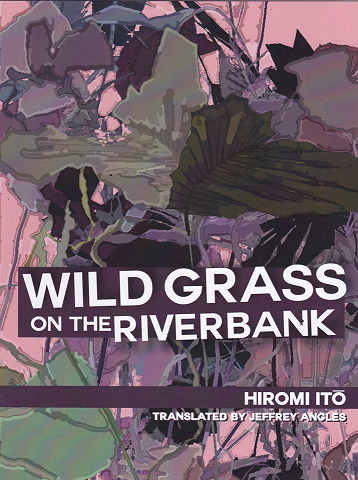

Hiromi Itō: From 'Wild Grass on the Riverbank' (just published)

Translation from Japanese by Jeffrey Angles

[Two years after the first publication of the following extract in Poems and Poetics, Hiromi Itō’s Wild Grass on the Riverbank has now been published by Action Books in a definitive English translation by Jeffrey Angles. One of the most important poets of contemporary Japan, her impact has been summarized by fellow poet Kido Shuri as follows: “The appearance of Itō Hiromi, a figure that one might best call a ‘shamaness of poetry’ (shi no miko) was an enormous event in post-postwar poetry. Her physiological sensitivity and writing style, which cannot be captured within any existing framework, became the igniting force behind the subsequent flourishing of ‘women’s poetry’ (josei shi), just as Hagiwara Sakutarō had revolutionized modern poetry with his morbid sensitivity and colloquial style.” More on Itō and this important new work follows the excerpt from the work itself. (J.R.)]

Michiyuki

By late summer, everyone on the riverbank was dead,

Not just the once living creatures, but the summer grass, the rusted bicycles, the summer grass,

Cars without doors or windows, the warped porn magazines, the summer grass,

Empty cans with food stuck inside and empty bottles full of muddy water,

Girl’s panties and condoms, the dead body of father, and so much summer grass

The riverbank meant only to control you

The summer grass touched our bodies

The seeds falling down onto our bodies

Recently, on the bank, I noticed a kind of grass that multiplied conspicuously

It is about one meter high and stands like some kind of rice

It has ears

It is everywhere

It glimmers white in the dim evening light

Sticky liquid oozes from the ear

The dogs get sticky

The dogs smell terrible

The dogs agonize and rub their bodies onto the ground

The man from the riverbank appears in the evening

Every evening he appears, sits in an arbor

Completely alone

Aged, unpolished and shabby, pale as a corpse

When his penis rises up

A smell rises like the one from the rice-like grass on the bank

The penis in his hands shines and shines

The flowers of the kudzu also rise up, I notice the arrowroot flowers rising up here and there, one day, we became tangled in the tendrils of the kudzu plants, I heard something slithering along abruptly, no sooner had I heard this when a tendril trapped my heel, it hit me, and knocked me on my back into a bush, there the Sorghum halepense rattled in the wind, an unfamiliar grass shook releasing its scent, then the tendril stretched all the further, crawling onto my body, getting into my panties, and creeping into my vagina, I… I inhaled and exhaled, I exhaled and the tendril slid in, I inhaled and the tendril slid out, I exhaled again and it slid further in, like the leaves of the kudzu my body was turned this way and that, my body was forced open and closed over and over, and Alexsa watched all of this, Alexsa was watching, watching and smiling, I became angry, so angry, I got up and shoved Alexsa away, she fell down on her back, the tendrils clung to Alexsa too, Alexsa also turned this way and that, the tendril also went inside her vagina, deep inside, and she started to cry

Everyone was dead

Father

Brother

Mother and me

Ahh…I think to myself

Think I'll pack it in

And buy a pick-up

Take it down to L.A.

Find a place

To call my own

Or maybe a hot sprint

One that heals eczema, dermatitis, neuralgia

Menopausal disorders, diabetes, infectious diseases

A hot spring in a hot sprint to fix you up right away

To soak yourself, open your pores, scrub your body, swell up

And then start a brand new day

Hey I’m itchy, so itchy, my younger brother cried, I told him not to scratch, but he did it anyway, the place he scratched soon turned into a blister, I didn’t scratch it that much, only a little, brother cried, but even if he only scratched a little, the place he scratched turned into a blister, all over his body were blisters, after they ruptured, they got inflamed and full of pus

My little brother no longer seemed like himself, he was horribly swollen, he rolled all over the house, mouth open, wheezing, crying,

Crying,

I want to take him to a hot spring, Mother said I’ve heard of a hot spring good for your skin, if we’re going, why don’t we take our dead father and dead dog along to put in, so just left everything as it was, dirty dishes, old clothes, wet towels just as they were, then we carefully laid my wheezing brother on the rear seat, and we stuffed some other things in the car, my little sister, spare clothes, dead bodies, dogs, plastic bags, pillows, food and drink (even some flowerpots), so much stuff, and then we took off, as I stared at the road from the passenger seat, I asked, how do we get there? Mother replied as she drove the car, it’s over that mountain

That hot spring is

A hot spring that fixes you up right away

Soak yourself, open your pores, scrub your body, swell up

And fix your eczema, blisters

Skin infections, ringworm

Dermatitis, infectious diseases

Atopy, allergic diseases

Dead bodies, death, dying, and having died

Try to fix you up and

And start a brand new day

Anyway

Let’s go over that mountain, Mother said

The back seat was full, no space left

As for space, the car was old and rickety from the start

But still we stuffed it full with

Things, garbage, food

People, dogs, dead bodies

So there was no space

The dogs stunk

The dead bodies stunk

My brother was wheezing in the back seat

My sister sometimes cried out as if she’d just remembered

She’d left something back at home

Please go back, I forgot something

No, we never go back

We just go further

Beyond that forked road

Isn’t that Toroku?

Isn’t that Kurokami?

Isn’t that Kokai?

The Jyogyoji crossing

Through Uchi-tsuboi

Up Setozaka slope

Shouldn’t we go

All the way over there?

I know the way to the big tree

Where the samurai-turned-monk used to live

At his big tree, we turn right at the three-way intersection

We see the huge treetop of his big tree

From here, it looks so huge

If you go under and look up, it blocks out the whole world

There’s a path only for tractors and pick-ups

Turn right at the three-way intersection

There’s a small stone bridge, we cross it

Then another three-way intersection

Go straight

Go straight

Go up the road

Go through mandarin orange orchards on both sides

And when we come out

We come to mountainous roads

Where it’s dark even during the day

The road meanders through a forest with shining leaves

The road meanders

Comes close to a cliff

Then separates from it

Ahh… I think to myself

Think I'll pack it in, and buy a pick-up, take it down to L.A.

Mother started to sing in a key way too high for her

Ahh… Think I’ll…

A tangle of karasuuri flowers and fruits

Ahh, Think I’ll…

A flourishing bunch of worm-eaten leaves

A scarlet flower is blooming

It must be a garden species that escaped somebody’s terrace

In the shade of the plants, a large white flower is blooming

A flower pale and white

That can’t be a garden species

It’s so pale because it’s in the shade

Another car comes

We pass each other

That car must be coming back from the hot spring

All fixed up, the driver must have fixed his skin trouble

And come back, thinking this, I try to get a good look

But it disappeared into the distance in a flash

Much further and we’ll be at the seashore

The seashore facing west

Doesn’t look like there is a hot spring

Beyond this is the pure land, Mother said

The dog noticed the smell of the sea

It stuck its nose out the window, howling for the sea

We should’ve crossed a large bridge, Mother said

I forgot the name, but it’s a large bridge

There were big floods there late in the nineteenth century

And again in the mid-twentieth century

Lots of earth, sand, and drowned bodies caught on the bridge

‘Cause of that bridge, the floods downstream were even worse

We screwed up when we missed that bridge

All the water we’ve seen has just been small streams

We’ve definitely gone the wrong way, Mother said

We’ll never get there if we keep going like this, Mother said

The dog howling for the sea rose up in the rear seat

And walked across my little brother

Alexsa shouted

We’d better start all over, Mother said

She must have given up

My brother let up a sharp cry

You can’t give up

Is that the only option?

Shut up, Alexsa shouted

I told you, I told you, my little sister wept

The dog barked

Lots of dogs barked

Alexsa shouted, I can’t take it anymore, I can’t, I can’t

No one ever listens to me, she said

She sunk her face into her thighs, curled up, started to sob

Her voice grew louder, more childish than brother’s

More infantile than sister’s

Cried on and on, on and on

Nothing else

On and on

On and on

We should have turned around

But if we did, we’d just get more lost, mother said

Let’s keep going down the hill to the sea

Then go home round the cape

So that’s how we got back home

Nothing fixed

Nothing found

Nothing

We failed

It’s no good

It’s all over

NOTE. The 140-page narrative poem Wild Grass on the Riverbank (Kawara arekusa) represents Hiromi Itō’s dramatic return to poetry after several years of writing primarily prose works. First serialized in the prominent Japanese poetry journal Handbook of Modern Poetry (Gendai shi techō) in 2004 and 2005, Wild Grass was published in book form in 2005. ... The critic Tochigi Nobuaki has said that in Wild Grass, “We, Ito's readers, are witnessing the advent of a new poetic language that modern Japanese has never seen.” Wild Grass explores the experience of migrancy and alienation through the eyes of an eleven-year old girl who narrates the long poem. In the work, the girl travels with her mother back and forth between a dry landscape known in the poem as the “wasteland,” a place that resembles the dry landscape of southwestern California [where Itō now lives], and a lush, overgrown place known as the “riverbank,” which resembles Kumamoto, a city in southern Japan where Itō’s children grew up and where Itō still spends several weeks each year.

NOTE ON THE SUBTITLE: Michiyuki are lyric compositions that feature prominently in bunraku and kabuki dramas of the early modern era. Typically, they describe the scenery that characters encounter while traveling—sometimes while eloping or traveling to a site where they will commit suicide. For this reason, michiyuki typically come at the climactic moment of a drama. In Itō’s poem, however, the michiyuki sequence is profoundly anticlimactic as the characters travel and travel in search of a place they cannot find. This chapter contains quotes and passages loosely based upon the lyrics of Neil Young’s song “Harvest” from 1972.

Poems and poetics