On Kenneth Irby and 'Catalpa'

The most important books always got to me through the hands of a friend. I don’t know who put Ken Irby’s Catalpa into my grasp but I suspect Benjamin Friedlander. In the 1980s when we both lived in the Bay Area, Ben was generally out ahead in knowing who was writing the poetry we would need to look towards as we fashioned an emerging sense of our own practice. Many poets in my pantheon I owe to him giving me a book. The flat textured blue cover of Catalpa, with only a title and author’s name and a burnt-orange-colored medallion — half of it a flower or a half peyote button or some such design, done in the publisher Lee Chapman’s hand — looked handmade enough to make the book seem a cryptic discovery, but substantive enough to say, here’s a poet who has done some good, Projectivist work.

Catalpa opens with a dense “In Place of a Preface,” mostly quotes and dictionary definitions of land, landscape, plant, and place: four terms that have dawned with huge importance for a number of us who write what we loosely think of as an ecologically informed poetry. Equally salient in this little orienting note was citation of, and a thinking-through of, ideas from ecologist Edgar Anderson, geographer Carl Sauer, and poet Charles Olson. (I knew the work of all three from significant Turtle Island publications brought out by Bob Callahan.) Irby also cites Matsuo Bashō, Osip Mandelstam, and Jorge Luis Borges, so the book promises wide-open poetry culture spaces too.

Catalpa falls into three sections of poems, the first titled “Berkeley.” This section is site-specific to California Alta — the great north coast and rolling hills, the wide Central Valley, all the crackling vegetation of the region — with precise evocations of places that had come to sit deep in my own psyche. Point Reyes, Strawberry Canyon, Marysville, the Sacramento Valley. Recognizing what I now see as a bioregional approach, Ken’s “Berkeley” defines a cultural and natural area that stretches north to Oregon’s Willamette Valley and pokes over the crest of the Sierra Nevadas to the east. Historic personages rub against contemporaries in his pages — Sir Francis Drake, scout and mountain man Jedediah Smith, alongside friends named Eileen, Kelly, or Shao. Chinese ideograms occur on a few pages. Modern poets show up, some I knew something about, and some I’d not yet encountered. All this scholarship and care set into vivid street-smart lines:

The eye

circles and seeks

in the long map of California

a rest

along the Central Valley

looks down

keeping the corners out

I think this poem may have been the first time I ever saw a poet use the word watershed. History also came alive, in a way poetry had not done it for me previously. “Point Reyes Poem, 2” opens with Irby scratching a bad case of poison oak on his legs. That act leads back to Francis Drake and his British sailors, who call their California territory New Albion after they’d made landfall on the shores of Point Reyes, “past Limantour spit,” tromping the unfamiliar hillsides. In a distinct Irby gesture, the poem concludes:

what plants did Drake see growing here

that still grow here?

Turns out he and those other rough explorers came away blistering with the tarry plant (Toxicodendron) that every local knows to be careful of:

poison oak certainly

his men must have itched from

infernally, though Albion

we share across 400 years

the haze of fluid, sap

the blisters raised and lymph

on equal, heedless bodies

I’d never encountered something that made the local both comic and sacred like this, that provided my own summertime rashes of poison oak a four-hundred year backdrop. At the time I could most likely only say with awkwardness what I got out of Ken Irby’s lines, or what I hoped to emulate. But in the 1990s I would come across the term bioregion, and after that learn to stand by phrases like eco-zone, watershed, drainage system, plant community, and the like. This is the book, Catalpa — perhaps Lorine Niedecker’s poetry and Joanne Kyger’s were the other models — that showed how poetry can be made from the carefully investigated local.

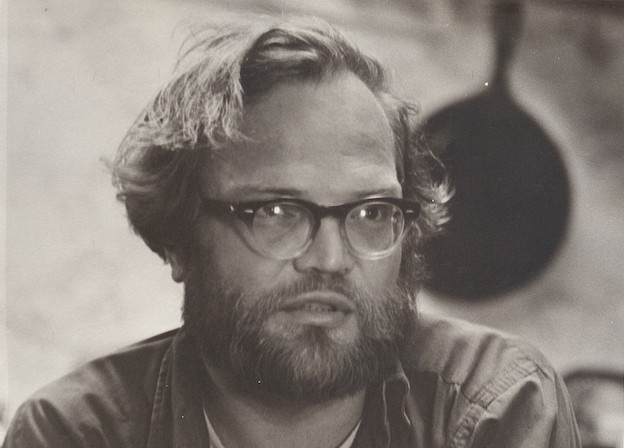

Sometime in the mid-eighties, not long after receiving Catalpa, I was asked to give a poetry reading with Ken Irby in San Francisco at Canessa Park, a former bank or insurance building down the street from City Lights bookshop and Brandi Ho’s Szechuan restaurant. What an honor. Ken and I struck up a friendship at the event. We began to exchange letters. I treasure the hoard of letters Ken wrote me: dense, tightly packed, rife with information on books, poets, music, botanical detail, Great Plains culture, medieval philosophy. Once when I moved briefly to another house, Ken wrote, “what plants do you see outside your window?”

My copy of Catalpa has a postcard from Ken, which I’ve used for a bookmark since 1988. It shows a Chinese bodhisattva sculpture — a famous one, of painted wood — from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Ken selected the icon to fit with my Sanskrit and Zen studies no doubt. Just to give a flavor of his intense correspondence I’m going to quote from the postcard. About halfway through, after various greetings and personal updates, he writes —

A glorious spring for flowering here, esp. trees, the various prunus, the redbud (Cercis canadensis — flowering Judas) — & now lilac, too, early & profuse (along with Verras of late — O Walt! & Duncan: What if — lilacs last in this dooryard bloomed?) — in (undecipherable) last weekend even my uncle’s tree peony, transplant from Mississippi, was in bloom — o Li Shang-yin! Very glad you’ve been in touch with Gerrit, who speaks well, warmly, of yr rich letters — I trust you will see him when you, he tells me, go to Boston, next month is it? He also spoke of a reading for you via Michael Franco at Tapas, where the Duncan Memorial was held — may all go well! Let me hear what you’ve heard of the SF RD reading — I’ve had no word yet —may all be green & lush & a-flower w/ you all! LOVE

Ken

Ken’s fountain pen hand is not too hard at first glance to read. But it turns out that its density and the pronounced flourishes and serifs make a great many words tough to decipher, slowing you down enormously. Typically his full letters would go a couple of tight single-space typewritten pages (in the very small font-size his typewriter had), then as he broke off to sign the letter he would add margin notes, then long looping addenda that wound around the pages; then he’d begin to write where the typewriter left off, and another page or two of his compact handwritten words would come. I used to think it would be a good idea to go through each letter and type out his handwritten material so when I wanted to reread the letters I could go quicker.

Letter writing is now a cryptic, all but vanished art. Ken was one of its great exemplars.

If you look at the above half-a-postcard you’ll see its density. It gives the names of three plants — (“dignify things by giving them their names” Joanne Kyger once told me). Ken dignifies one plant with three names: the popular, the Linnaean, and a vernacular. He also names five poets, two of them friends of ours; mentions a reading series; makes a riff on a Whitman line; and quite genuinely inquires about two memorials recently held for Robert Duncan — (pc. dated 21 April 1988, about three months after the older poet’s death). It all feels utterly human.

My daughter Althea had been born a week after Robert Duncan’s death. I remember when I wrote Ken of her birth and told Ken her name was Althea Rose, he alerted me to the Althea rosea, citing the stunningly complete horticultural dictionary Zukofsky had used for 80 Flowers — a set of books I wish I had the discipline to study. The althea is the common hollyhock, Ken said, with family connections to the mallow, the rose of Sharon, and many other mostly medicinal plants. (One Greek meaning of althea is healer.) Only Ken would have taken occasion to study up these facts and load a letter with his discoveries. Thanks to his efforts this became part of my family mythology.

These types of precise study are what Ken Irby has long represented to me, a comradeship in poetry that is based on passionate friendship, close reading of texts, and direct contact with the orders of nature, with babies, and with Islamic philosophers. The center of his poetry remains for me that first book I was given: Catalpa. What I needed at the time were poems I could check out with my own eyes.

Indian Summer in Berkeley means

the fogs come back in October

At the time I was reading everything I could from the early, indigenous poetry of California, and found in Ken’s book material that might have been reworked from the notebooks of Alfred Kroeber or Jaime de Angulo. Possibly Ken received much of his work in a vision.

My head rolls on the rim of the world

My eyes are not what I see with

In the basket, in the valley

In the creek bed under the water

October 2011

Edited byWilliam J. Harris Kyle Waugh