Nina Zivancevic's 1983 interview with Charles Bernstein and Douglas Messerli, with a new postscript by Messerli

audio and text

This interview was first publlished in the Belgrade literary magazine, Knjizevnost, and in Sagetrieb's Winter 1984 issue (Vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 63-78).

The undedited audio of the original interview, from November 5, 1983, is avaialbe on PennSound:

(2 hrs, 18min): MP3

NZ: Since this interview is primarily for the Serbian audience, who knows little about the contemporary American poetry scene—at least this side of contemporary American poetry—I would like to start from the beginning. Although the work of some contemporary critics such as Barthes or DeMan has been translated in Yugoslavia, I do not see any literature to proceed or accompany such criticism….

Charles Bernstein: This is also true here, aside from the small alternative and independent contexts of publishing. Critics such as you mention are published and publicized more than the poets I am interested in, although you can find their texts also, if you make the effort to seek them out.

NZ: Do you agree on this, Douglas?

Douglas Messerli: Oh, certainly, although that’s hopefully changing as publishers, like me, are beginning to get more forceful and aggressive in publicizing our works. But it is true that are not in the general public’s consciousness.

NZ: O.K., your work and Charles’ prove something different, so I am interested in the actual history of your writing. You remember that Olson said once that the history of a word started when Europe and Asia divided; so when does the history of your word start?

CB: The first thing I remember was my mother saying….[laughter]. It’s such a broad question….

NZ: In other words, when did you start writing the way you write now; what changed your mind that you started writing quite differently from….

CB: Actually I am an odd instance in the sense that I wasn’t doing a conventional writing which I then renounced and started writing in an unconventional way. I was interested in something like the writing I am doing now before having written anything much or published anything, so, in fact, I’ve been on this monolithic track, and for that reason it’s hard for me, without being reductive, to pull out what it is that interested me from what interests me now or lead from here to there or there to here, that kind of historical background you construct afterward, and then to sort of pull out where my biography comes in (being born into a very specific cultural situation and hearing that first or through that first and then finding an otherness in writing not of this same origin, that told me or began to tell me what I needed to know by telling me all that I could not know and then begin to). So one thing that was or is important was to understand writing as something beyond simply philosophy, criticism, journalism, poetry; and understanding that has to do with an experience of reading. I would situate my work as a writer primarily in the experience of reading. And it wasn’t so much writing values that I became interested in, but reading values—ways of reading different kinds of things, the different kinds of things to read, and the permutations of that. Meanwhile, by the time I was in high school there was this large-scale cultural critique taking place that I grew up into. It wasn’t just that Lyndon Johnson was lying about the Gulf of Tonkin, since this would not have been such a surprise. Because you couldn’t get to the truth just by reversing any set of government lies—there was a web of deceit and manipulation that wasn’t just in the assertions but in the syntax itself. Neither the lies nor the truth as able to be contained in the “face-value” language because the ideal of “face-value” language was itself an instrument of deceit. So this is then mixed in the mind’s inscrutable blender with—what?—well I might have been reading Joyce or Beckett or thinking about reading Proust without necessarily doing so; so I would be plowing through Ian Fleming’s books, reading the instruction to dialers section of the phone book with a kind of Talmudic attention, as a preface to the general listing of names (can you believe that there are three people with the name of Struggle this year?). But certainly Douglas and I shared that generation experience of having certain kinds of normative values questioned at a general level, and because I spent most of my free time reading or watching TV or going to the movies, this spilled over into my sense of reading texts (if you’ll allow an episode of the Honeymooners as a text). Also, I began to be very interested in that time in Thoreau, in Dickinson, in Hawthorne, Melville, as well as in, oh—Sartre, Kierkegaard, and to see those interests—certainly in philosophy and literature—as interrelated.

NZ: So, did you get acquainted with Sartre’s political stance?

CB: Oh, yes, it all comes together, that’s what I’m saying. But well, when I read The Age of Reason when I was 13 I did not know what a homosexual was! Ian Fleming had not prepared me for this! Reading Sartre told me there were homosexuals—people previously inaudible or invisible to me, that there were worlds outside what I knew from the face value of things. This is an example of how literary/political/philosophical things would come together for me, in questioning the overly centric or normative traditions which, well I can’t say I was being exclusively taught in school, since I had teachers who were sympathetic to this perspective themselves. I remember a very profound experience about that time—a history teacher writing on the board a line from Beckett—“Bun is such a sad word is it no? And man is not much better is it?” (as I remember it). And he said, apropos of nothing, isn’t this an extraordinary two sentences—but what does it mean? Just thinking that there was some relation between the way the word “bun” sounded and the way the word “man” sounded that was beyond any relation of what either word might “mean” but which then in fact linked back to in fact what that might mean. So my interest was always in writing which didn’t necessarily … Wasn’t Verse. In fact I was not that interested in the English verse tradition until much later on (although to say that is really an oversimplification since I had read Blake and, of course, Shakespeare with a good deal of enthusiasm at the time I am referring to). But for the purposes of this line of argument, let’s say that I was much more interested in American prose, philosophical and fictional, and European prose, philosophical and fictional, of the nineteenth and eighteenth century. When I did become interested in poetry—it was with a sense that this was—and in Dickinson I saw this very strikingly—a particular means of dealing with philosophical and political and linguistic and cultural concerns in terms of the medium of writing itself. That’s a very complicated way of answering that question, but….

NZ: How about Lewis Carroll?

CB: Oh! I love Lewis Carroll. Of course I had read Carroll early on like everybody else. I can’t say, though, that I appreciated the greatness of the “Jabberwocky” or Humpty Dumpty on meaning until many years later. But my point is that I’m not mentioning everybody I read, that the value of such a list is highly suspect.

NZ: Douglas, what was your favorite book in high school?

DM: Oh, it had nothing to do with a favorite book, but was much like Charles’ case. I wasn’t fond of poetry, and my reading habits had a lot to do with my upbringing, which I felt was extremely isolating. I grew up in the American Midwest, in Iowa, and as a child I began creating a sort of imaginary world, a world which had a lot to do with theatricality and theater. I also was very much taken by fiction, even before I entered college. But it was in the sixties, when I was in college and participated very actively in the University of Wisconsin protests against the Vietnam war in 1965-1967—those were the years of the big protests—and discovered that I, myself, was one of what Charles has described was one of Sartre’s homosexuals, that things came together. I was a philosophy minor: Kierkegaard I liked very much, not so much the Existentialists such as Sartre, but Kierkegaard in particular, along with my love for fiction. I liked traditional fiction, but was even more attracted to the writings of Jane Bowles, Djuna Barnes, John Hawkes, Samuel Beckett…poetical fictions. Yes, Kierkegaard’s philosophical fictions appealed to me a lot. But it wasn’t until I finally went on to graduate school—after having left the university, living in New York City, and returning to college—that I actually discovered what poetry was. At first, just to get them under my belt, I began reading poets of the Modern tradition—Eliot, Crane, Lowell, etc.—and wasn’t very excited by them; I couldn’t really respond to their writing. I was still trying to write fiction—but a very strange fiction by that time; it didn’t fit into the Modernist context, so I was having a difficult time of it. It wasn’t until I took a seminar in contemporary lyric poetry, taught by Marjorie Perloff, that I discovered there was a whole other poetic tradition—a tradition from which, in a strange way, I had been “protected.” I discovered poetry, in that respect, from poems such as John Wieners and Frank O’Hara; then I filled in with Rimbaud, Pound, Williams, Stein, Apollinaire, Emily Dickinson, and some the poets Charles mentioned. It was at that point that I realized why I hadn’t succeeded in fiction. I had been trying to write a fiction of philosophical intelligence in novel form—the wrong genre.

NZ: You said that people like O’Hara or Wieners got you interested in poetry, but where was the diverging point where your work became different and came to something which they call “Language” poetry today?

DM: It wasn’t that I liked everything that Wieners and O’Hara were doing, they offered the new possibilities I saw in poetry. But I wasn’t as much interested in what they were doing with poetry. What I did like was the way they used a kind of collage method and put images on top of each other or lined up radical similes side by side, because that allowed from a kind of quick movement of the mind. But I was never interested in the personal outpouring that you find in imitators of their work. I was, perhaps, interested in everyday language (the American syntax, maxims, and neologisms were what attracted me to figures such as Stein and Williams) but not exclusively. What happens when you start writing poetry is that you find what most interests you; you come to own concerns. I might have begun by imitating O’Hara, but the result was radically different. What they poetry did for me—as did the poetry of Stein and Pound—was to open up poetry in general, to show me that I could write a poetry that wasn’t “over there”—structurally pure, objectively voiced, and thematically universal. Rather, my theatrical, philosophical, and narrative concerns could be dealt with in a very tight linguistic play of text…. Then, I started reading my contemporaries, who influenced me far more than any of the poets of previous generations. And at the same time I was reading the theories of Pound, Williams, and Stein, so it all began to build up. And I finally understood that it wasn’t just “poetry” in which I was interested, but the whole issue of language. What people generally describe as “poetry” is so delimited; but “poetry” for me became an act that included far more than using words in a compact or crystalized manner of making a beautiful object of words or expressing how you felt from day to day; industry does all of those things better. For me poetry became simultaneous with the mind trying to understand itself and the world around it through the only medium—language—through which the mind could come to know and understand. And that opened up poetry to include everything—to include not just the kitchen sink but the sink and the state of Louisiana [laughter].

CB: I would have to … just to. One of the reasons I said about that Kierkegaard thing in respect to what I understood you to be saying is that partly what interested you in Kierkegaard isn’t so much the theory preceding the practice but Kierkegaard’s particular literary practice….

DM: The approach to the….

CB: …which isn’t a theory influencing you, but actually a literary form—in translation, perhaps, but ….

DM: But it was also a theory ….

CB: Also, but you can’t ever take those things apart….

DM: Exactly, you can’t separate them. It was that kind of excitement—that is wasn’t just a theory “over there”….

CB: It wasn’t just disembodied ideas.

DM: It wasn’t Kant, it was something else.

CB: Of course, I consider myself very influenced by Kant [laughter].

NZ: Charles, could you add something on influences?

CB: I think there is a great danger of making things seem coherent that aren’t easily explainable. I am familiar with things in 1983 that I can understand historically quite well, various developments within contemporary writing, my own and others. I see the precedents and I can construct convincing literary history. In other words, I would almost say that I am very influenced by writers I have only read recently. In other words, I should have been … and now I see, yes, in fact, that those are the crucial people that could link … but in fact I happen not to have come upon them. I mean to say that things get filtered, different people read different things and you can pick up something which is derivative that somebody else has done and that gives you certain information even though it’s not the “original,” but it tells you about a certain kind of practice. So I am constantly filling in my poetic, literary, political, theoretical history in a variety of different ways. And I reject the Poundian noting of some fixed pantheon of sources or even the Olsonian idea of mastertexts that can establish or ground the writing project. Which is not to say that if you live in Colorado you could ignore the Rocky Mountains, which, for my ears, as far as the horizon of the century goes, would translated into names like Stein, Wittgenstein, Freud, Joyce, Proust. That’s as much a part of the landscape for me as the Russian and Chinese revolutions, the holocaust, Hiroshima. Meanwhile, somebody like Jerry Rothenberg was producing anthologies that literally opened up new worlds for me, other landscapes some of which were quite literally exotic while others were in fact whole American wildernesses that had been hidden from view by the painted scenic backdrops of official verse culture that artificially foreclose our literary heritages.

NZ: What did they mean to you, those anthologies?

CB: Well, Revolution of the Word there was a mapping that went behind, in the sense of filling in the background, a collection like Donald Allen’s New American Poetry, which featured people like Eigner, Creeley, Olson, Spicer, Ashbery, Kerouac, Duncan, Ginsberg and so on. Rothenberg had a more formally radical program—to assemble work specifically “revolutionary in structure and word” and within this context included not only more innovative work by Williams, cummings, and Pound than those by which they are usually represented, but also included H.D., Mac Low, Oppen, Loy, Riding, Zukofsky and a number of other people still virtually unknown such as Abraham Lincoln Gillespie. Also, as to representing work “outside” established traditions, while Allen’s book had virtually excluded women, Rothenberg’s makes the almost implicit claim that a number of women poets were in fact too radical even for The New American Poetry, even though Rothenberg’s book covered writing in the era preceding that covered by Allen. So here were numerous instances of an American writing that in many ways made The New American Poetry look tame in terms of its attention to the actual space of the page, to the conditions of verbal language itself as the medium of poetry. Then when you get to some of Rothenberg’s other anthologies, like Technicians of the Sacred and The Big Jewish Book, you begin to see how writing worked in other types of societies not by making its textual qualities disappear but in contrast by tuning in on exactly those “plastic” dimensions of language. So these were all different traditions of writing that did not involve directing the reader or hearer to something happening outside the text but rather focused on the actual duration being inscribed in the text, as the text. And the techniques did not include mimicking an idealized speech but rather repetition, cut-up, rhyme, alliteration, and other means of making the medium itself tangible.

NZ: Could you tell us something about “language” writing? What is it? That is, I notice that too many people are confused about the term. And then I learned that it was a magazine (L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E) that you edited with Bruce Andrews in the seventies.

CB: Is Douglas going to go with that?

DM: No, you go ahead…. Well, do you want me to…. Ya, I’ll go first because Charles is probably much capable of answering that.

CB: Or incapable.

DM: Or incapable as the case may be. First all, there’s no such thing! It’s a term that partly through the creation of people like Charles and Bruce Andrews and others seemed to be one way of beginning to describe something they had in common, although they are radically different poets. And then it became a way of describing concerns that a lot of poets had in common, and was an emphasis, a focus—not a way of writing, not a method, not even an approach. But the emphasis was somehow not a thematics, for instance, nor on a separation of the thematics from the process of writing itself. It seemed to be something that put more emphasis on the very way in which language interrelated and was created and mean—the way it made meaning and allowed for meaning—and that focus on the very process of language-making itself, of the mind involved in that activity. It seemed also appropriate to a certain degree to describe a generational concern. For instance, you might find that Gertrude Stein, if your wanted to talk about her work in the most formal sense, was one of the greatest of all “language” poets; but she wouldn’t be described that way because the term seems more appropriate to describe something with which our generation was/is particularly concerned. However, there has been a danger in all that because you asking what does that mean and other people confusing it with some sort of monolithic force that they’ve got to put down like a revolution on Chrome Avenue where the Haitians are impounded, and people beginning to apply it like it is some kind of generic term or beginning to define different poets in terms of that. I can’t imagine any more radically different poets than the so-called “language” poets in terms of what actually gets produced. It’s the shared concerns that are the focus; that is what the world “language” is all about.

NZ: What was the literary climate when people like you and Douglas began your work, Charles. How did people react to your work here, because I read in some sort of “guide to Charles Bernstein [The Difficulties, vol. 2, no. 1], in its introductory note, someone said that “not many people did understand” your work?

CB: Or as someone recently wrote, “Charles Bernstein has had a whole issue devoted to his work, but nobody know who Charles Bernstein is” or who almost any of “us” is—from Zukofsky on down. That is, for almost all the poets that I’ve mentioned so far, and to a similar extent for my contemporaries, there is very little “literary climate” at all. Poetry, regardless to the type, is a very marginal activity. So when you’re talking about something that is on the margin of this margin (which is not to say that it may not be a central cultural activity if or when it is recognized as such) … one does not get too much response beyond the relatively circumscribed community of writers and editors actively involved, no response that is from a larger literary world or “public,” although there are squeaks from those parts from time to time, and I find more and more actually. But I would say in general — with a few tokenized exceptions — the above-ground literary establishment organizations in the country have systematically excluded the whole active tradition of American writing from Stein to the present.

DM: I agree with that!

CB: And so, in that sense, this is another episode of that. However, within the poetry community, the significant fact is that L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E and a number of related publications provided forums for lots of different people to comment on lots of different people to comment on lots of different things. I’d like to think that what held the magazine together isn’t any kind of centrist belief — because I don’t believe in a core idea about anything, as I’ve been saying — but rather the fact that we brought people together who weren’t doing things within the dominant, officialized modes of syntax and vocabulary and so on, and when something is based on being decentered in that way, that it is because people are not operating within the highly conventional rigidified codes, then they don’t really have anything in common. And that’s what’s interesting to me, but it also makes this issue of what is x, in this case where x is “language writing,” a difficult one to answer, and why there is so much confusion as to whether it’s a genre, whether it’s a generic term, whether it’s style, how it can be an extension of a number of different traditions, or that I’s are everywhere — in our mouths and in our ears — and yet no one where. Still, it’s important to acknowledge that L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E did publish primarily people with a very roughly homologous cultural and class affiliation — that is anglophonic, college-educated, middle-class, though often downwardly mobile, with obvious and significant exceptions of course.

NZ: What is the influence of critical theory on the poetry?

CB: If I wanted to be arrogant I would say it created the critical theory, but that in fact isn’t true because they are synchronic developments. It’s useful to note that many of the poets we published in L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E are actively hostile to the style of most critical discourse and that much of the important work has developed in the context of a repudiation of such discourse as it is normally practiced (i.e., written). Anyway, there is no theory that adequately discusses the developments within American poetry except for our efforts as poets, both now and in past years. In fact much of work coming from those efforts is, to my mind, more telling than any of the recent literary theory in this country that deals with similar issues such as “textuality.”

NZ: Well, hasn’t that always been the case in the history of literature, that poets such as Pound were the best commentators on their work?

DM: Some poets have done that and some, like Ashbery and O’Hara, were not interested in that type of investigation.

NZ: Because they were not creating a new poetics or they were?

CB: They were! And that’s just the point! I don’t believe that critical or theoretical thought can or should be subservient to poetry. And I’m totally against the idea that poetry is somehow a richer field of investigation. Certainly, there are a number of nonpoets doing work at a level with any poets, and vice versa. In the significant cases it’s never a question of the cart-before-the-horse: “it’s the poets who are making the read discoveries” or “it’s the theorists who make the poetry possible.” It’s neither one nor the other; it’s a symbiotic relationship or it’s an adversarial relationship or just independent developments. But the idea of trying to piece together which came first is a false historicizing which is almost impossible to break away from without seeming unnecessarily obscure or, as I am often accused of, not wanting to be pinned down. Because there are no simple answers to these things and while it’s easier to understand simple answers, I don’t have them. But certainly within academic criticism at this time there is an undervaluation of the theoretical contribution made by the developments within the poetry that I have speaking about especially since this contribution if recognized would undermine the style of that critical writing, call the interest values of that style into question. You can talk about textuality until you’ve green in the face but that’s not the same as making texts responsible for themselves, such as those of Thoreau or Walter Benjamin or Ashbery. Now, I happen to be very interested in socialist critical thought. A lot of work in this area is very important but I don’t feel it is necessarily influencing what I do or that I am influencing what it does—although I might find it encouraging or confirming. But it’s something different. It’s a different aspect of critique and that ongoing critique is a project that I think poetry and poetics and fiction and other modes of writing and talking can participate in. And in that sense to me the important issue is to raise questions about what a social critique can do and how can it be furthered, but not to be simplistic and dismissing of the work of many critics that is independently significant. But really I’m putting it all upside down because it’s the new theoreticism that is dismissing the poetry while it would do better to learn from it: learn that there’s no point in writing a secondary text; all texts of whatever genre benefit from necessity. And if you’re going to do literary theory, then let someone like Benjamin, a writer before all else, the writing allowing all else, be your guide.

DM: I don’t see the poet as something “special,” but also I don’t see the world of poetry quite in the same way as you describe it, primarily as a critique. For me there is kind of specialness dealing with language with the intensity that the poet comes to. However, all great social thinkers, like Benjamin, have also written a kind of poetry in their work. In other words, you are separating out something that cannot be separated. I do feel that there is something in the activity of writing poetry that could also be in the activity of writing philosophy—a kind of specialness, because for me that activity of working with words means not critiquing but creating the world.

CB: I am just saying that perhaps work within poetics and poetry shares with work within social theory the role of critique, although in other ways they have different functions, different tactics. There are many ways of not going to Rome! Social theory points our certain kinds of things in a different manner, is a different kind of social intervention, than poetry. And poetry has certain aspects of what we really don’t have a better word for than pleasure, which social theory doesn’t necessarily involve. That is, they have functions that are not shared such as the ones you outline. I certainly don’t believe that everything should be the same. There are tables and there are chairs. In the case we’re talking about, the differences are not essence but of use and convention. And these things exist sometimes in harmony and sometimes disharmony, but one is not leading the other on; there is no hierarchical relationship between types of writing.

Postscript by Douglas Messerli

I first met Nina  in Washington, D.C. prior to this interview. I don’t recall the occasion; perhaps she was visiting the University of Maryland, or was introduced to me by professor Milne Holton, who had published several Yugoslavian works of poetry. Or perhaps I was simply introduced to her by some branch of the State Department, who called upon me on regular occasions as a local publisher in D.C., to meet with visiting poets; I do know I met with a couple of poets from the country, as it was named in those days, of Yugoslavia. I also remember attending an event at the Yugoslav embassy, where an elderly poet read what appeared at the time as utterly boring work.

in Washington, D.C. prior to this interview. I don’t recall the occasion; perhaps she was visiting the University of Maryland, or was introduced to me by professor Milne Holton, who had published several Yugoslavian works of poetry. Or perhaps I was simply introduced to her by some branch of the State Department, who called upon me on regular occasions as a local publisher in D.C., to meet with visiting poets; I do know I met with a couple of poets from the country, as it was named in those days, of Yugoslavia. I also remember attending an event at the Yugoslav embassy, where an elderly poet read what appeared at the time as utterly boring work.

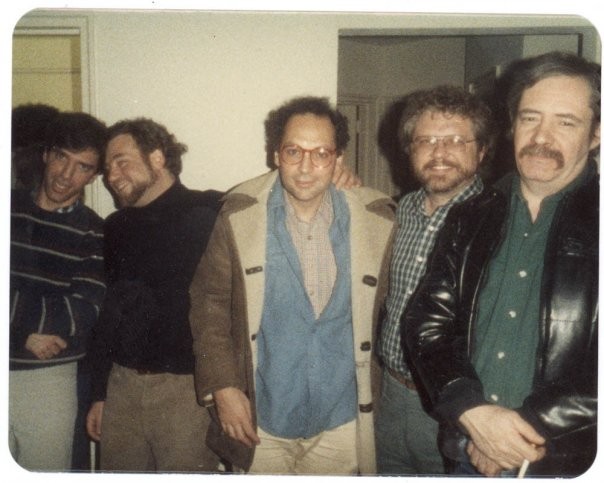

In any event, I immediately liked Nina, and I recall a number of lunches. She had already published books of poetry in Yugoslavia and seemed to me to be rather witty and intelligent. I was delighted when she asked might she interview Charles Bernstein and me, an event which was held, if I remember correctly, in Charles’ and Susan’s then very-small and cramped Amsterdam Avenue apartment in 1983. The piece was eventually published in the University of Maine’s journal Sagetrieb and, later, in a Belgrade poetry magazine, neither of which I now have copies.

Indeed, I’d even forgotten about this interview, until Charles reminded me, sending me a marked-up scan, which I retyped, tweaking, very slightly, a few of my statements, without substantially changing any of the content.

Nina, meanwhile, became romantically involved with Ken Jordan, son of Grove Press and Evergreen Review editor, Fred Jordan. Later, Nina decided to go back to graduate school. I wrote a strong letter for her, and she was accepted into the graduate program at Temple University, where I was then teaching. Although I still believe in Nina’s intelligence and capabilities, it was a disaster on several levels. As my assistant for a freshman English course, she somehow incurred the wrath of many of my students, who felt she had marked up their compositions with far too many red corrections. I checked through dozens of these essays and concurred with Nina’s intelligent comments — to no avail since my students clearly felt that, given her heavy Serbian accent, she was not a competent judge of their English-language efforts. I have no direct knowledge of what she was like as a graduate student, but a couple of my fellow professors also claimed that, in their courses, she was less than stellar, often missing classes. I’ll make no judgments about her classroom abilities, but I can only assume the reactions among my students were based on xenophobia, which I might have suspected of some of my fellow faculty members as well.

Soon after or simultaneously Semiotext(e) published an excellent collection of hers, Inside & Out of Byzantium, and Nina went on to introduce the work of Ginsberg, Kathy Acker, Charles, me and others to Eastern European audiences. Throughout the 1980s she became well known in the downtown New York art and literary worlds.

Ultimately, Nina returned to Europe, marrying a Frenchman, and living in Paris. On one of my several trips to Paris, I dined for lunch with Nina at a wonderful bistro near her apartment, and had a great conversation with her once again. Since then she has published 12 books of poetry, three books of short stories, and two novels. Despite my colleagues’ assessments, accordingly, she is clearly a significant talent.

(Los Angeles, August 21, 2013)