Local crime

Forensic iterations

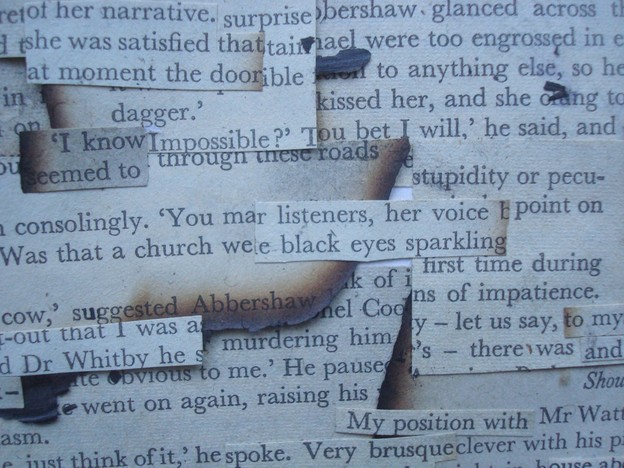

My final post takes a very local turn. Like Prigov’s Little Coffins, New Zealand artist Campbell Walker’s 2012 work The Crime LINKS in the Smoke is an undead work that plays on the print book as both fetishized object and repeatable copy. The Crime comprises cut-up pages from detective novels that were burnt in the fire that destroyed Raven Books, a secondhand bookshop on Princes St in Dunedin, New Zealand. Walker’s book is a memorial both to a particular shop and to the town where it was located. Dunedin, the small city near the southern end of New Zealand where I live, is known for its penguins and sea lions but also for its crumbling Victorian grandeur. Now mainly a university town, Dunedin was once New Zealand’s largest and most prosperous city, and the energetic local cultural scene today springs partly from the spaces opened up by the slow urban decay of a city that never grew. Walker’s work links the fate of Raven Books and Dunedin to the fate of the print codex at a time when bookstores everywhere are closing their doors and e-book sales are increasing exponentially.

By singing Walter Benjamin’s celebration of the codex, Kenneth Goldsmith ironically acknowledged that the book today might just as well mean an e-book or an audiobook, as something made from trees and ink. Walker’s reiterated book seems, by contrast, to stress the material, albeit damaged, paper-based object in the mode of a range of contemporary bookwork art. Indeed, the work becomes hard to read other than as a fetishized object of resistant memory when displayed in the Christchurch Art Gallery (for which it was commissioned as part of The Rose Collection project, led by Christchurch artist Scott Flanagan), in a city whose past has been even more ravaged than Dunedin’s––as a result of a terrifying and tragic earthquake two years ago.

Yet The Crime does not follow so many recent bookwork pieces and treat the book as simply a fetishized object for nostalgia. By splicing together crime fiction novels, Walker also emphasizes the repeatability and interchangeability of the genre and its throwaway lines. Walker has also repeated The Crime by performing the work with sound artist and poet Sally Ann McIntyre. (Both McIntyre and Walker once worked in Raven Books.)

If one takes the various documentary digital images and performance into account, The Crime ceases simply to be a forensic record––a document of personal and local history that bears witness to the loss of a bookshop and to Dunedin’s urban decay. Instead, the work becomes about “burning” in the digital sense––the possibility of further copies and versions that unsettle and overlay notions of materiality tied to the paper page.

Such shifting notions of media––marked in The Crime and in many of the other works of iteration that I have discussed in this commentary––both construct and depend on evolving concepts about what it means to repeat and about the relation of repeating to memory, history, knowledge, and meaning. Digital media, in particular––with their endless permutations of versions, file formats, encodings, hardware, and software––heighten attention to the tenuousness of the copy and its authority, even as they create a world in which we increasingly rely on digital copies in our claims to knowledge. By engaging with this uncertainty, the poetics of iteration provide rich ground for exploring and questioning the modes of copying and burning that we live––and die––by today.

Iterations