Introductory

Toward an Aotearoa poetic?

![]()

A few years ago I wrote a piece entitled Toward an Aotearoa Poetic: a few suggestions about constructing a specifically Aotearoa poetic as opposed to the — then extant — mono-cultural, monolingual, monocentric monotonous model of what poetry is and means to many Kiwis.

Down the track of time somewhat and now living right back bang in the centre of this skinny country, my essential points still remain valid, given that my many generalizations in that piece remain exactly that: the piece requires modification and further reflection. It was never meant to be an ‘academic’ item either.

More recently, I do wonder if there ever could be such an all-encompassing poetic across the wide strand of poetry scenes & scenarios thriving both through the midriff and along the lengthy limbs of Aotearoa — poetry slams, for example, are de rigeur here nowadays. Are there just too many discourses, audiences, markets, methods of publication, venues, and ‘schools’ here, given that there is never ever sufficient funding for any of them anyway?

I will — in ensuing Commentaries — attempt to size up these several scenes, so to speak, more specifically, given however that nothing is that clear-cut. Take, for example, Kiri Piahana-Wong — she is not only a Kiwi-Asian poet, but also, of course, a Kiwi-Māori poet. More, she is the fulcrum of Anahera Press, a vibrant and viable small press. Doug Poole is a Kiwi-Samoan poet, runs the fine online poetry machine Blackmail Press, as well as is the kaiwhakahaere (boss) of the Poetry Slam at the thriving Going West Writers Festival every year. Nothing is black and white in Aotearoa poetry, given that white still dominates here.

More, nothing is without tangents toward something else within this, the New Zealand poetry spectrum — as we shall see — which has a great deal to do with the small size of the population. It’s six steps from Kevin, sorry Kiwi, Bacon all over again.

What were my points anyway?

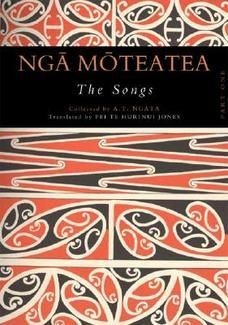

Jack Ross has, of course, enabled a series of earlier commentaries in Jacket 2 (during 2012), where he reflected about ‘my ongoing engagement with New Zealand poetry.’ Yet, Jack, for all his ensuing comments, never touched on the first New Zealand poetry that had existed on the shores of this country for hundreds of years before any English language versifiers ever entered the scene. This, of course is ngā mōteatea Māori, which necessarily must be included as a vital and ongoing component of Aotearoa poetics. ‘Maori language and Māori oral literature may come to be seen as being … crucial to the development of New Zealand literature … an acquaintance with Māori language and literature is a necessary prerequisite for making Olympian judgments about the nature of New Zealand literature as a whole’ wrote the late Michael King back in 1993. Yet, for a very long time — unfortunately – New Zealanders completely ignored — or worse — abnegated Maori as Being. Take Charles Brasch in his The Silent Land (1945) with its wails that ‘The mountains are empty / The plains are nameless’. It took Peter Beatson, (1989), to write back, ‘The alarming thing about (Brasch’s) poem’s total amnesia towards a thousand years of Māori union with Aotearoa is that it was shared by many New Zealanders up until the mid-sixties, and I suspect it is still prevalent today.’

I will quote now selectively from my Landfall (2012) article entitledNgā Mōteatea: traditional Māori language poetryabout theexistential importance of ngā mōteatea to Māori and therefore to us all —

Māori iwi (tribes) always had poetry. It performed a major role in defining individuals in relation to their iwi, to their whenua (land), to each other. It defined them and their ao or world. It was them – it still is.‘There is no better qualification than a knowledge of the songs. In them are embedded expressions which are applicable to each and every circumstance concerning the Māori’ (Sir Apirana Ngata and Pei Te Hurinui Jones, 1961.)

The history is massive and long and vital. Māori poetry was an umbilical cord to tipuna(ancestors), beginnings, to thousands of years of iwi history. ‘Such chants are very ancient and are to a certain extent regarded as sacred, embodying esoteric knowledge and embalming memories of far-off Hawaikian ancestors, when mankind was near akin to the gods.’(James Cowan, 1987.)

Māori poetry was – and remains today — an oral form, as best summed up by a well-known whakataukīor proverb, Ko ta te rangatira, ko tāna kai he kōrero (‘As for the chief, his food is speech.’) A respected expert on Māori literature, Te Kapunga Matemoana ‘Koro’ Dewes was at pains to emphasize this: ‘Oral proficiency in Maori should be the basic aim and should permeate all language and literature courses, because the bulk of our literature (history and music) is oral’ (1975.)[And I well remember Koro for we were Te Araroa residents together!]

Because all traditional Māori poetry was written in te reo Māori and can never be transliterated adequately into any other tongue, it is difficult for non-Māori speakers to appreciate the sheer beauty of the language use in these paeans.

It is the brilliant Ngata-Jones-Mead anthologies of Māori poetry that are the paramount definitive model, or lodestone, for Māori mōteatea — and now available in four sets, some with accompanying CDs. Ngata began his collecting in the 1920s and the first two volumes — written only in te reo Māori — were initially published eighty years ago. He and Jones never entirely finished their monumental work. Bruce Biggs, writing about these Ngata and co. anthologies of ‘Māori poetry as compiled by Māori’, stated, ‘This is the only useful classification of a body of Polynesian poetry known to me. Its success is due to the complete break-away from traditional literary categories’[my stress].Unlike the straight-ahead timeline patterning and neat subject-grouping of European classification systems, Māori poetry is characterized by ‘situational, episodic, variant oral narratives’ (Jane McRae, 2000). The intent of the original makers of Māori poems were other; they did not share the ‘linear chronology and encyclopedic intent’(ibid.) of European scribes.

Aotearoa-New Zealand poetry has, then, a mighty non-English language tradition and — despite the ignorance and denigration of several Pākehā (European) critics over the years — sadly, none less so than our current Poet Laureate — this continues to thrive today, as Charles Royal (2009) points out —

‘… numerous new songs have been composed, particularly in the context of Māori performing arts competitions. A new impetus and energy is emerging concerning the composition of new songs based on a thorough grounding on mōteatea of the past.’

Indeed, below is a link to modern mōteatea Māori by a good friend of mine, Iraia Bailey, a fellow Hong Kong Kiwi expatriate, as first published in the Maori and Indigenous Review Journal (2011), of which I was the original poetry editor.

So, there is a very powerful Māori poetic extant here, a poetic, that although ontologically distinct in terms of its genesis, continues to carry immense weight via the manifold Māori kapa haka and waiata festivals nationwide and daily on ngā marae, but even more so, due to its influence on some (not all) Māori poets writing in some form of English today, for- and here I quote from the same Landfall piece -

… although ngā mōteatea Māori were a separate and different art form to ‘traditional’ English-language poetry, elements of these ngā mōteatea Māori are often nowadays incorporated by more recent Māori poets writing in English …. Indeed many poems in/partly in English submitted to the MAI Review Journal display some of these specifically Māori features, whereby the piece is to be sung or chanted, where the rhythm means more than rhyme, where repetition plays a major role in the delivery, where the deliberate metre dawns on delivery.Or as Keri Hulme (1991) noted several years ago about her contemporaneous Māori poets writing in English: ‘They owe much to Māori thought and mythology and ways of expression.’

Ngā mōteatea Māori never died away, remain influential and are vital.

Now, in later Commentaries I will look more closely at Māori writing in English and reasons as to why they do so.

Another very important population dynamic that needs to be incorporated into any Commentary on poetry and poetics in this increasingly multicultural country, is the incredible growth of Pasifika, and even more markedly, Asian peoples, with a concomitant and inevitable focus on poets from these areas, not all of whom either will or can or want to write in the English language. Let’s look at this demographic —

Figure One: Projected Population 2013-2038 — Census New Zealand 2013:

National ethnic population projections indicate New Zealand's future population for four broad and overlapping ethnic groups.

The projections indicate a 90 percent chance that New Zealand's:

- 'European or Other' population (3.31 million in 2013) will increase to 3.43–3.62 million in 2025 and to 3.43–3.82 million in 2038.

- Māori population (0.69 million in 2013) will increase to 0.83–0.91 million in 2025 and to 1.00–1.18 million in 2038.

- Asian population (0.54 million in 2013) will increase to 0.81–0.92 million in 2025 and to 1.06–1.26 million in 2038.

- Pacific population (0.34 million in 2013) will increase to 0.44–0.48 million in 2025 and to 0.54–0.65 million in 2038.

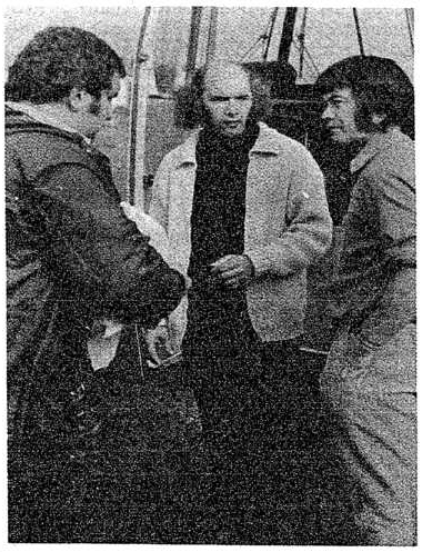

Selwyn Muru, Para Matchitt, Malta Sydney - at the first ever Maaori Artists's hui, Te Kaha in 1973. Selwyn is still going strong and was at the launch of the compilation of the Maaori poetry book Puna Wai Korero late in 2014. Selwyn actually had run the radio programme with the same name back in 1971.

Therefore the New Zealand population mix is undergoing a rapid sea change and any poetic must reflect this. The Asian and Pasifika voices are burgeoning — which I also will comment on later in our spin down the verse highway. This time around, Jack Ross is right on’, that there is a need now to escape English — ‘… but New Zealand poets (and publishers) have to work a bit harder to jolt themselves out of their “English-is-the-one-world-language” rut, I feel … It’s simply not true to the reality of modern New Zealand for our writers to imply that we only speak and understand one language here.’

All of which leads me to go back to my original attempt to draw up an Aotearoa poetic. For, yes, it is English-language, Pākehā dominated (university) presses and literary magazines, which still rule and gate-keep here: poems are written in English and poets tend to continue to write stylistically ‘close to England’. By which I mean that they are — generally — not writing against England-derived poetic parameters in any way, shape, form or — often, also — theme. Of course there are exceptions to my general point here — AUP published the fine Ngata-Jones edition of Ngā Mōteatea as just one example, while Penguin bravely included mōteatea in their ground-breaking Book of New Zealand Verse back in 1985. However even if they do publish Māori and Pasifika and some Asian poets, these latter tend to be writing almost entirely in the English language.

For Māori this is definitely because the rampant colonization and suppression of te reo Māori meant that many had lost their language some generations ago. I am very aware that many Māori poets who are published in New Zealand today don’t have the reo (language), eh. Besides which, the journals and publishers hold fast to English language like a baby grasps his rattle: they all too often will publish only in that lingo. I write a lot of poetry in te reo Māori, but ironically I am published more overseas in my own tongue than I am here in Aotearoa - The Capilano Review (2015)and Antipodes (2014) are two journals who have published me recently in Māori.

I also reflect on Stephen Greenblatt’s 1990 comments about how the dominant discourse always seems to ‘co-opt, assimilate and neutralize any subversive voices’ i.e. the Centre survives, while the small presses and poetry sites on the margins tend to eventually fall away, all too often subsumed by the avaricious English language monster.

To summarize thus far. There are several poetry beasts chewing up the grass in this country and they all too often do not graze happily in the same paddocks. As the astute Hirini Melbourne wrote in 1991 ‘This is why it is so difficult to define a distinctive Māori ‘literature’: the distance between Māori oral and written forms and Western understandings of literature is simply too great.' It’s just that the bloody paddocks are chewed up far too much by English-speaking tongues.

It is here also that I refer readers to English Language as Hydra (Multilingual Matters, UK. 2012) — which I instigated and co-edited. And which is a strong critique of just how agencies of English language promotion and subsequent dominion deleteriously affected and continue to affect Indigenous cultures, languages, weltanschauung. I asked both Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o and Muhammad Haji Salleh to contribute the Preface and Afterword to this important book and they were happy to oblige — and to stress just how much the inherent tropes of English language had affected them, to the extent of their now writing in their own indigenous tongues as much as possible. Sort of makes CK Stead’s comments from 1990 (Times Literary Supplement) particularly worrying — ‘The time has come for those who are seriously committed to a New Zealand literature to reaffirm our British and European inheritance, and our consequent kinship to the English language …’ Amazingly benighted thinking from a great poet and one of my own excellent university lecturers from last century.

Instead I ask you to consider these lines — by the fine Māori poet, JC Sturm (aka Jacquie Papuni) —

Pākehā you

Milton directing your head

Donne pumping your heart

You singing

Some English folksong

JC Sturm

Similarly, it will be fascinating also to look in these Commentaries at poets and ‘zines and events, which are getting away from (old style) English language dominion/gatekeeping and are heading toward a multilingual ambience, which includes deliberate code-switching (see the work of Powhiri Wharemarama Rika-Heke in this regard), and also alternative styles, formats, typographies and visual effects. As well as wider range of (existential) themes than is generally foist upon the New Zealand reading public.

For as Joan Fleming wrote very recently in Cordite in respect of the editors of the new kid on the online poetry block, Sweet Mammalian - they are, 'tired of the cool, collected, observational and analytic mode that runs through so much poetry.' That’s been my own attitude for the last 45 years too, as I warbled on in that Toward an Aotearoa Poetic piece about Existential Literary Criticism, namely that ‘Obviously I am calling for more guts in a poem — not merely despair and anger, but joy, fun, humour — although not so overly overt as to seep into sheer sentimentality’ It would be great to see poets in this country touch more on the passionate themes of great Māori wahine (women) poets like Hinewirangi Kohu-Morgan and the late Bub Bridger, eh.

So the following Commentaries will reflect all this variegation and focus on the Other, more than the familiar Pākehā, middle-class stand-accused-again Centre (à la The Empire Writes Back from 1989.) All the time being cognizant that any Aotearoa poetic must reflect ALL the peoples in this multicultural land, and indeed beyond. This is, of course, not to ignore the Centre either, as we shall also carry commentary on this crux – and stop talking about me so much, eh!.

For Aotearoa-New Zealand is not a Britain in the South Seas (from James Belich, 2001) — and never was, despite the best intentions of the agents of England from prior to 1840 onwards. It never will be, it never can be. Let’s write and publish our poetry accordingly.

![]()

LINKS:

Ngā whakaaro