On 'Both Sides and the Center'

A review of the festival, part one

![Bhanu Kapil’s performance “Schizophrene [Remix].” Photo by Harold Abramowitz. Bhanu Kapil’s performance “Schizophrene [Remix].” Photo by Harold Abramowitz.](https://jacket2.org/sites/jacket2.org/files/imagecache/wide_main_column/Screen Shot 2011-09-10 at 3.34.57 PM.png)

Both Sides and the Center

Both Sides and The Center

If the centre has the place then there is distribution.

That is natural. There is a contradiction and naturally

returning there comes to be both sides and the centre.

That can be seen from the description.

— Gertrude Stein, “Rooms,” Tender Buttons, 1914

Both Sides and the Center, a three-day experimental literary festival, took place recently in Los Angeles. Superbly curated by Amina Cain and Teresa Carmody, and in association with Les Figues Press, the first two days were hosted at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House, with the third day at another Schindler-designed home, the Fitzpatrick-Leland house.

Amina Cain and Teresa Carmody welcome everyone at the Friday night reading. Photo by Harold Abramowitz.

Writers were invited to engage with the structure and spirit of the 1922 Schindler house, renowned for its innovative, modern design and vision. Schindler constructed the house as a live-work space to be shared by two couples (originally, the Schindlers and the Chaces) with a joint kitchen and common area, and individual studios. Integral to Schindler’s floor plan is an inventive merging of interior and exterior space that consequently revisions divisions of private and public space. Sleep quarters are rooftop, tree-shaded bed baskets. Outdoor courtyards with fireplaces are designated living rooms. Glass panels meet concrete floors and walls to invite outside light and looks in.

Cain and Carmody encouraged featured writers to create works inspired by Schindler’s architecture whose boundaries play at inversion to emphasize permeability over separation. The dynamic responses the curators elicited reflected on both the physical site and the multiple themes generating from such considerations, for the Schindler house is not only home but also container for intimacy, familiarity, strangeness, and exposures of all sorts.

The first night’s opening reception was a literary reading with writers Michael du Plessis, Jen Hofer and Myriam Moscona, Bhanu Kapil, Amarnath Ravva, Sophie Robinson, Anna Joy Springer, and Vanessa Place. All read work thematically connected to the event and to their Saturday pieces.

Writers and guests returned to the Schindler house on Saturday for an evening of installations and performances. With the exception of Robinson’s photographs and needlepoints, which hung or lay around the house, each writer occupied a particular — entryway, studio, nursery, restroom — that produced a series of encounters for the viewer entering the space.

Two of Robinson’s black and white photographs hung opposite the front entrance. Each an image of a lunette arched above a doorway. Using text selected from her poems, the words “do not leave” mark one arch, with “go away for a long time” on the other. Along with Robinson’s other strategically placed pieces, these photos remind one of the often contradictory imperatives always acting on a body entering a place.

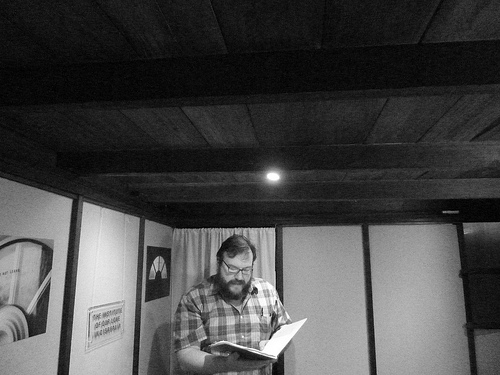

Also positioned within the circumscribed area of the entryway, John Beer’s “Peripatetics” performed a textual wandering of interval readings and recordings. People were invited to listen and then participate by written response to a choice of Beer’s prompts. Drawing from the works of Beckett and Joyce, Beer’s piece effectively evoked the house’s modernist history.

John Beer reading in the entryway with Sophie Robinson’s work on the wall beside him. Photo by Harold Abramowitz.

Recalling modernism and then some, Michael du Plessis’s “The Twitch of the Tablescape (A Comedy of Manners)” faced into the corner Chace studio. While du Plessis’s title suggests satire, his performance was also homage. Du Plessis sat, alternatively bound, blindfolded and ballgagged, or affably reading a viewer-selected “Endnote” from his equally (and rightfully so) erudite and risqué document of sources. His table of curiosities — national monument pillboxes, skull paperweight, snow globe, The Golden Bough — were arranged in asymmetrical concert with his endnotes, which ranged from Foucault on Roussel to The Story of O. His literary and corporeal inquiry provocatively reopened questions of modernist aesthetics through textual entanglements of Southern California architecture, the semantics of sado-masochism, Barnes, Brinig, and Klossowki.

Michael du Plessis at his tablescape. Photo by Harold Abramowitz.

Amarnath Ravva’s video installation “This Movement Is Our Own” explored the more personal history of the Schindler house toward a meditation on nature and home. Retelling the story of Schindler’s visit to Yosemite, which became the retrospective inspiration for his visionary architectural plan, Ravva looped lovely time-lapse photography stills of Anza Borrego’s night sky with an accompanying, looped reading. Displayed in a boxed screen on the floor, the sublime is sublimated into the body looking down on it, asking one to reconsider, as Schindler did, previous conceptions of body and place boundaries.

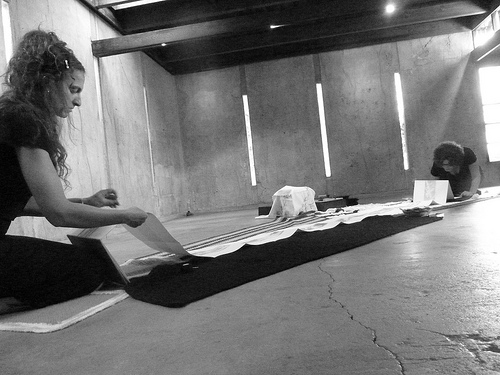

Jen Hofer and Myriam Moscona’s “la casa por la vantana/past the open window,” framed as a private scene of artistic communion, invited passersby in to view the choreographed performance. The room arrangement included an old record player, pile of 78s, and knitted blankets open on the floor, with Hofer and Moscona kneeling opposite and at a small distance, working together, sewing and writing toward one another, in a book folding into itself.

Jen Hofer and Myriam Moscona’s “la casa por la ventana/past the open window.” Photo by Harold Abramowitz.

Anna Joy Springer shifted connotations of private and public space with her “Inside Voice Oracle” performance. An announcement posted on the rear restroom door gave directions for the “personalized oracular narrative for an audience of one” to take place inside. One entered the restroom, rang the bell attached to the plunger earphone hung from the ceiling, and waited. Located outside on the roof above the restroom, Springer assigned and sang to the listener a bird of fortune and its attendant forecast. Hers was an intimate encounter that showed the different shapes that proximate relations can take and the sounds alternative epistemologies can make.

Vanessa Place and Kim Rosenfield’s “SCUM 1976 (2011)” restaged Carole Roussopoulos’s “S.C.U.M.” by way of Lacan’s maxim la femme n’exist pas, and in accord with Place’s larger Boycott project, which changes all pronouns in selected canonical feminist texts from she to he. The video installation, appropriately in the Pauline Schindler studio, included a monitor of Place and Rosenfield just out of the frame, across a table from one another, Rosenfield typing and smoking as Place reads from “SCUM.” With Andy Warhol supplanting Valerie Solanas on the book’s cover, this “SCUM” is Place’s with the pronouns leveled into sameness. At the same time the video updates Roussopoulos’s piece with the use of a laptop for a typewriter and Place’s appropriated and altered text, this video is set on a desk with two empty chairs, microphone, typewriter, and ashtray to recall the video’s original context. The staged absences made present through approximation suggest who is always substitutable when the switch happens, and the failure, or the great success, of the copy.

Vanessa Place and Kim Rosenfield’s “SCUM 1976 (2011).” Photo by Harold Abramowitz.

Bhanu Kapil’s “Schizophrene [Remix]” took place after the sun went down, allowing the Schindler studio to be backlit for her performance. The audience remained outside the studio to look in through the window. Kapil, in a symbolic rendering of a butcher scene, was the meat on the block. Wholly encased in red cloth, she moved in a contained rhythmic dance to a dramatically read excerpt from her forthcoming Schizophrene, bringing nation and its violences to bear on the question of home. For an hour, the recorded text played over and again as Kapil, captivating and captive, stretched limbs and torso, embodying questions of duration and endurance, compelling the viewer to ask: when does an onlooker turn and walk away from one who can’t?

The third day was hosted at the Fitzpatrick-Leland house. In an event described as the “performance of a conversation,” a diverse group of writers, visual artists, and critics joined together to reflect upon and further explore the previous two days of happenings. Cain and Carmody smartly coordinated the gathering, assigning each participant the task to bring and exchange an assigned question, comment, or object as entry points into the conversation. With the aid of a radio frequency interpretation system, what ensued was a lively and productively stimulating bilingual discussion with all voices offering readings, impressions, and reflections.

Both Sides and the Center is the latest in a series of inventive, larger-scale curated events from Les Figues Press, such as last summer’s Not Content, which continue to bring together and cultivate an ever-growing artistic community in Los Angeles and beyond.