Becoming in transit

Sun Yung Shin's 'Unbearable Splendor'

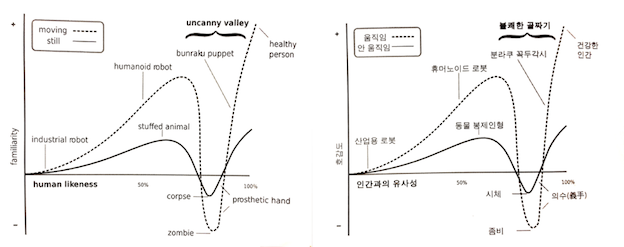

The term “uncanny valley” refers to the relationship between objects that appear human and the emotional responses they elicit, the degree of likeness of the former being traditionally assigned to the x-axis, while the y-axis describes the spectrum between repulsion and endearment. Although originating in robotics, the term has been disseminated through popular tech periodicals such as Wired to discuss in part the advances in computational power to simulate and reproduce the human form, from photo-composites (or “Photoshopping”) to computer-generated puppets in movies and videogames. The uncanny valley postulates that the more human-like a replica becomes, the more endearing to the observer it becomes, until it reaches such a level of human likeness that this endearment turns to dread. The increased use of motion capture, the practice where a person’s physical features and motion patterns are digitized and converted into computer assets, has helped blockbuster video games push the limits of verisimilitude in the representation of human beings over the past decade, as demonstrated in the digital reproduction of actress Ellen Page in the 2013 title Beyond: Two Souls. There is however only so much a polygonal mesh and tessellation — the topological process that allows a surface to become more complex — can do to increase the likeness of the human figure. Consequently, while the décor of the game seems directly extracted from archival footage of American suburbia, a certain plastic sheen remains on the skin and clothes of the characters, constantly reminding us that we are immersed in the digitally created world of a video game.

Invoking the various figures of the cyborg, Blade Runner’s replicants, Jorge Luis Borges’s Minotaur, the clone, the embryo, and artificial intelligence, the uncanny valley looms heavily over Sun Yung Shin’s Unbearable Splendor and its exploration of Otherness. The book is part of a lineage of other works that seek to explore the consequences of American adventurism and support of authoritarian strongmen following the Second World War, centering the narrative away from the white gaze one finds in Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, or the song “Rooster” by Alice In Chains, a lineage that includes Myung Mi Kim’s Under Flag and more recently Bao Phi’s Thousand Star Hotel, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer, and Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do. However, unlike the latter three, Shin’s narrative is fragmentary and inchoate. Like Bui in her aforementioned graphic memoir, there is a generational silence in response to Shin’s questions of origins and history. This generational silence is typical of the Vietnamese refugee experience, but, in Shin’s case, cannot be attenuated on account of her condition as a Korean refugee and its sociohistorical particularities. Quoting Eleana Kim, Shin describes the implications of becoming a “hojuk,” or “orphan,” within Korean legal and social structures, one of the few instances in the book where a Korean word is given a translation:

the legal “orphanization” process reconstitutes the adoptee socially in Korea. Within “the context of Korean law, she becomes a person with the barest of social identities, and in the context of Korean social norms, she lacks the basic family requirements of social personhood — namely, family lineage and genealogical history.”[1]

What is described in the book is ultimately a state of in-betweenness, as illustrated by the two Uncanny Valley graphs at the beginning of the book, one in English, the other in untranslated Korean (2–3).

Beyond the Korean War, K-Pop, and the ubiquitous technological devices of Samsung and LG, Korean history and society are largely illegible to most Americans. There are fewer movies about the Korean War than there are about the Vietnam War, for example. Bereft of scandal and images, the former is at best a continuation of the Greatest Generation narrative and its Manichean perspective. However, the consequences of the war are inextricably tied to Shin’s biography:

A few months after our birth, on August 15, 1974, Park Chung-hee, the military dictator of South Korea, who had declared himself “president for life,” was the target of an assassination attempt by Mung Se-gwang. This violent incident resulted in the death-by-gunfire of Park’s wife, Yuk Young-soo, and a high school student who was part of a choir performing at the ceremony. (36)

What is at play here is a project of recovery, an archeology, and Shin uses conceptual techniques to dig through and uncover the circumstances of her past, through reproductions of her orphanization paperwork in both English and (erased) Korean and quotation of works surrounding the aftermath of the armistice. But this orphanization document is Shin’s most personal artifact displayed in the book. There are no photographs of a mysterious woman who may or may not be Shin’s mother, or of a child in baby clothing like one would find in a W. G. Sebald novel. It bears repeating that Korean adoptees are utterly divorced from Korean culture and language, a condition highlighted by the recent deportation proceedings of Adam Crapser[2] and Phillip Clay. Having been raised in the United States from an early age, Shin was not privy to what followed the end of hostilities in the Korean peninsula, the military dictatorships, the student uprising, and South Korea becoming a nominal democracy in the late 1980s.[3]

In “The Other Asterion, or, The Minotaur’s Sacrifice (A Story),” Shin monologues through the titular character, in a move similar to Jorge Luis Borges’s retelling of the myth of the Minotaur in “The House of Asterion.” However, Theseus is largely absent in this second retelling, the murder of Asterion merely foreshadowed with “the blinding dazzle of a blade and small ball of fine thread, its delicate tail leading away from us” (34). Through the title and acquaintance with Borges’s prior story, Asterion is already known to be the Minotaur and is allowed to keep whatever sympathy he garners throughout the story, absent the plot twist from Borges’s retelling and the attending process of dehumanization through murder.

Yet, there still remains a sense of alienation and dissociation. Borges’s version of Asterion is, plot twist notwithstanding, a traditional story where the narrator is consistent from beginning to end, manifesting desires and aspirations that should elicit sympathy within the reader. On the other hand, Shin’s version regularly shifts from first person to third person:

Never let me go, I said to myself.

Never let me go,Asterion said to himself. (33)

The sense of self is unstable, bicameral in both Asterion and Shin. It is in transit. The third person implies a projection of the sense of self outward as if to attempt some form of understanding that cannot take place. Living in a place that does not recognize her as one of its own and seeking a connection to another that sent her away, Shin’s conceptual strategies give way to an analytical lyric where cognates collide with proximate phonemes, such as when the word “guest” is juxtaposed vertically with its etymology and horizontally along the dialect spectrum. Each iteration finds a different valence along those two axes: “friend,” “host,” “master,” but also “ghost,” “enemy,” and more prominently “stranger” (15–16). Those lyrical terms meander toward description, never reaching a meaningful totality, demonstrating a language in turmoil and a divided sense of the world, not only in English, where “abandoned and the re-en-familied, re-kinned, an adoptee is many things, including, I would posit, both a form of ongoing transit and a re-territory, a re-form” (41), but also through the occasional appearances of Korean fragments, some left in Hangul, some transcribed, but all illegible to the reader not familiar with Korean language and culture:

Facts Flesh ghosts

입앙 인니다

[bowing]

만 마서 반갑습니다. Mannaseo pangapsumnida.

It’s nice to meet you.

How should I address you? (43)

What is at stake throughout the book is an ethics of address. Now invoking the figure of the replicant from Blade Runner, which has also influenced our view of East Asia as a place of alterity and futurism:

16. I didn’t know I wasn’t human. My past was invented, implanted, and accepted. I’m more real than you are because I know I’m not real. (71)

This is a project of reclamation of one’s own humanity. Should one appear as human, be capable of independent thought, shouldn’t one be treated and feel as such?

1. Sun Yung Shin, Unbearable Splendor (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2016), 46.

2. Sang-hun Choe, “Korean Mother Awaits a Son’s Deportation to Confess Her ‘Unforgivable Sin,’” New York Times, November 16, 2016.

3. Ryan General, “Deported Korean-American Adoptee Found Dead of Apparent Suicide,” Nextshark, May 25, 2017.