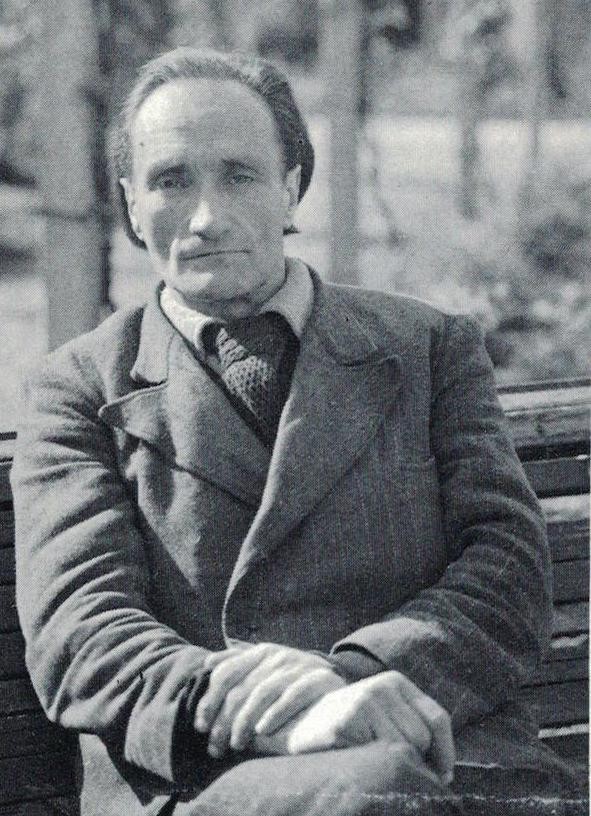

Antonin Artaud: The asylums and after

On his way back from Ireland in 1937, Artaud was put into a straight jacket. Once back on French soil, he was turned over to the authorities. This was the beginning of a nine-year stint in hospitals with Artaud in what biographer Martin Esslin called a “near-catatonic state.” Artaud has been hailed as one of the strongest influences on the theater in the 20th century, and The Theater and Its Double is his seminal work. This masterpiece, published in 1938 while he was detained, is where Artaud says, “If Shakespeare and his imitators have gradually insinuated the idea of art for art’s sake, with art on one side and life on the other, we can rest on this feeble and lazy idea only as long as the life outside endures. But there are too many signs that everything that used to sustain our lives no longer does so, that we are all mad, desperate, and sick. And I call for us to react.”[1] Antonin Artaud spent the duration of the Second World War, the duration of the German occupation of France, in an asylum; some of those years were spent in the German occupied zone, his madness surrounded by the world going mad. He went to Ireland to bring on the apocalypse, and instead he found this catastrophe: “The tortured man has been taken for a Madman by everybody. He has appeared before the world as a Madman. And the image of the world’s madness was incarnated in tortured man”[2]

France during the German Occupation

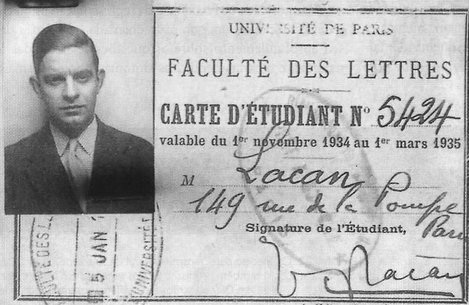

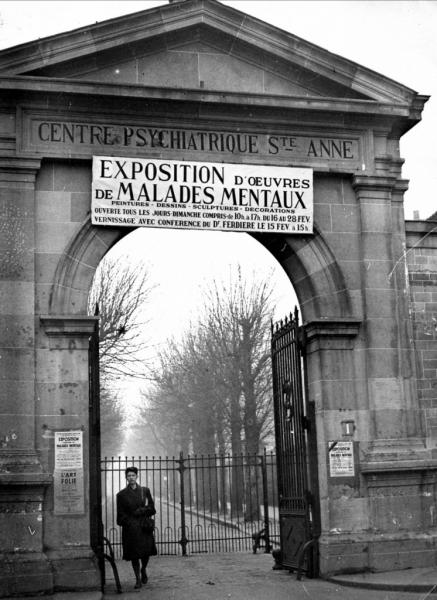

For the first few months, his family had trouble locating him. When his mother finally found where he was being held, she suggested he transfer closer to Paris, and he was moved to Saint-Anne’s asylum. This is where Artaud met Jacques Lacan, who famously said that Artaud, “is obsessed, he will live for eighty years without writing a single sentence, he is obsessed.”[3] The feeling was mutually negative. In “Van Gogh: Suicided by Society,” Artaud declares: “I have only to show you yourself, Dr. L…, as evidence, you carry the stigma [of erotomania] on your face, you vile swine.”[4] Lacan said that Artaud was incurable and his next institution, Ville-Évrard, had difficulty in diagnosing and treating Artaud because they transferred him, “without motive or reason from the maniacs’ ward (the 6th) to the epileptics’ ward (the 4th), from the epileptics’ ward to the cripples’ ward (the 2nd), and from the cripples’ ward to the undesirable’s ward (the 10th).”[5]

Jacques Lacan's Student ID, 1934-35

To make matters worse, Ville-Évrard was in the occupied zone, which meant that the patients had insufficient rations. Stephen Barber points out that “in each of the final two years of Nazi Occupation, nearly half of the asylum’s inmates died” from starvation and related complications.[6] Sylvère Lotringer explains that more generally that there were not many other treatments available at the time, and “no psychiatric pharmaceuticals available” so “psychiatrists simply let their patients waste away in overpopulated psychiatric units. The incurable ones were referred to as ‘asylum rot.’”[7] Robert Desnos heard of Artaud’s institutionalization at Ville-Évrard and knew the conditions in the German occupied zone were life-threatening. Desnos petitioned a doctor friend, Gaston Ferdière, to get Artaud over the occupation line and into Ferdière’s hospital. After administrative problems cropped up with moving Artaud to the Rodez asylum because it was in the free zone, Ferdière "hit upon a solution: Desnos and Artaud’s family would ask for his transfer to another institution within the German zone of occupation, but very near the demarcation line, the ‘rural’ mental asylum at Chézal-Benoît, of which Ferdière had previously been the medical director, and where he still had friends willing to help him. From there it would be easier to move Artaud across the demarcation line."[8]

Artaud had not been writing much more than letters since his initial institutionalization, but at the Rodez asylum he began writing and drawing extensively. This was, in part, because of Gaston Ferdière’s experimental practices. Ferdière was a poet and had been associated with the Surrealists for a time. One can assume Ferdière knew of Artaud through their friends in common.[9] His prescription included art therapy and electroshock therapy. Sylvère Lotringer argues that, in light of the available treatments, “the administration of electroshock therapy at Rodez was not so much a punishment as it was an early, groping attempt to modify a patient’s psychic condition.”[10] Still, Artaud abhorred it and publicly attacked Ferdière once he was released. Ferdière defended his decision in an interview with Lotringer, saying, “Anyway, I couldn’t have done Artaud any harm. And in fact, he began working again; he remembered what poetry was. All the work that followed, including the admirable Van Gogh, would not have existed had I not done what I did.”[11]

Exposition of Works by the Mentally Ill, Conference with Dr. Ferdière

The early days of electroshock therapy were brutal. By sending high concentrations of electricity into the body, many patients experienced unwanted side effects including, in Artaud’s case, a crushed vertebrae from violent convulsions. Given the horrific accounts of Artaud’s electroshock therapy, it’s difficult to side with Ferdière’s assertion that the treatment was an untempered success, though Artaud did begin writing again. He also took up drawing and created remarkable images which you can see here, here, and here. Most importantly for the discussion here, Artaud translated a section of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. These last years of his life, in fact, were his most prolific. Within a few years he was well enough to be released, and he passed the rest of his days—until 1948—just outside of Paris in an assisted facility.

1. Antonin Artaud, “No More Masterpieces,” translated by Mary Caroline Richards, The Theater and Its Double (New York: Grove Press, 1958), 77.

2. Antonin Artaud qtd. in Martin Esslin, Antonin Artaud, (New York: Penguin Modern Masters, 1976), 48-49.

3. Jacques Lacan qtd. David L. Goldman, “Theatre and Anti-Theatre of the Mouth, Part Two: Psychotic Glossolalia,” Canadian Journal of Psychoanalysis (2012) 20, 85-113.

4. translation mine. Antonin Artaud, Van Gogh Le Suicidé de La Société, (Paris: Gallimard, 2001), 28-29. Original text: “Je n’ai qu’à vous montrer vous-même, Dr. L…, comme élément, vous en portez sur votre gueule le stigmate, bougre d’ignoble saligaud.”

5. Stephen Barber, The Anatomy of Cruelty: Antonin Artaud: Life and Works, (np: Sun Vision Press, 2013,) 100.

6. Stephen Barber, The Anatomy of Cruelty, 102.

7. Sylvère Lotringer, “Who Is Dr. Ferdière?” translated by Joanna Spinks, Mad Like Artaud, (Minneapolis: Univocal, 2003), 130.

8. Martin Esslin, Antonin Artaud, (New York: Penguin Modern Masters, 1976), 54.

9. In his defense of his practices, Ferdière states that he knew Artaud had to be institutionalized initially and he understood why. “Certes depuis le début je savais qu’on avait dû l’interner et je savais pourquoi.” Gaston Ferdière, “J’ai soigné Antonin Artaud,” La Tour De Feu, Cahier 112, Decembre 1971, 26.

10. Sylvère Lotringer, “Who Is Dr. Ferdière?”, 130.

11. Sylvère Lotringer, “The Good Soul of Rodez,” translated by Joanna Spinks, Mad Like Artaud, (Minneapolis: Univocal, 2003), 176.

Language and its double