Whose speech? Who speaks?

Vanessa Place's 'Miss Scarlett'

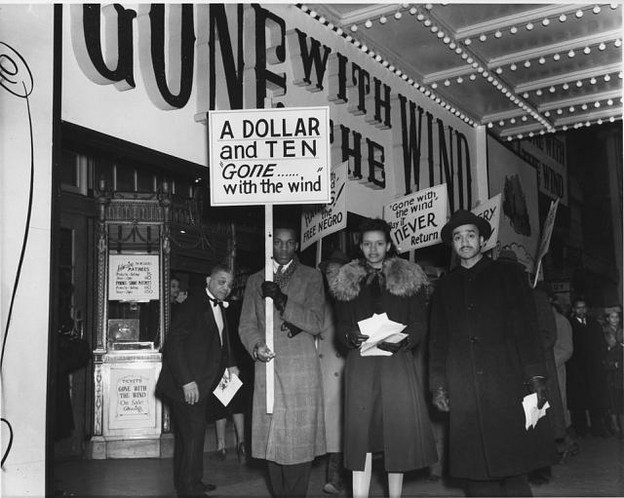

Over on the Poetry Foundation, The Harriet Blog has a write up of my recent post on Vanessa Place’s “White Out” of Gone with the Wind. The Harriet Blog also notes Place’s current retyping of the novel on Twitter, and Brian Reed’s discussion of Place’s “Miss Scarlett” (also an iteration of Gone with the Wind). In a recent talk (which you can watch here), I discussed the relationship between Place’s “White Out” and “Miss Scarlett.” I read “Miss Scarlett” somewhat differently from Reed, as I outline below.

In “Miss Scarlett,” Place appropriates Gone with the Wind in a more overtly discomforting way than in her “White Out”:

Dey’s fightin’ at Jonesboro, Miss Scarlett!

Dey say our gempmums is gittin’ beat.

Oh, Gawd, Miss Scarlett! Whut’ll happen ter

Maw an’ Poke? Oh, Gawd, Miss Scarlett! Whut’ll happen

ter us effen de Yankees gits hyah? Oh,

Gawd—Ah ain’ nebber seed him, Miss Scarlett.

No’m, he ain’ at de horsepittle.

Let’s note (with Brian Reed) that a poem like “Miss Scarlett” is written for our digital world of searchable copies. Because of these digital copies, readers can type a phrase into Google and quickly locate the source text: in this case, all the words spoken the maid Prissy in a section of Gone with the Wind. The passage I’ve just quoted reads in the original:

“Dey’s fightin’ at Jonesboro, Miss Scarlett! Dey say our gempumus is gittin’ beat. Oh, Gawd, Miss Scarlett! Whut’ll happen ter Maw an’ Poke? Oh, Gawd, Miss Scarlett! Whut’ll happen ter us effen de Yankees gits hyah? Oh, Gawd—

Scarlett clapped a hand over the blubbery mouth.

“For God’s sake, hush!”

Yes, what would happen to them if the Yankees came––what would happen to Tara? She pushed the thought firmly back into her mind and grappled with the more pressing emergency. If she thought of these things, she’d begin to scream and bawl like Prissy.

“Where’s Dr. Meade? When’s he coming?”

“Ah ain’ nebber seed him, Miss Scarlett.”

“What!”

“No’m, he ain’ at de horsepittle.”

Place’s rewriting silences Scarlett and the narrator––elsewhere Place deletes sentences like: “‘Some day, I’m going to take a strap to that little wench,’ thought Scarlett savagely, hurrying down the stairs to meet her.” We might, then, again follow Brian Reed and take the poem to show how “Mitchell’s Prissy, notorious as a racist caricature, might have been giving voice to a different and oppositional perspective all along.” Read in this way, Place eliminates and reverses Scarlett’s smothering of Prissy’s speech with her hand. Where Mitchell has Scarlett clap “a hand over the blubbery mouth” of the maid Prissy, Place metaphorically claps a hand over Scarlett’s mouth. This then is a “white out” in another sense––the silencing of the white heroine’s––and, implicitly, the white narrator’s––speech.

But by using only Prissy’s words, Place also increases our focus on her subservience, broken speech, deferral to “Miss Scarlett,” and her fear. Place copies Mitchell’s text, while Miss Scarlett demands that her slave Prissy follow instructions. As a white author, repeating this caricatured imitation of black speech, Place makes these problems of copying doubly uncomfortable. How does one––and should one––give voice to the blackface minstrelsy imitation of African Americans even to attack this caricature? Do I read the passage with my New Zealand vowels or attempt a horribly fake imitation of a horribly fake original? Or should I refuse to repeat it at all? Place pushes the reader and listener into this ethically and emotionally uncomfortable position: she refuses to allow her reader distance.

Iterations