parts that do not register as autobiographical also contain personal elements. In his interview with Bernstein he talks about the Joy of Cooking being the book his Chinese family learned American cooking from. There isn’t much direct address of that story in 7CV, but the title memorializes that fact, and cooking, cookbooks, and restaurant reviews are referenced throughout, calling us back to that part of the title. Thinking autobiographically, I also began to wonder if the backs of books displayed in the metadata chapter are books that somehow influenced 7CV. It might make sense to think of, for instance, Gary Sullivan’s How to Proceed in the Arts as influencing 7CV. And while some of the autobiographical elements may be Lin’s own, who’s to say someone else’s story, found on the internet, isn’t a story shared by many? Saying otherwise might make us incapable of empathy or cooking, remember? In the end, Lin has produced a text that on the one hand appears fairly seamless in its writing, but on the other hand is radically dispersed and empathetic, while also suggesting that there are an abundance of stories and processes rendered invisible in any book.

Upon first reading, autobiography seemed to be part of the project, but knowing Lin’s work I was hesitant to take that at face value. But after many rereadings, autobiography has re-emerged for me as central to this project. Like Breton’s Nadja, 7CV views autobiography not so much as a straight story of a life, but as a catalog of important moments, somewhat disjunct from each other, but ultimately recognizable as containing the pivotal problems and questions in one person’s coming to be who they are as an artist. But where for Bréton the stories create a picture of his most important surrealist influences and experiences, Lin’s autobiography is a series of ambient constructions built around the vocabularies and codes that have influenced his life/practice, with each of these constructions organized to alternately trigger or diffuse the reading “autobiography.” This raises the question: where does the construction of the book begin and the life lived outside it end? In the BOMB interview he describes his relationship to this question, suggesting the distinction itself is false: “Context is more important than content. There is a lot of personal and extra-personal communal history (errors of attribution: death, tragedy, etc.) beyond a book’s covers…. Every book is an abbreviation/revision that erects some sort of false distinction or difference between reading and non-reading, between the life lived inside and the life outside the book. I wanted to exteriorize the ecosystem of reading as much as possible.”

In the end, I have come to understand 7CV as an ambient autobiography of a book about ambient autobiography. Lin created a book out of his life, which is largely made up of what he reads, how he reads, and his relationships to food, friends, and art, and the ways all these things inform each other.

photo of Tan Lin by Lawrence Schwartzwald

1. Tan Lin and Charles Bernstein, “Tan Lin in Conversation with Charles Bernstein,” Close Listening, May 23, 2005, Clocktower Studio, New York, NY, http://mediamogul.seas.upenn.edu/pennsound/authors/Lin/Close-Lstening/Li....

2. Tan Lin, interview by Katherine Elaine Sanders, bombsite.com, March, 2010, http://bombsite.com/issues/999/articles/3467.