Burning Deck Postcards

A detour in forgetting

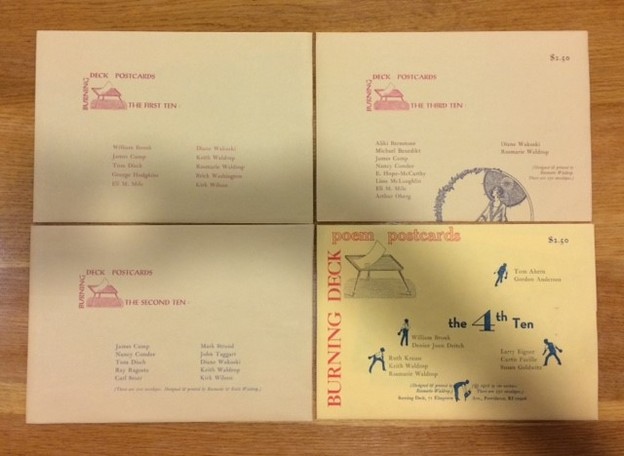

I’ve been thinking for a while on what to write about Burning Deck’s Postcards, published in a series of four sets from 1974–1978, which are part of The Little Magazine in America Collection at DU Libraries.

Where, exactly, does one start when addressing a small piece among nearly sixty years of Burning Deck publications, of Burning Deck publishers Keith and Rosmarie Waldrop’s presence in American poetry? To briefly revisit the last couple posts in this Commentary series, I’ll point out that Burning Deck published Pam Rehm’s The Garment in Which No One Had Slept in 1993, as well as Barbara Guest’s The Countess from Minneapolis in 1976 and her Biography in 1980. And Keith and Rosmarie Waldrop were contributing editors for apex of the M.

It’s taken me a road trip from Denver, Colorado to Seaview, Washington to formulate my thoughts, and it’s worth noting that in Portland, Oregon, on my way to Seaview, I picked up the Waldrops’ gorgeous Keeping / the window open: Interviews, statements, alarms, excursions, edited by Ben Lerner and published by Wave Books a handful of months ago in May. In reading through Keeping / the window open I was drawn to something Rosmarie wrote in December 1997 for Ceci n’est pas Keith / Ceci n’est pas Rosmarie, published by Burning Deck in 2002. In a section titled “COLLAGE, THE SPLICE OF LIFE,” she wrote, “Whether we are conscious of it or not, we always write on top of a palimpsest.”[1]

At its core, “palimpsest” derives from the Ancient Greek palímpsēstos, meaning “again scraped.” In one Oxford English Dictionary definition of palimpsest, the phrase “multilayered record” appears: “In extended use: a thing likened to such a writing surface, esp. in having been reused or altered while still retaining traces of its earlier form; a multilayered record.” For me, the phrase calls up memory, music, painting, color, photographs, warmth (think layers of clothing, layers of blankets), soil, stratum, and, of course, words. What gives us life and meaning, surrounds us, and keeps us.

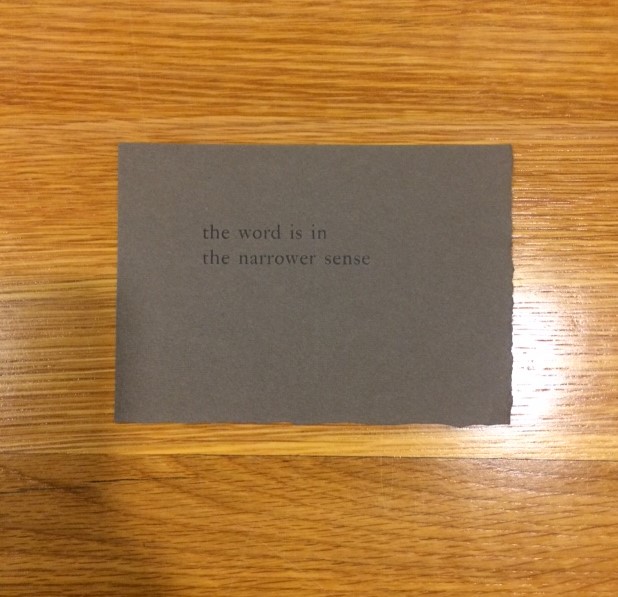

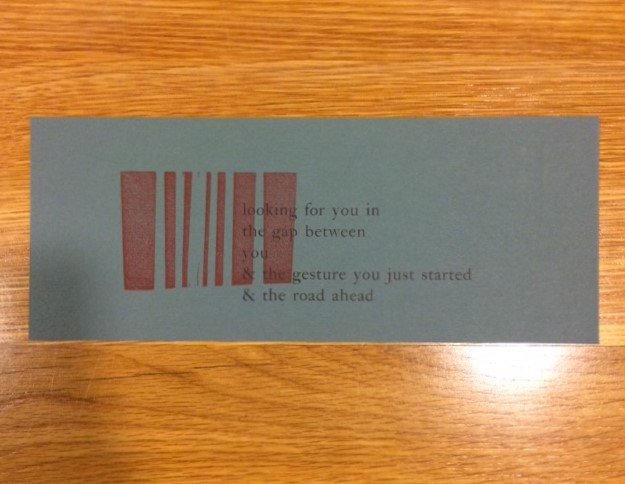

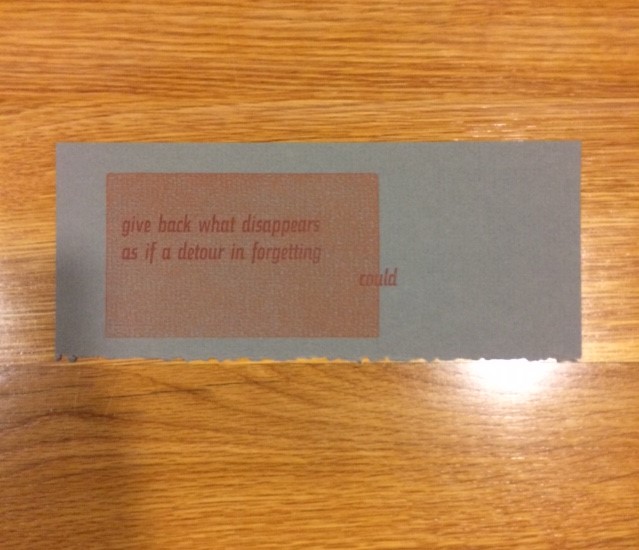

It happens that Rosmarie’s postcards, which appear in The First Ten (1974), The Second Ten (1975), and the 4th ten (1978) of the Burning Deck Postcards are all some kind of gray — a brown gray in the The First Ten, a slate gray The Second Ten, a slightly lavender gray in the 4th ten. I adore gray, and the color’s often given short shrift. Gray is difficult and uncertain and between. Why bother. On the other hand, Henri Cartier-Bresson once said to William Eggleston, “You know, William, color is bullshit.”[2]

Take a look at Rosmarie’s postcards below. Left to right: “the word is in / the narrower sense” from The First Ten; “looking for you in / the gap between / you / & the gesture you just started / & the road ahead” from The Third Ten; and “give back what disappears / as if a detour in forgetting // could” from the 4th ten.

How are Rosmarie’s postcards, or any of the Burning Deck Postcards, not multilayered records? Letters, words, color, ink, shapes, paper, fiber, space. Rosmarie’s poem from the 4th ten went on to become part of Nothing Has Changed (click on the link to read the poem in full), published in 1981 by Brita Bergland’s Awede Press. The postcard from the 4th ten is, after several sessions of looking through Burning Deck Postcards, the one I can’t forget. I’m a sucker for absence, though, so it figures that I’d be drawn to a figure comprised of eleven words that work beautifully to, for a brief window of time, bring back what was. (There’s again scraping.) Also, the shape that contains most of the poem’s text resembles a couple states I’ve lived in, states that neighbor one another: Colorado and Wyoming. The could that occupies the eastern side of the shape in Rosmarie’s poem could be located on the Colorado-Kansas state line, the Wyoming-Nebraska state line. That could does the work of resignation and hope, yes and no, presence and absence.

When I was a young reader, The Jolly Postman or Other People’s Letters, published in 1986 by Janet and Allan Ahlberg, brought me great joy. The book is written in narrative verse and follows a carrier along his daily route delivering mail to British fairy tale characters. The story incorporates envelopes in which one might find a letter, a game, a puzzle, a card. Also, clearly, there’s an element of illegality baked into the whole scheme. The joy lies in the ritual of surprise and uncertainty that accompanies unexpected mail, and on the flipside there’s the anticipation and certainty that accompanies good mail’s arrival. That you’re receiving something — communication, a gift, a feeling to which you can respond in reciprocity if you wish — is immense. When I spend time with the Burning Deck Postcards, I can’t help but think of all this, think fondly of a book that I routinely revisited when I was a kind of sponge in the world, and think of the generosity inherent in everything we’ve been given by Keith and Rosmarie Waldrop.

In the Burning Deck Postcards, one finds poems by William Bronk, Larry Eigner, John Taggart, Diane Wakoski, and, of course, Rosmarie and Keith Waldrop (to name only a few). The Bronk poem in The First Ten, “The Fragile Endurance of the World,” is printed on a paper stock that’s fluorescent yellow. Elsewhere, there’s hot pink, mustard, orange, stark white, maroon, eggplant, speckled black, polka dots, plaid, and a puddle of engine coolant green on a cream-colored paper stock to accompany a Wakoski poem that features pissing. In his introduction to Keeping / the window open the poet Aaron Kunin writes of meaningful instructions he’s gleaned from Keith and Rosmarie, and one of those instructions is You don’t have to decide whether you’re going to be serious or unserious.[3]

Discussing the meaning of “between” in an interview with the poet Christine Hume in 12 x 12: Conversations in 21st Century Poetry and Poetics, Rosmarie says, “I think of the “between” more in terms of … extending the gray zone between the black/white in the direction of multivalence. ‘The yes and no in everything.’”[4]

1. Keith and Rosmarie Waldrop, Keeping / the window open: Interviews, statements, alarms, excursions, ed. Ben Lerner (Seattle: Wave Books, 2019), 62.

2. Augusten Burroughs, “William Eggleston, the Pioneer of Color Photography,” The New York Times Style Magazine, October 16, 2016.

3. Keith and Rosmarie Waldrop, Keeping / the window open: Interviews, statements, alarms, excursions, ed. Ben Lerner (Seattle: Wave Books, 2019), xii.

4. Christine Hume and Rosmarie Waldrop, “Christine Hume and Rosmarie Waldrop in Conversation,” 12 x 12: Conversations in 21st Century Poetry and Poetics, ed. Christina Mengert, Joshua Marie Wilkinson (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2010), 79.

The Little Magazine in America Collection at University of Denver Libraries