'A little slice of poetry turf'

Angel Hair archive, continued

Angel Hair was born in the “backseat of a car [as we were] driving from Bennington to New York,” Warsh says in his introductory essay to the Angel Hair feature in Jacket. Waldman and Warsh were driving with Georges Guy, a French professor at Bennington, and once they'd made the decision to publish Angel Hair, Guy offered them his and Kenneth Koch's translation of Pierre Reverdy's poem, “Fires Smouldering Under Winter.” The Reverdy poem begins the first issue, and the line, “Could it be enough to speak a word in this abyss,” perfectly captures the gesture of launching a literary magazine. Publishing Reverdy, translated by an older, more established poet like Koch, also lets the audience know from the start that Angel Hair is a serious rag.

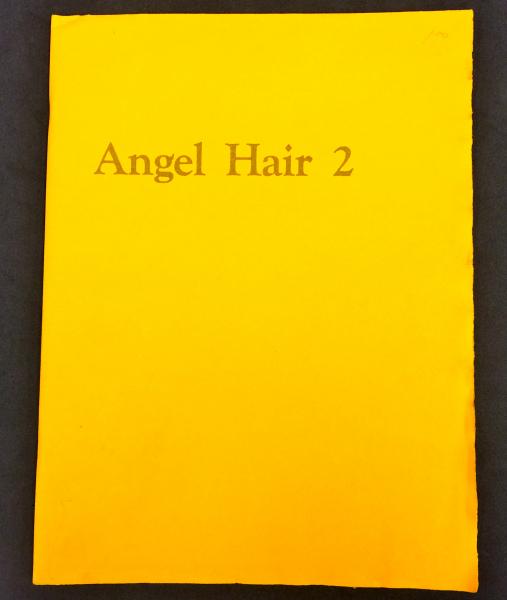

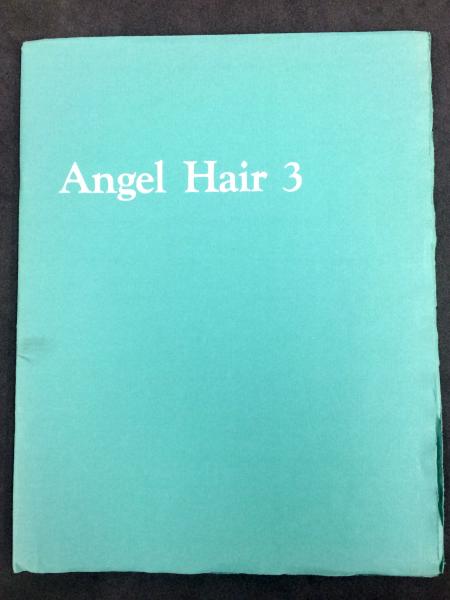

“By the time I moved back to New York City into 33 St. Mark’s Place the magazine had been launched,” Waldman writes in her introductory essay for Jacket. The first issue had cost them $150 to print. Bookstores complained about the journal's size, but Waldman and Warsh persisted with the 9 x 12 format. Waldman's job at The Poetry Project (which paid $6,000 per year) and Warsh's job at the Welfare Department would help subsidize the journal's production; meanwhile, their “skinny, floor-through ‘railroad’ apartment” became a gathering place for poets who attended readings at St. Mark’s.

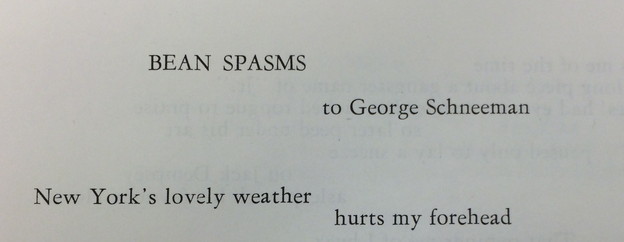

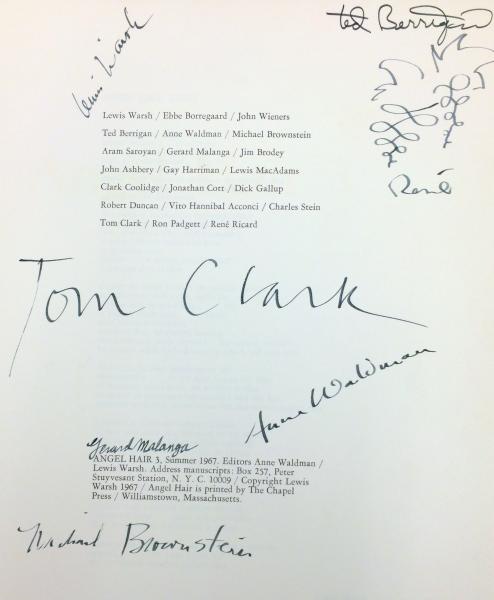

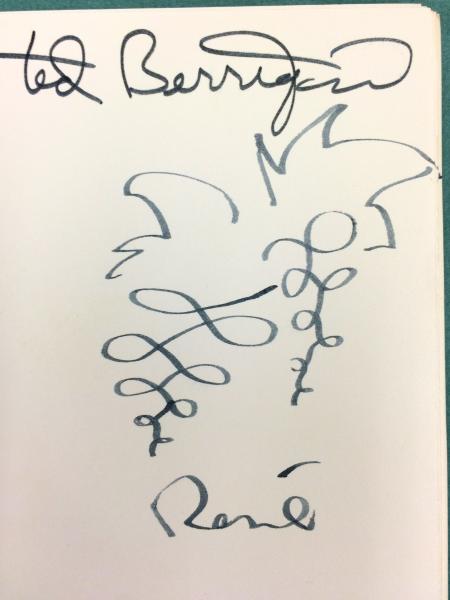

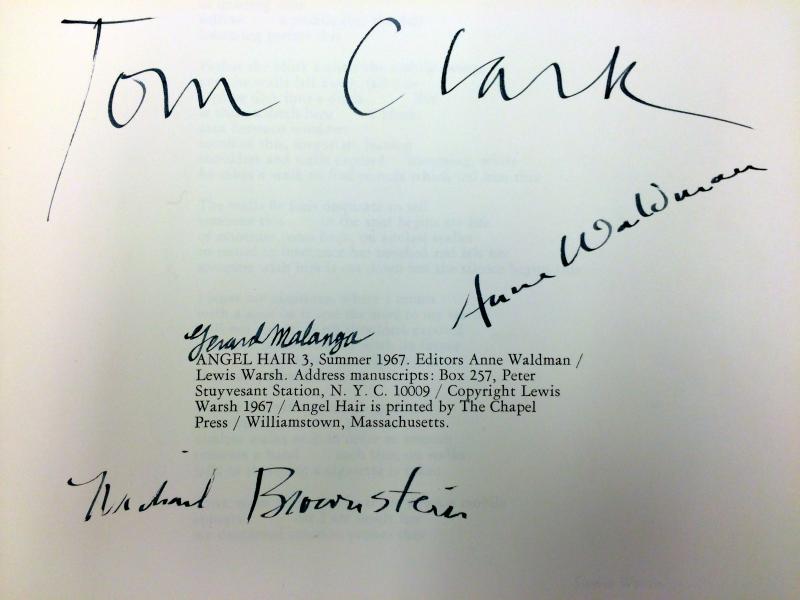

“By the time I moved back to New York City into 33 St. Mark’s Place the magazine had been launched,” Waldman writes in her introductory essay for Jacket. The first issue had cost them $150 to print. Bookstores complained about the journal's size, but Waldman and Warsh persisted with the 9 x 12 format. Waldman's job at The Poetry Project (which paid $6,000 per year) and Warsh's job at the Welfare Department would help subsidize the journal's production; meanwhile, their “skinny, floor-through ‘railroad’ apartment” became a gathering place for poets who attended readings at St. Mark’s.  “We spent hours smoking dope and listening to music and talking about poetry and writing poems together and gossiping about everyone who wasn't there and what jerks they were because they were missing out,” Warsh writes of hanging out with Dick Gallup and Ted Berrigan, two of the first regular visitors to their place. More poets and artists joined the list of frequent visitors--Michael Brownstein, Harris Schiff, Tom Clark, Peter and Linda Schjeldahl, George and Katie Schneeman, Gerard Malanga, Rene Ricard, Joanne Kyger, Jim Carroll, Bill Berkson, and others. Many of the visitors later (or concurrently) appeared in the pages of Angel Hair, and some of them later published books with Waldman and Warsh.

“We spent hours smoking dope and listening to music and talking about poetry and writing poems together and gossiping about everyone who wasn't there and what jerks they were because they were missing out,” Warsh writes of hanging out with Dick Gallup and Ted Berrigan, two of the first regular visitors to their place. More poets and artists joined the list of frequent visitors--Michael Brownstein, Harris Schiff, Tom Clark, Peter and Linda Schjeldahl, George and Katie Schneeman, Gerard Malanga, Rene Ricard, Joanne Kyger, Jim Carroll, Bill Berkson, and others. Many of the visitors later (or concurrently) appeared in the pages of Angel Hair, and some of them later published books with Waldman and Warsh.

This was a collaborative, community effort, though one in which, as Warsh notes, “there was almost no feminist or multicultural consciousness at work, no conscious attempt to balance the number of male and female poets contributing to the magazine, no thought of raising the political level beyond the politics of the poetry world itself.” This is instantly recognizable to the contemporary reader; I found myself flipping through the issues searching for women writers (Barbara Guest, Joanne Kyger, Denise Levertov, Anne Waldman, and a few others have work in Angel Hair) and writers of color (only Frank Lima, unless I'm mistaken). But also instantly recognizable to the contemporary reader is something both Warsh and Waldman discuss in their essays.  “We weren't thinking about career moves or artistic agendas. We weren't in the business of creating a literary mafia or codifying a poetics,” Waldman writes. “We talked about poetry constantly, wrote a lot, worked nonstop on the magazine and press...We created a world in which we were purveyors, guardians, impresarios of a little slice of poetry turf, making things, plugging in our youth, offering the gift of ourselves to help keep the ever-expanding literary scene a lively place.” Warsh notes that “no one I knew aspired to a tenure-track position, no one I knew attended MLA conferences, no one I knew had a PhD...no one was hustling in that direction.” And finally, back to Waldman, “It would seem in the new millenium poets have to hide their successes from one another. Envy, literary ‘politics,’ who's in, who's out--concerns seemingly tangential to the work itself cloud the atmosphere.” They worked jobs outside of the academy and savored the companionship of fellow poets and their own work outside of that other part of their lives--a way of life that more poets are returning to now, as academic jobs for many have become out of reach and/or incompatible with poetic life.

“We weren't thinking about career moves or artistic agendas. We weren't in the business of creating a literary mafia or codifying a poetics,” Waldman writes. “We talked about poetry constantly, wrote a lot, worked nonstop on the magazine and press...We created a world in which we were purveyors, guardians, impresarios of a little slice of poetry turf, making things, plugging in our youth, offering the gift of ourselves to help keep the ever-expanding literary scene a lively place.” Warsh notes that “no one I knew aspired to a tenure-track position, no one I knew attended MLA conferences, no one I knew had a PhD...no one was hustling in that direction.” And finally, back to Waldman, “It would seem in the new millenium poets have to hide their successes from one another. Envy, literary ‘politics,’ who's in, who's out--concerns seemingly tangential to the work itself cloud the atmosphere.” They worked jobs outside of the academy and savored the companionship of fellow poets and their own work outside of that other part of their lives--a way of life that more poets are returning to now, as academic jobs for many have become out of reach and/or incompatible with poetic life.

- Anne Waldman

- Barbara Guest

- Bill Berkson

- Denise Levertov

- Dick Gallup

- Frank Lima

- George Schneeman

- Georges Guy

- Gerard Malanga

- Harris Schiff

- Jim Carroll

- Joanne Kyger

- Kenneth Koch

- Lewis Warsh

- Michael Brownstein

- Peter Schjeldahl

- Pierre Reverdy

- Rene Ricard

- St. Mark's Poetry Project

- Ted Berrigan

- Tom Clark

Reports from the archives