Talking with J. Michael Martinez about his new book 'Heredities'

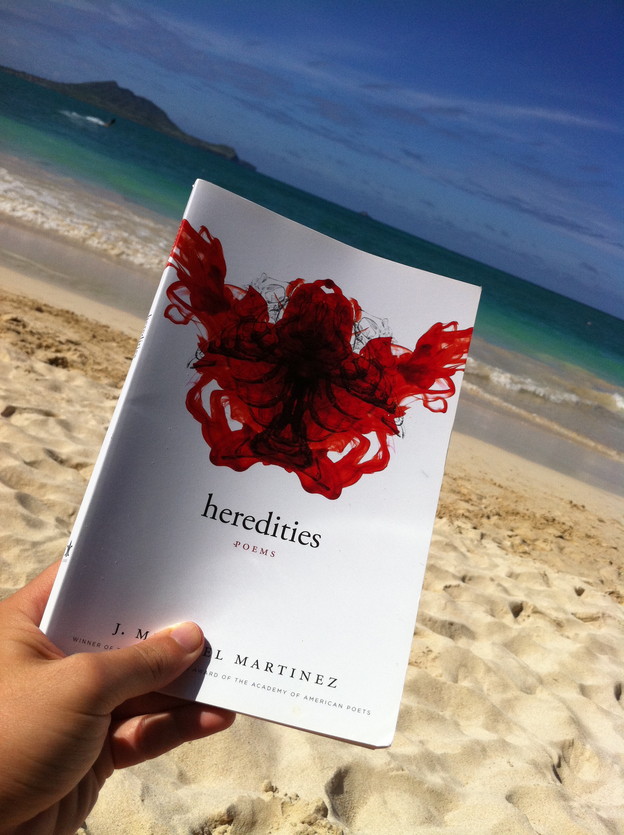

On my beachshelf: Heredities (LSU Press), by J. Michael Martinez, winner of the 2009 Walt Whitman Award. I was so engaged by this book that I had to ask the author a few questions. I hope you enjoy his brilliant responses!

CSP: Heredities is a brilliant title for your collection as it points to both the importance of heredity in your own life, and in the life of many writers of color, but it also speaks to the multiple formations of your identities, languages, and poetics. I also think it's powerful how the title poem continues throughout the book, beginning each section and ending the book. How did you come to this title (or how did it find you)? What made you decide to serialize "Heredities" and use it in each section of the book?

JMM: Craig, first, thanks for taking the time to interview me and I’m looking forward to our dialogue. The collection was initially entitled “Copal” and I already knew that this didn’t represent the work of the manuscript.

I’m an individual who has origin in plural cultural identities and poetic inclinations. I’ve learned, sometimes in very difficult situations, to operate confidently in paradox. You nailed what “Heredities” was intended to encompass: my identities and poetics. I was writing a poem entitled “heredity” in 2006 and my plan was to position it as a proem. However, when I placed it in the manuscript, I saw how the entire book was an attempt to account for my heredities.

As far as poetics, “Heredities” directly alluded to my attachment to plural aesthetic veins: a poetic rooted in the historical literary avant-garde and in an aesthetic that has affinities to Romanticism (one might label it “normative” verse). I tried my hand at a variety of formal conceits in the book and I wanted to bridge these aesthetics that are often, when positioned by certain traditions in the USA, supposedly opposed to each other.

Moreover, I love the lyrical work of the likes of Susan Howe, Rosmarie Waldrop, Michael Palmer and I, in “Heredities, found a way to articulate my sense of my culture through the influence of their work. I loved the intellectual challenge these writers posited and, simply, the music of their line.

In addition, I’ve said this elsewhere, at the time I was writing the work I searched for Chicano writers who were employing formal restraints in the vein of the Language poets and other late 20th century poetics. I couldn’t find any one. This is not to say they weren’t out there, but I didn’t have access to that work. Now, I know Chican@s (as friends and colleagues) that were out there: Roberto Tejada, Gabe Gomez, Carmen Gimenez Smith, et al. When I moved from DC to Boulder, CO, I was introduced to other ethnic writers who were doing this type of work. In fact, this is when I was introduced to your poetry by my friend Rebecca Stoddard.

To answer your last question: I serialized the title to posit the varieties of heredities possible: in language, bodily, in history and in myth/religion. Also, I felt the prose poems grounded some of the more abstract work in a recognizable Chicano tradition, one I love, and a very tangible “voice.”

Yeah, it does seems there's a whole generation of avant-Latin@ writing emerging all over the U.S., inspired by the Language Poets and by innovative poets from "Central" and "South" America. To me, your title seems to also be a subtle reference to the Alfred Arteaga's book Chicano Poetics: Heterotexts and Hybridities. But as you said, the word "heredities" definitely begins to link plural identities and plural aesthetics. Do you feel like avant-Latin@ writing in the U.S. is a passing avant-fad, or is it a lasting paradigm shift?

I read Arteaga’s book as I was working that year on my manuscript; his book is seminal in attempting to trace the then state of Chicano poetics. I’d be proud of any relation with Arteaga.

I’m uncomfortable naming the work of a certain generation of writers as “avant-Latin@” writing. If anything, I think the Chican@s who are pursuing a broader aesthetic in their work have a chance to move beyond the “avant-garde” and its historical framing of literary history. I think these Chican@s/Latin@s participate with the historical avant traditions in that they are performing a type of social critique in their formal strategies. They are doing the critical work in form with an aim to investigate certain politics (of gender, of ethnic identity, of class, of aesthetics). If you look at particular works, like Rosa Alcala’s Undocumentaries or Roberto Tejada’s Mirrors for Gold, you see a questioning of ethnic social markers through aesthetic strategies unprecedented in Chican@ Literature.

I think the “fad” of certain supposed contemporary “avant” forms is in the lack of critical work actually being done. It is easy to employ fragmentation and collage and say it calls into question the signifier and, thus, any conception of stable identity (national, ethnic, or otherwise); moreover, in this destabilization of the lyric voice, it has become too easy to say the poem questions capitalism’s ossification/reification of art, identity, etc. This argument has been around for a century. It itself is reified and has become a literary symbolic commodity. This is to say, in some circles, to not employ these strategies is to face denunciation and to be called a tool of “capitalism” or some other oppressive ideology (the “School of Quietude”). This is to say, to be “in” you gotta wear tight pants and flannel, wear a washed out Marxism, and write your fourth wave Ashbery, Bernstein, or Silliman poem. I quote Charles Altieri at the end of my book to point to this process. He writes, “This heritage of identifications poses challenges because taking oneself as part of the avant-garde tempts writers to dismiss major aspects of their heritage—and, hence, to ignore other, less radical ways of characterizing contemporaneity.” Craig, your essay on the “white avant-garde” points to this.

As opposed to the “white” historical avant-garde’s need to condemn the established/institutionalized forms of poetic enunciation, I think its necessary to honor those forms while pushing outward into a broader aesthetic. I’d like to see a poetics analogous to a philosophical conception of God dating back to the pre-Socratics, that is, as a sphere whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere. I think Chican@s have an opportunity to push formal strategies without dismissing (for the sake of ego-prestige) those forms our elders used, forms our elders fought with to establish our voice in all areas of US citizenship (politically, culturally, aesthetically, etc.). This is another reason I wouldn’t want to say “US Latin@ Avant Garde.” I know I’m not making an oppositional stance toward those lyric forms used by my elders. I know I love, dearly, certain lyrics we call “narrative,” “confessional,” etc. I employ those lyric forms in heredities. What I am against is anyone saying in any absolute way how or what I need to address in order to be a “Chicano” poet (or, simply, a poet). I am against lazy poetry that isn’t doing the critical work necessary to expand consciousness. I’m against lazy minds not wiling to do the work necessary to comprehend that critique.

I also think the visibility today of US Latin@ poets who are employing “innovative” strategies is partly a result of particular parts of the US literary system of production finally getting around to promoting/publishing their work. I mean, Roberto Tejada, Rosa Alcala and Roberto Harrison were writing amazing and critical work in the 90’s (and probably earlier—I know there are other folks who deserve mention, my apologies). Juan Felipe Herrera, Alurista, and other elders were doing “innovative” work before then but they aren’t included in seminal anthologies of “innovative” writing. The fact our work is finally getting visibility has less to do with it being fashionable and more with the rise of visibility of US Latin@s nationally across all fields of cultural production (movies, novels, music). We are getting published, not only because of the quality of the work, but because that work now has material and symbolic (awards) access to contests and publishers willing to publish “the other minority,” i.e. there is an audience willing to consume it. A certain notion of our identity has been institutionalized. The great work and sacrifice of our elders has produced an audience for the 21st century Chican@. The fear I have is letting that work become an exploited/exploiting product like Nike, Wal-Mart or Hollywood (and this has already happened and is happening). I’m scared of this reification. We got to fight this. As Zach de la Rocha of Rage Against The Machine says in “No Shelter”, “…they got you thinking that what you need is what they selling, make you think buyin is rebellin…the thin line between entertainment and war.” This is why I love the work of the Acentos Foundation, the Macondo Foundation, Canto Mundo and individuals/collectives getting out into the community and teaching the youth to own their identities and to own themselves. At the Guadalupe Cultural Center in San Antonio, the poet Vincent Toro is doing amazing work teaching innovative poetry and theater to the youth on the West Side. He is not teaching the “avant” of our poetry, he is showing its all one moment and boundaries only exist in order to be expanded. This is the type of education we got to give our youth: to teach the past and the future as realizable potentials of our present.

In the end, the idea of the “Chican@” is a culturally produced conception, created through literature, movies, food, communities, languages, politics, etc. We as a people got to own how our identity is being produced and remember there is no end product, only constant manifestation.

Moreover, I think its important to keep in mind that the idea of “citizenship” is also a culturally produced illusion with very real political ramifications. And I want to push the limits of these terms (“Chican@,” “US citizenship,” “poetry,” “literature”) in my work and life until they burst.

I don’t think its surprising to see Chican@ poets winning national literary accolades at the same time as certain US States (Arizona, etc.) are legalizing racist laws against us (Eduardo Corral is from Arizona and he just won the Yale Younger Series). This is suppression by racist politicians terrified of the presence, on a national level, of US Latin@s coming to numerical prominence and challenging their economic and cultural hierarchy. The “Chican@,” as a form of mestiza consciousness, is a hybrid, fluid identity encompassing contradictions, an ontology of betweeness (I know we all know this but it needs to be restated). I think this classic idea also needs to be pushed and broadened: I love the idea of the borderland, however, for me, my ethnic subjectivity is more a radical excess exposing the illusion of boundaries than a fragmented, interstitial space. As such, it makes sense politicians are threatened by the rise in the census of the US Latin@, the Chican@: our very identity throws every notion of identity (national, ethnic, racial, economic, etc.) out the window and into a ever expanding social sky. It means that those who are terrified of expanding the idea of US citizenship (Tea Party, most Republocrats, let alone independents) are terrified of revealing to themselves that they are the ones fragmented from wholeness, that they, in legislating and alienating others to maintain their economic and political control, are scared of seeing the endless horizon and individuation we are all capable of.

I mean, in poetics, what would happen if William Carlos Williams’ poetics were recognized as a Latin@ poetic? All the innovations stemming from his influence would have to be recognized as originating with a first generation US Latin@. We are not getting ready to change the map, the map has already been torn down and people are just beginning to realize it.

Chican@s are political and ethnic transvestites. Those Chican@s, visible at the national level, not only represent their ethnic population, but help produce the potential limits of future Chican@s. And we need to keep pushing until all the barriers to being itself are torn down.

The first section of your book focuses on naming--names like "Xicano," "Maria," "Miklo," "Hispanic," and "White". Can you tell us about the significance of naming in your work? In addition, how do you experience the significations of plural namings?

Naming is important to my work because names, the noun, have an ideological tendency to pin-down and act as an illusory absolute. Growing up in Colorado I’ve been called both “white,” “honky,” and “wetback,” “greaser.” Growing up, I got in fistfights with other Chicanos for being too “white.” My brothers and I got in brawls with “whites” for being “brown.” Names are very real to me. How one names oneself, how one names the other is a powerful thing. I am obsessed with names because the act of naming creates a history, a life, a tangible reality for the named person or thing. I got the literal scars on my body from being “named.” These scars are bridges between my different identities and I try to write the scar.

With that in mind, I want to say I don’t identify with the “US Latin@ Avant-garde” or “Chican@ Avant-garde.” I am Chican@. I am a poet. Craig, I like the term you coined in our emails to each other last year: “Ethno-vative.” The Ethno-vative posits communities pursuing a critical poetics resistant to aesthetic, economic and political oppression. And I pray our work, our poetics participates in a paradigm shift in the national consciousness toward a radical openness.

The second section of your book seems to explore the idea of origin(s) and translation. From the poem about Quetzalcoatl ("Binding of the Reeds"), to the long poem "Heredities: Letters of Relation" (which traces text from Cortez's letters during the conquest and Bishop Torquemada's 17th compilation of edicts of the Spanish Inquisition), to the very body of Our Lady of Guadalupe, to a chilling story about your great-great grandparents. Can you tell us a bit about the importance of origins and translations in your work?

When I started writing the work in the second section, I wanted to directly address many of the prototypical Chican@ mythologies. Our Lady of Guadalupe is an image I grew up: I was raised Catholic in Greeley and I attended a little church called Our Lady of Peace. The stained glass windows had various manifestations of the Holy Mother. I remember going to a curandera and, in the “waiting room”, dozens of glass candles with images of Guadalupe burned, plaster castings of the Holy Lady holding baby Jesus. The room was drowned in roses. The curandera would be filled by a spirit and a particular deceased holy man of the last century would speak through her to us. S/he would pray in Spanish to Guadalupe. I was constantly saturated by her myth. The spirit of the last century manifesting in front of my eyes. One of my earliest memories is attending rooms like this. Through my own reading, I fell in love with the mythic sacrifice of Quetzalcoatl.

In a recent conversation with Dr. John Escobedo of CU Boulder, we talked about the post-dated appropriation of the Mexica cultural mythos. Our conversation revolved around the brainstorming if this appropriation was a type of imperialism enacted by Chican@s, if the appropriation perpetuated a historical thinking and trajectory that paralyzed a growth out of linear discourse itself, a narrative whose structure mirrored that of the oppressive ideology we, as Chican@s, were resisting. Simply stated, by creating a historical narrative to situate our identity as “Chican@s,” did we tie ourselves to a historical imaginary necessitating transcendence? At this moment I think so. I could be wrong about this. If not, we end up tying ourselves into a problematic sense of history and time. Our past and future are mythic constructs used to situate a subjectivity that is, I feel, transcendent of time itself.

In the poems of heredities, I wanted to take these emblems of Chican@ identity and reorient them so I could identify myself in them and, simultaneously, out of them. I guess, I think of Walter Benjamin’s dialectical image, a method to redeem time by, not stepping out of it, but by revealing an alternate to that imperial linear discourse of capitalism and coloniality.

Along those lines of thought, what comes up for me at this moment, is the idea to employ those myths Chican@s have appropriated to establish, not a historical trajectory, but a hermeneutic akin to deconstruction or psychoanalysis. We have this with Anzaldua and borderland thinking, with the theoretics of Perez, Mignolo and Baca as Mestiz@ Consciousness. Through this, I see in the mythos themselves another method of analysis: Quetzalcoatl’s sacrifice to redeem time is, to me, a parallel to Walter Benjamin’s dialectical image. Quetzalcoatl’s sacrifice for the sun stands at both the beginning and end of time. It is both within and without human temporal experience. It is the epistemological space of divine abeyance, a silence wherein all potential is both realized and awaiting fulfillment. Quetzalcoatl, as the mythic subject, is the subject and object of his own sacrifice. In the manuscript I am working on now, I’m looking at Ometeotl, the Lord and Lady of Duality. What if Ometeotl could become a figure to articulate gender analysis: masculine and feminine constructs constituted within/without the other. I see this occurring in the recent trend of writing “Latin@” with the “@” symbol at the end: an unpronounceable term composed with the feminine at the center of the masculine. It is not genderless, rather, it is a term in excess of gender; it is unpronounceable, realizable only in the (textual) body.

In the end, I don’t want to look at these myths as history: in this, my sovereignty as an ethnic national subject is surrendered and held as some type of authenticating carrot always seemingly unreachably ahead of me, but truly behind; I end up waltzing in circles, thinking the back is the front. Again, I think of Benjamin, his angel of history. I mean, I want to employ myth, not in mythic recollection in order to establish identity, rather, but as a method toward a non-absolute state of subjectivity, an other-time (by which I mean a temporality where the mythic past is an active organ of the experiencing subject) ceaselessly authenticating “self” outside linear narratives/temporalities and in perpetual individuation (as opposed to individuality, which assumes an “authentic” or “finished” self/subjectivity) in localized communities.

For me, its important to emphasize localized communities. People like to say the “self” or subject is a construct of language and, thus, may be deconstructed into a type of meaninglessness. This troubles me. There is a material reality to our social condition. This reality is rooted in locality. For me, I was born in Colorado to a Chican@ family of migrant farm workers raised in the colonia outside Greeley’s city limits; I’ve experienced racism from a very, very young age. There is a concrete economic system, both monetarily and culturally, oppressing that community. I want to emphasize a radical shift in consciousness that perceives worldly realities without blinders so we, as a community of self-realizing beings, may respond with minute acts of revolution toward larger societal transformations.

This relates to my interest in translation. If language does aide in the cultivation of “identity” or “subjectivity” (in oscillation with material realities) it also aides in the formation of national subjectivities. The archaic Spanish of Torquemada’s marginalia in “Heredities: Letters of Relation” mostly deals with the economics of the Inquisition. I remember reading a book by Earl Shorris and the hypothesis that the Spanish Inquisition’s alienation of the Muslims and Jews aided in the cultivation of the ideology that later gave the colonizers the “moral right” to enact genocide upon the natives of “New Spain.” I wanted, amongst other things, to tie this imperial greed of the Spanish empire (as embodied in the state sanctioned Spanish Inquisition) to my remix/collage of Cortez’s letters. Who controls language (or what gets accessibly published) arbitrates who may claim themselves as national subjects.

In my hometown growing up, I don’t how many times I read in our paper “Opinion” articles from readers calling for the Chican@s of the town to learn English or “to go back to Mexico.” This was nearly always around election time and in response to migrant children coming to school not speaking English. Honestly, fuck that. After a recent reading, I was approached by a woman. She smilingly told me, “You speak English so well!” (ironically, I don’t speak Spanish well, and I don’t have any sign of an accent). She then asked me what part of Latin America I was from (after hearing my bio and poems). How my body and its cultural markers (cheek bones, tan shin, etc.) are perceived connotes to some my language capacities and, in extension, my national identity (hola Arizona).

In relation to our world of poetry, how many poetry journals publish Spanish poetry from US Spanish speakers? German, French, Portuguese etc.? How many guidelines in US literary journals specify “English Only” explicitly or implicitly? Is this truly representative of the US communities generating poetries? I don’t want to appear too critical. I just want to say, with generosity, honor your aesthetic and know its socio-political position, how it positions others.

I wrote a lot here, so I’ll finish this question with this: the poetico-biological analysis of Guadalupe and Quetzalcoatl is related to my personal interest in the body as the site of cultural and national histories. My uncle was exposed to agent orange in Vietnam and he developed a small hole in his spine. His daughter and granddaughter have the exact same spinal fissure in the same location. I have skin ailments that stem from my father’s exposure to agent orange when he served as an MP in Vietnam. Shortly after returning to the US after the war, my dad lost pigment in patches all over his body. His skin is literarily a record of 20th century US imperialism. I’ve biologically inherited a development of this. In this sense, the past is not a concept, it is the living skin, the largest organ of the human body.

Reading the last section of heredities got me thinking not only about parables (as narratives of culture, self, nationalism, history) but also about the forms that these narratives can take. One of the many things I love about your book is that it expresses itself in many forms: single page free verse, multiple page serial poems, prose poems, a visual poem, a poly-columnar poem, a poem with marginalia footnotes, a centered-justified poem, a sideways poem! My eye was never bored. So can you tell us a little bit about how forms emerge and coalesce in your work? What is the relationship between form and content?

I take a long, long time to write a single poem and the formal conceit initiating the poem begins, generally, as an exercise and almost always, formally and conceptually, ends in a radically different form from its beginning.

I never really know what I’m going to write about when I begin. I start an exercise given to me by a friend or, as in the case of “White Song”, from a book I am infatuated with. I allow the language to musically happen and, after I don’t know how many pages, I begin to see a thematic within this generated language. I, then, edit and edit and edit (sometimes for weeks, other times for years). The poly-columnar “Binding of the Reeds” occurred because of the need to construct a form which allowed simultaneous temporal narratives. This was after dwelling on ideas of the messianic and, in messianic temporality, how time occurs on multiple planes: future in the present, past as the future coming towards the present, etc. This speaks to my need, in editing, to address how subjectivity is constructed and how this subjectivity constructs history. I mean, in your books Craig, you form the poems as moments of multiple sequences. I read this formal move as moments in history’s progress manifesting, interruptions of codified histories. One can never be a subject to the whole of history, one, in one’s subjective awareness, perceives history opening from a particular vantage distinct and unique. This subjective vantage is not a fragment, rather, it is what is perceived from the subject in singularity participating in history’s blossoming. This is to say, the form speaks to how history (socio-politically and aesthetically) is ever unfinished: the poem, as an artifact of history and memory, is never completed; we, as the makers of history, are ever generating the past, the future, and our singular presents.

In writing the manuscript I was very conscious of my own need to not be bored. To be less theoretical, when I was a younger I loved The Smashing Pumpkins, Rage Against the Machine, the comic book Kabuki, and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell by William Blake. The Pumpkins wrote the albums “Siamese Dream” and “Melancholy and the Infinite Sadness” with each song musically unique. Rage Against the Machine’s “Battle of Los Angeles”, each song is so musically and lyrically independent from the others on the album. Kabuki’s artist/writer David Mack wrote and painted each single comic in highly individualized ways: each comic book you got different art forms, different narrative structures to articulate the comic’s overarching narrative. William Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell operates in prose, poem, and as a collection of images and aphorisms. It is so radical in its structure. I love this. I was very conscious that I wanted to do something similar in my book. I wanted to emulate a book, a totality, that is a culmination of diverse elements.

One of the things I keep in mind as I edit (after the initial generation of language) is my individual socio-political position in my community. As a Chican@, I can never forget where I am and who I am: this nation and many of its peoples do not allow me the luxury of forgetting my ethnicity. Because of this, I don’t believe in “art for art’s sake.” This idea is one only the politically and economically privileged can claim. One of the things I would like to see banished from US poetries is the idea that any poetry is somehow outside of the political. I mean, sometimes, these claims are rhetorically amusing; however, I would like to see a world of poetries that are willing to make a moral claim and own the responsibilities that comes from this. I believe writers are responsible for their language. I believe you articulate a political and moral position when you write. When people hide behind their aesthetics in order to avoid the difficult conversation of our political realities, it is an act of cowardice. I think poetry operates at the sovereign moment of moral decision. The endless potentials available in the poetic act is a state of freedom that demands critical attention.

Last commentator in paradise