'Their echoes split us'

Sean Bonney rewrites Baudelaire and Rimbaud

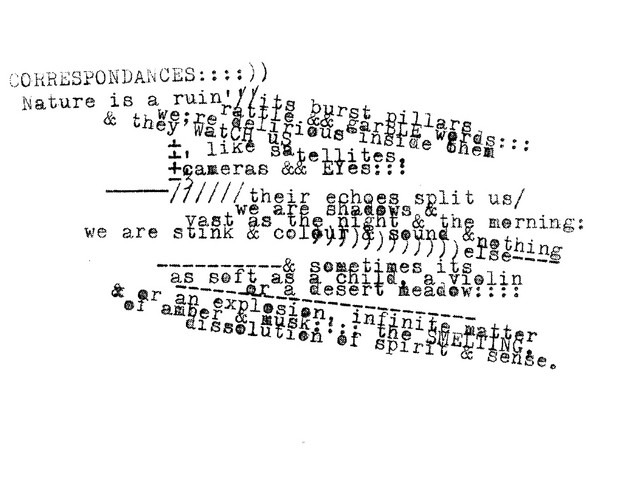

Sean Bonney is another poet who turns to a poetics of iteration as a poetics of revolution. Especially in Baudelaire in English and Happiness: Poems after Rimbaud, Bonney adapts iteration to revolutionary poetic and political ends. In these two books, Bonney attends to the way revolutionary writing, if too direct or smooth, can become implicated in the power structures it seeks to overcome. Bonney’s Baudelaire in English concludes: “the poem is in danger of becoming an overly smooth surface fit only for the lobbies of office buildings and as illustrations / expensive gallery catalogues, that kind of bullshit.” In Baudelaire in English, Bonney stresses the relation between echoes and cracks in the smoothness in his version of “Correspondances,” which contains the phrase “their echoes split us.” Bonney’s texts are idiosyncratic translations of Baudelaire’s poems so breaking the smooth surface of standard translations. Bonney’s translations overlay lines of typewritten text to the point of illegibility, even as they superimpose twenty-first-century London onto nineteenth-century Paris. Through grainy photographs of neglected and forgotten places in London, Bonney (like Baudelaire) emphasizes the ruins and decay of the modern city, the fissure lines and suffering that are the neglected side of the progress of modernity.

In Happiness: Poems after Rimbaud, Bonney again makes the city of London his subject, this time through a focus on the protests against the existing economic and political order that took place in 2010 and 2011 in the wake of the financial crisis. Much of Happiness first appeared on Bonney’s Abandoned Buildingsblog so that the book functions as a retrospective archiving and framing of poems written as news, as part of and in response to a movement for revolutionary change.

Yet for all their immediacy, Bonney’s poems are also presented as iterations––through their positioning “after Rimbaud” and in relation to a revolutionary past. The book begins with an echo, with an epigraph from the Preface to Lissagaray’s History of the Paris Commune: “They who tell the people revolutionary legends, they who amuse themselves with sensational stories, are as criminal as the geographer who would draw up false charts for navigators.” The problem then is how to look back on the revolutionary past without smoothing it over, without transforming it into a nostalgically recalled legend suitable for lobbies of office buildings or expensive catalogues. Bonney stresses and redoubles this problem by echoing past texts (like Lissagaray’s) and events (like the Paris Commune). Lissagaray’s statement opens the entire collection, but Bonney repeats it in the final part of a poem beginning: “We invented colours for the vowels, rich people live there: a mobile holding cell where reality would go on reproducing and representing itself endlessly where we could not exist, a systematic & carefully charted series of political assassinations. Now study this.”

Here, Bonney alludes to Rimbaud’s poem “Voyelles,” or “Vowels,” and to his revolutionary poetics, which, for Bonney, has become smoothed over––has become, like those lobbies and catalogues, a place for “rich people” to live.

Bonney’s repeated echoing of Rimbaud in Happiness contrasts strikingly with Christian Bök’s iterations of Rimbaud’s “Vowels.” Bök turns to Rimbaud to stress not revolutionary politics but linguistic virtuosity. Bök’s most well-known work, Eunoia, takes as its constraint the use of a single vowel in each of its five chapters. Eunoia is in part inspired by Rimbaud’s work: the cover shows each vowel in a stripe of colour that matches the associations between vowel and colour in Rimbaud’s sonnet. Bök has also produced five translations of Rimbaud’s “Voyelles,” each of which is based on constraints involving sounds or letters.

Where in his versions of Rimbaud’s “Vowels” Bök focuses on sounds and graphemes, Bonney is more interested in how Rimbaud’s disruption of grammatical and linguistic certainties relates to an explosion of political, social, and economic structures. But Bonney cautions that the iteration of such a revolutionary poetics might also be entrapping, might just “go on reproducing and representing itself endlessly,” so assassinating the political––as Bonney might read Bök. The poetics of iteration marks both possibilities.

Iterations