An archive of feeling

A review of 'The Bigness of Things'

The Bigness of Things: New Narrative and Visual Culture

The Bigness of Things: New Narrative and Visual Culture

On a Friday night in October, a fine collection of people I do and do not know assembles in the ballroom of the Omni Commons for a marathon reading organized in conjunction with the New Narrative conference at Berkeley. The conference is titled Communal Presence: New Narrative Writing Today and feels aptly named. In this grand room, we convene together as a ragtag and motley crew, an intergenerational community built around shared desires to connect with one another, to experience the body and its emotions together, to throw our queer longings into the fray as one. New Narrative has, is, and always will be an ever-expanding community. Here, on this day, at this reading, we commune with one another, as writers and artists have communed in this space and others in the Bay Area for decades.

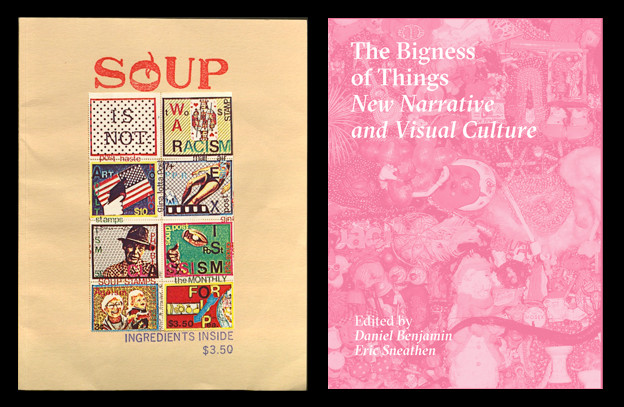

For the uninitiated, New Narrative arose out of distaste with the limits of Language writing, helmed by the San Francisco poets Robert Glück and Bruce Boone, who found Language writers too straight and too male. Formally named in Steve Abbott’s magazine Soup, New Narrative came into being as a force in experimental writing that reinserted subjectivity — particularly a queer subjectivity that would not exclude people of any identity — into a number of art forms, infecting writing as much as theater and visual arts, in fact growing through such cross-pollinations.[1]

The boundaries of New Narrative are vague. For a group formed by friendships and shared affects, by proximity and distance and shared distaste, by gossip, by the spaces afforded and made through queerness, how can one demarcate its edges, its borders? When I gave a copy of Daniel Benjamin and Eric Sneathen’s The Bigness of Things: New Narrative and Visual Culture (Wolfman, 2017) to a coworker, he opened to the images from the horror trash film Whatever Happened to Susan Jane? and told me he was somewhere in the crowd, an extra in the film. At the time, he had no idea his friends and collaborators would be considered “New Narrative.” They were merely his friends, artist and poet weirdos, each one with a story. They would show up at performance spaces, art openings, and readings, as supporters and collaborators. They were mostly queer, mostly punks, mostly only adored by each other, and a vast majority of them were lost to the AIDS epidemic.

The Bigness of Things brilliantly excavates the myriad forms that informed this writing and these friendships, the artwork and material remnants of a community that tied writers and artists together from the ’70s onward. While New Narrative has been remembered and reinscribed for its literature and its clear influence on autofiction and the confessional, this book of essays, which includes over fifty pages of art from writers’ homes and film stills, repositions the importance and archival value of the material: the gift, the trash, the scribble. And in doing so, it performs the kind of holistic work necessary to unpack this movement still in motion.

Daniel Benjamin, Eric Sneathen, and an astounding troupe of essayists (Matt Sussman, Brandon Callender, Jamie Townsend, Stephanie Young, Ismail Muhammad, Syd Staiti, and Brandon Brown) have done an impeccable job disseminating archives and resonances, excavating the threads that connect the literary to the performative, the performative to the material, and all the refuse that lingers from friendships and shared affects. Separated into sections on visual art, printed matter, and film, The Bigness of Things gets into the roots of New Narrative formations and does valuable work in expanding queer political memory.

Matt Sussman’s work on the visual art found in the collections of Kevin Killian, Dodie Bellamy, Robert Glück, Bruce Boone, and Jocelyn Saidenberg — as well as his curatorial work for the exhibit that coincided with the Communal Presences conference, Objects of Mutual Affection — explicates what it means to live with art. Looking to the art-filled apartment as more than a sanctuary or private realm, as a space inseparable from history and the workings of time, Sussman troubles the distinction between collector and collected in much the same ways New Narrative writing complicates the “I”of writing. In these apartments, artworks are not as much passive objects as they are active nodes in the formation of communities; in New Narrative writing, the “I” is similarly disturbed, not as much a singular entity but rather a vehicle for connection, an explosion of subjectivity, an extension of the self to an audience, its subjects, its comrades.

As Sussman’s work identifies the agency of art in so-called “domestic” spaces, Graham Holoch’s photographs of these writers’ collections bring the slightest nook to life with the sensory ecstasy of mixed plastics. Above Bruce Boone’s mantle, a Jamie Holley assemblage marks the shrine to a dumpster diva, reorienting how one encounters the space of a living room and how one might go about this act of “living.” In his study, Jerome Caja’s Untitled (Priest Fucking Altar Boy) rests next to a framed photo of a small dog, in front of two Philip Whalen books. There’s something beautiful about getting to witness not only the material components of an author’s art collection, but equally the libraries that subsume such a collection. Celebratory collages share space with the books of fellow New Narrative and small press poets like Renee Gladman, Barbara Guest, Kevin Killian, erica kaufman, Samantha Giles, Robert Glück, and an array of Loeb editions, art books, manuscripts, journals, friendships across texts.

The true cross-pollination happens when the art orients toward language, as seen in Brandon Callender’s work on the early gay DIY journals Sunshine and Sebastian Quill. Ephemera probably owned or flipped through at some point by queers of the area, these journals examine the sexual space of the written word and impart valuable lessons in unlearning heteropatriarchal conceptions of sex and identity. In printouts like “How to get Fucked and Like it” and “How to be a Hero of Homosexuality,” queer journals offered queer readers fundamental advice not only on sex but on self-conception, on the political orientation inherent in queer sexual positionings. The object of these writings is reeducational, rooted in issues of consent. As Callender quotes one advice columnist from Gay Sunshine, “we need a lot of reeducation of our pleasure centers” (52), and later: “It’s not just a cock in a dead receptacle, but a two way thing … sexier because you are paying attention to each other, and fitting in together more.” With this language housed next to orgiastic comics not nearly as Tom of Finland-esque as a Where’s Waldo of boys sucking each other off — small, connected bodies indistinguishable yet joined in an expanding amoeba of homo-love (50) — Callender reads the language and space of “How to get Fucked” as the agonistic formation of common lives, the orgy as the site of communality as much as distance. A kind of sex where we are together as much as alone. Queer journals offered the space to reconceive queerness as much as queer communities, and to articulate the socio-sexual politics of communities.

While Gay Sunshine and Sebastian Quill catered to gay male experiences, journals like HOW(ever) — which envisioned itself as a place for neglected women poets — and Renee Gladman’s Clamour, a self-described dyke zine that foregrounded women of color, produced alternate communities similarly oriented against the white-straight-male hegemony of art production and personal conception. Stephanie Young’s work on HOW(ever) articulates the space of the mag as a “threshold of visibility” (72), where ideas, working notes, and explicitly nonacademic writing of any kind could be shared with one another through an “alerts” section that aimed to reach outside heteropatriarchal restrictions on academic thinking and critical writing.

In these testaments to queer life and shared ephemera, one not only sees queer past, but its future potentials. These archives hold blueprints for future possibility: each piece of refuse a monument to future affects; each medium a platform for new dalliances, new disruptions; each manifesto a possible intervention to the present. This text is self-conscious, reflexive in its use of the archive; these essayists have not only touched upon queer memory but have been touched by it in turn. The writing of this text enacts another layer of relationality to a history, tying the essayists to the lived body of New Narrative.

In effect, this produces the kind of queer resurrection, or even resuscitation, put forth by Carolyn Dinshaw in her seminal text on how historians might “touch” bodies across time, Getting Medieval. Dinshaw, who looks to Barthes’s S/Z and Michelet, conceives of the affective connection made between author and text as a kind of longing across time, a reaching backward that equally afflicts any future output; as “the historian exists only to recognize a warmth,” the documents that are produced by said warmth carry with them “a kind of residual memory [une rémanence] of past bodies.”[2] Remanence is one way of figuring the state of New Narrative; the magnetism of loved ones and collaborators lost to the AIDS epidemic remains in those who are still here to write, and in those who, through writing, grant critical attention to the New Narrative movement.

The Bigness of Things is deeply rooted in this history, and charged by this magnetism. The essayists are no strangers to remanence, more interlocutors than academics set at a distance. New Narrative lives on through these essayists and the work they do in larger print/publishing/artistic endeavors. Jamie Townsend’s mag Elderly is a prime example; in their essay on Steve Abbott’s Soup, Townsend makes clear how influential Abbott’s journal was on their current editorial ethos. Or, more directly in line with Dinshaw’s reading of Barthes, Syd Staiti notes how they were “rewritted” by the “I” of Palema Lu’s Pamela, which, as they note, fundamentally changed how they “thought about the act of living and writing from within the bounds of the text” (93–94).

Townsend ends their essay with Abbott’s opening to Soup: “Etre dans le petrin! To be in the soup!” (68). This phrase has been ringing between my ears since I first finished Townsend’s essay. What does it mean to be in the soup? In the thick of it? Slowly melding, expanding, releasing, infusing with broth and other soupy elements? To think of ourselves newly positioned inside this ever-expanding amalgamation of bodies, liquids, remains, and additions, can we conceive of this moment in New Narrative, and this text on New Narrative, as a new recipe in the literary test kitchen, as an invitation for potential future disruptions? To be in the soup is an active call for participation, to lose neat boundaries of the body, to allow the “I” to crumble or at least fundamentally change our own “I,” to let histories sweep us into futures, to enable us all to seek out the bigness of things, their largesse, their possible expansions.

Of course, as Brandon Brown’s “Trash Masterpiece” reminds, the city of New Narrative — of Dodie Bellamy’s The Letters of Mina Harker, of Bruce Boone and Bob Glück’s famous walk in My Walk with Bob, the city of Whatever Happened to Susan Jane? — is not the San Francisco of today. Tech has taken over; it took over a long time ago. What do we do? Dwell in a kind of nostalgia? Or, as Brown reads in the final scene of Whatever Happened to Susan Jane, do we start over? Then, as now, life sucks, but there’s still some fun to be had. Rip it up and start again, with the pages of last time and the times before.

1. For more on the origins and definitions of New Narrative as both a social locus and a writing context, see Robert Glück’s “Long Note on New Narrative.”

2. Roland Barthes, Michelet, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1987), 81; Roland Barthes, Michelet par lui-même (Paris: Seuil, 1954), 73, qtd. in Carolyn Dinshaw, Getting Medieval: Sexualities and Communities Pre- and Postmodern (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999), 46.