Antenna openings

A review of 'Late in the Antenna Fields'

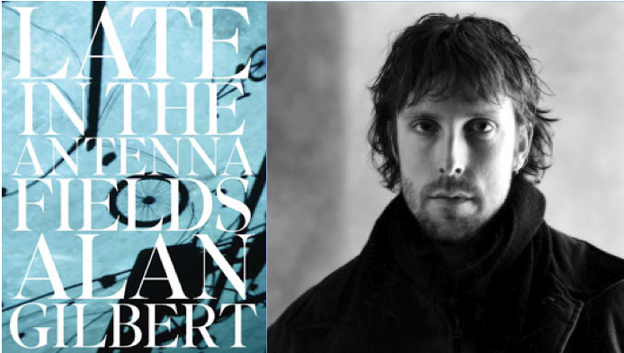

Late in the Antenna Fields

Late in the Antenna Fields

Alan Gilbert’s first full-length collection of poems expands on the notion of “creative resistance,” explained in Another Future (his 2006 study of poetry, art, and postmodernity) as a commitment to “hope without holding play as an end in itself.” Late in the Antenna Fields (Futurepoem, 2011) pursues this resistance by relating a large swath of cultural and personal phenomena, thereby arresting the endless spillage of images and tropes that so often compose the chaotic drift of postmodernity. Gilbert doesn’t let the formal elements of his poetry dictate creative logic. Form turns out to be but one imaginative possibility of a poetics that often stresses the performative over the literary. The “fields” of his title suggest not only the wide and disbanded twilight horizons of contemporary culture, but also provide a sense of larger creative fields — an array of discursive possibilities in which form adheres to other cultural (and rhetorical) elements that situate ethical procedures. Neither purely formal in their actions on the page, nor conceptually designed for an imagined audience’s required submission, a committed cultural performance gives these poems a somber and solitary edge.

A reader, however, must look hard to find differences in Gilbert’s writing from the experimental procedures used by other contemporary practices associated with a visible avant-garde. Gilbert theorizes this difference by reflecting on audience in Another Future. If the “open text” is truly open, he argues, “then why is it supposed to function in the same way for all readers, however different their backgrounds? As British cultural studies audience response research reiterates over and over again, different audiences respond differently to different cultural products; they even respond differently to the same cultural products at different times.” Responding to Lyn Hejinian’s definition of an “open text” as something “open to the world and particularly to the reader” and that, importantly, “is generative [of meaning] rather than directive,” Gilbert agrees that a “closed text” like an advertisement can provide “conventional modes of communication [that] negate dialogue and reassert more forcefully than ever an author’s authority and dominance over the reader.” Somewhere between both closed and open texts, Gilbert seeks a theory of writing that resists “mere” models of communication and the manipulations of desire associated with closed texts, but that also acknowledges a more complex ethical relationship between author and audience. An audience, however, needs something to grapple with, something that provokes their reflection, invites curiosity, drives them to action, or to better comprehend the world at large. What the closed text/open text discussion brings up, however, is a way to theorize relationships in texts between diverse parties of committed participants. Whether it’s the transparent emotional charge of lyric poetry or the self-interfering procedures of Dada or Oulipo, discourse is situated for an audience that is already shaped, in large part, by cultural regimes, ideological divisions, personal histories, and institutional affiliations. For the poet concerned with audience, writing is necessarily relational, reflexive, and frequently tested in its authorship to understand how words perform for others.

A poetics of documentation lets Gilbert shape his writing as performances on the page designed to invite readers to speculate on larger cultural phenomena, going beyond the concerns of the author, the situated conditions of the audience, or even the aesthetic formal possibilities of the text. What’s at stake in documentation for Gilbert are large cultural referents and how they interrelate in poetry with his own creative and introspective life. He challenges the turn to language by drawing on cultural phenomena that have been distributed through diverse discourse situations, and his recontextualization submits new perspectives for readers to consider. An ethics of investigation and documentation adheres to a writing task that manufactures possibilities, critical awareness, and new representations of the complex mashups of cultural hybridity.

Despite his concern with material culture and its uneven distributions, Gilbert constructs a voice, or voices (often pushed to limit points of flatness), that readers must accept, puzzle over, question, or even resist. It’s the voice of the hip and artfully aware global (Western global) citizen, performing various modes of subjectivity in a process that documents contemporary cultural discourse through multiple perspectives. In “Coolant System,” the constructed ethos of the poem adheres through a steady voice of reportage:

Some people are awake in the middle of the night.

Some are at the bathroom sink rinsing and spitting.

There’s a PowerPoint presentation for just about

anything, and a personalized ringtone to alert us

when the war is calling — it’s the sound of beds

being dragged across an orphanage floor.

The amplification of imagery moves attention from mundane toilet routines to the effects of war, mediating this move through the ubiquity of PowerPoint, a tool of business communication. The steady stitching of imagery arrives through a subjectivity that never rises above the material image to mediate or comment on what’s passing. Instead, it seems almost medicated, submerged in an evenness of appeal regardless of the near terror the poem invokes. “The next ice age,” Gilbert writes, “will fill the rivers with antifreeze. / It’s the midway point of a sugar packet’s half-life, / spoonfed in timelapse with porn made to order. / I still briefly pause when I hear an airplane flying / low.”

While it’s sometimes difficult to fully appreciate how Gilbert’s theoretical claims for poetry differentiate his writing from other contemporary practices, the work provokes readers to consider a wide array of cultural material. In “Go Solar,” for instance, he writes:

Cartoon characters don’t age, they get canceled.

A lifeguard missed the shark attack while reading

the articles of impeachment. After years of enduring

such a fucked-up situation, the question of blame

became relative, and longevity gets more difficult

to spell. Is the context going to be love, the impossible

imagination of mourning quickly?

While provocative images wind through the poem, the sharp, paratactic turns and the unmediated movement from cartoon characters to shark attacks distract from the more compelling question the stanza offers. This is followed, however, by a striking assertion of shattered feelings and derailed memories in the contorted subjectivity of the projected author:

Some of my best friends are machines tracing dust

back to the body, the night to the sun searing

a massive oil spill scooped from backyard swimming

pools with spatulas and patched with hair dryers

applying decals advertising the local speakeasy

serving a rubbed-off shine backed by a bucketful

of teeth.

The long, unbroken sentence, along with the tension of figures of decay and commodity culture, move the poem from undifferentiated images of cultural diffusion toward a more passionate claim about how change or loss is comprehended in a postmodern context where nothing remains still, and where decay and the loop of memory both compete in the eternal renewal of commodified forms. In “Spitting Image,” Gilbert pursues a critical vision of Western culture through a pronounced syntax that draws close the imagery governing his imagination. Poems like this are distinguished for their attempt to organize perception according to unsentimental, but nonetheless emotional, tensions. The extended sentence, and the childhood significance of the “you-said / I-said” / tire swing” situate the juvenile culture Gilbert is critical toward, while also exposing a voice, however constructed, that can’t help but seek order out of the chaotic spam of contemporary life. He writes:

All the toxic runoff

drained into a green pond

behind the house

where the you-said/I-said

tire swing slowly

pulls loose from

its timber moorings

whole it’s nighttime

with the windows open

in any kind of weather

eroding skeletons

pushing up through

carpets and tack strips,

because love is what

undoes us.

The cliché of “love is what / undoes us” is amplified in the next stanza, where Gilbert announces, “I’m a collection / of flesh and implants / dropped in the mail / each day to the hummed / Miss America pageant theme song.” By organizing competing tropes of subjectivity in his poems, Gilbert is able to use clichés that take on new significance in the arrangements of the poem. In a period where irony and cliché often form the basis of communication (consider all those Super Bowl adverts, built on clichés and cheap sentiments that reinforce the loony notions of who “we” are), Gilbert’s critical inventory and redistribution of commodified imagery let him perform subjective experiences in order to disclose relations that evolve in the hybrid drifts of contemporary culture.

What should Western poets do in a period where the intensity of the daily barrage of advertising, the paucity of public display and speech, and the transfer of regional labor practices to global network centers disorient and disturb relationships to cultural or political practice? If postmodernity is a mashup of prior forms, renewed forever in a freeform universe indifferent to all claims of truth, should a poet imitate the state of things? Find forms that compete or criticize her world? Or develop ironic poses and distancing techniques that preserve the poet even as she manipulates the book markets that necessarily reproduce and distribute the formulae of perception for others. In an era of rapidly increasing authorship, the notion of audience comes into question. We’re all producers, all authors of our insightful experiences and perceptions. We read as thieves and judges, in quick, predatory bursts, because this is how one survives. Knowledge and communication perhaps seem inconsequential compared to the perceived circulations that give shape to our social imaginaries.

The Sophist, Gorgias, famously announced the impossibility of knowledge and communication. Even if we could know something, he argued, it would be impossible to communicate what we know. We’re left with an endless game, at play in linguistic discourse, appealing by whim to others based on the drug-like elixir of language. Plato’s response to this dilemma was to pursue a kind of ethics over communicative force. What are the responsibilities of the writer to a text or to an audience? Late in the Antenna Fields, with a similar set of concerns, attempts to organize a poetics that is ultimately ethical and committed to reinforcing strategies of perception in readers. How are we to respond to proliferating cultural formations, a globalized economy, and decayed regional experiences? If knowledge or truth is relative, and language unstable, what does poetry provide to make itself useful and permanent on the cultural landscape? Gilbert’s performance of social weirdness and contrast lets him interrupt the endless flow of things with focusing incidents that vocalize old fashioned human feelings of anxiety, fear, hope, and desire. Unfortunately, the subjective voices and performative utterances often strain the register they intend to critique — a present in need of more ample vision and creative action. A poem must still have life, even if the cultural phenomena that contextualize everyday experience circulate with dull and steady certainty. The poem can’t replicate this without losing its abundance or its evocative potential. “Sometimes,” Gilbert writes, “the only weapons are words during / a trip to the quarry with its mine-disaster machines / slowly scraping // along the edge of commands that some Americans / have for other Americans, a cracked / ruler drawing attention to chalkboard maps and / framed pictures.” In a dizzying succession of images, Gilbert seeks to order his puzzle of relationships, and to characterize cultural experience in the early twenty-first century imaginary. This ambitious art doesn’t always come together, but with other new books (I’m particularly thinking of Farid Matuk’s This Isa Nice Neighborhood [Letter Machine Editions, 2010]) Late in the Antenna Fields, with its set of major concerns, attempts to organize a poetics that is ultimately ethical and committed to reinforcing strategies of perception in readers.